Guest contribution from John Crotty.

Spike Island had enjoyed a sleepy existence for most of its 1100 occupied years prior to the 18th century. A monastery founded in 635AD sought to enjoy the peace and isolation the location offered, its monks keen to blend with the harbor’s harmony. The rare arrival of marauding Vikings troubled their days but overall, the island offered an ideal location to commune closer with their one true God. These ocean incursions heralded the future use of the island location, and that of surrounding Cork Harbour.

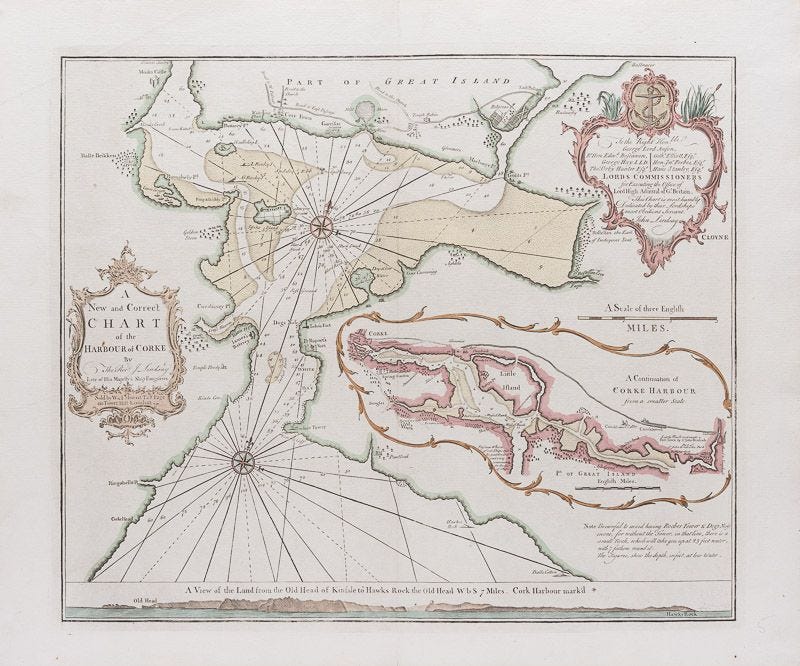

The island became a prison in the 1600’s to hold criminals or P.O.W’s prior to their Transportation, this the first of 4 prisons to arrive over the next 400 years. Its occupants were the defeated enemies of Oliver Cromwell who were bound for the Caribbean, starting a two-century association with the practice. This early use demonstrated Cork harbor’s suitability as a departure point for Atlantic voyages, journeys which increased in frequency with every century following the exploits of Christopher Columbus in 1492. The location began to replace nearby Kinsale as the primary provision and departure point for Atlantic crossings in Ireland from the early 18th century.

The necessity for a larger port was the endless increase in size and scale of the British Navy. Ocean going vessels and war ships became enormous, the largest man o’ war boasting a crew in excess of 800. Cork Harbour being one of the largest natural harbours in the world meant entire fleets could be safely docked from Atlantic storms, while the surrounding countryside estates in Cork and Waterford produced ample stores for replenishment. The location was about to see investment and fortification on a scale never before seen in Ireland, nor would it ever be surpassed.

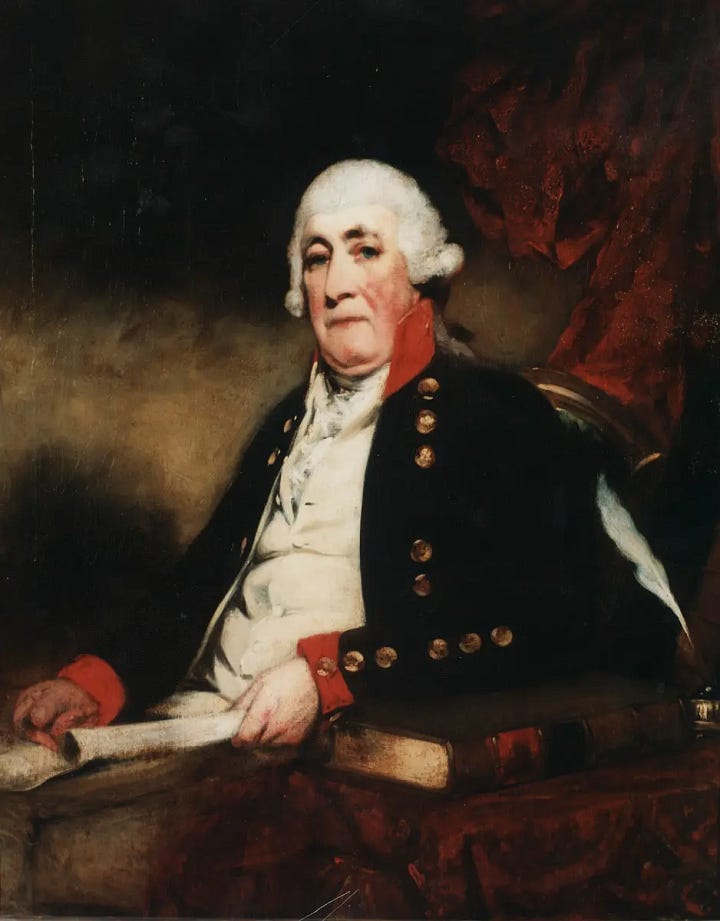

By 1778 Britain was engaged in the American Revolutionary Wars which were not going well. The involvement of France brought the fighting closer to home as Britain feared a mainland invasion. Several forts were constructed or reinforced around the harbour in the late 18th century, including modern day Forts Camden and Carlisle at the harbour entrance and Cobh fort on Great Island. It was on the central harbour location of Spike Island that defensive designer General Charles Vallancey eventually decided was the place to make a stand.

Fears of invasion weren’t helped when the marauding American Sea Captain, John Paul Jones, carried out attacks on British ports Whitehaven and Carrickfergus from a French base. Although minor and ineffectual, the raids hit home the modern realities of ocean-going warfare. The New World did not seem so distant and remote when American vessels were burning British harbors. Long standing calls for reinforcement of coastal defenses were urgently reconsidered, and Spike Island saw rapid and truly monumental change.

Efforts were modest at first, a lease negotiated with local farmer Nicholas Fitton to allow for 18 cannons to be installed after they were secured from Cobh fort. These hasty solutions were of little comfort when news of a letter published in France arrived in 1781, suggesting there should be an attack on Cork Harbour owing to its strategic role in the American War. This was suggested by no less a figure than American founding father Benjamin Franklin, who was in France to push Americas interests. It did not materialize but paranoia now turned to panic. The end of the American War in 1783 brought little comfort to British military strategists who strongly felt the only way to have peace was to prepare for war.

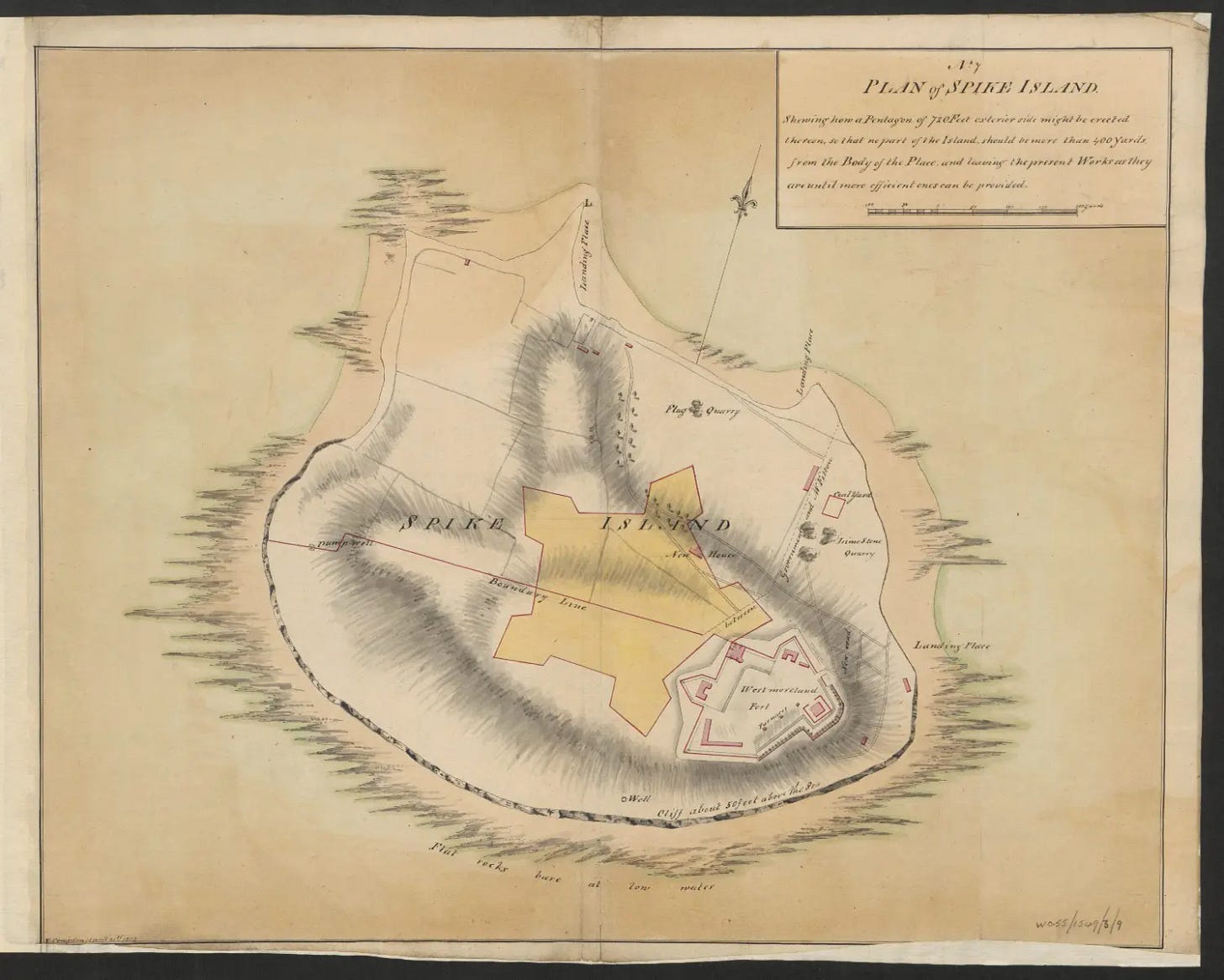

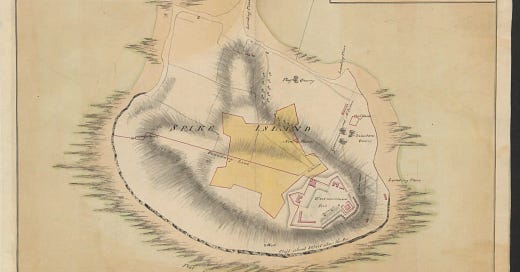

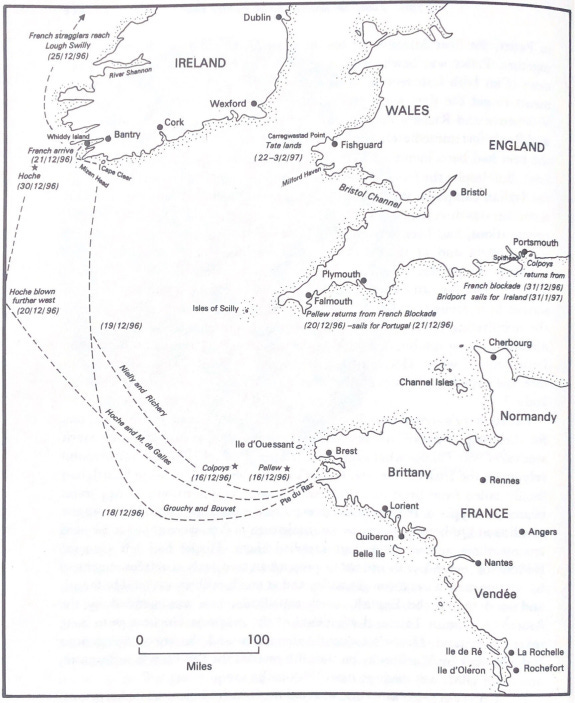

Funding arrived in 1790 for a not inconsiderable ten-acre fort, which was well on its way to construction by 1795 when Britain and France were at war once again. General Charles Vallancey, a veteran defensive engineer by this point who had trained on the impressive works of Gibraltar, saw his worst fear realized when an enormous French fleet departed for Ireland in 1796. Forty-three warships and 14,000 men sailed with the organizer of Expedition d’irlande, Wolfe Tone, aboard.

Vallancey must have feared the worst for his unfinished forts but something remarkable and unexpected happened. The fleet sailed right past the perfect landing spot for their enterprise, Cork Harbour, and on to Bantry Bay. Horrific weather conditions prevented any landing, with storms so severe the anchored ships were pushed back out to sea, their anchors dragging along the bottom.

The attempted invasion of Ireland was expected to meet the forces of the United Irishmen to overthrow British rule in Ireland. It failed miserably due to the weather and failure to land, as did the 1798 French effort which at least managed to land 2000 men in County Mayo. The United Irishmen rebellion of that same year was also a bloody failure. Which raises the question – why did the French fleets of 1796 and 1798 avoid the perfect landing point opportunity that existed in Cork Harbour?

The episode demonstrates the importance of good intelligence and espionage in advance of such undertakings. French spies roamed Ireland freely despite Britain’s best efforts to weed them out. They watched from the high hills of nearby Cobh as extensive works were undertaken at Spike Island and across the other harbour fortifications. Their report back to their commanders in France was it was best to avoid the fortified location, despite its landing suitability. Instead France would land troops up the coast at Bantry, who would fight their way to nearby Ringaskiddy and pound Spike Islands fort with mortars from the mainland.

French intelligence was off by some way, Spike Island not yet fitted out with the desired array of defensive cannons and mortars. The other harbour forts were also incomplete, but from a distance the collection of fortifications presented a formidable array. Later French visitors to the location realized they had made a grave error of judgement. Had the Spike Island works not been so misjudged by French spies, Irish history might be very different today.

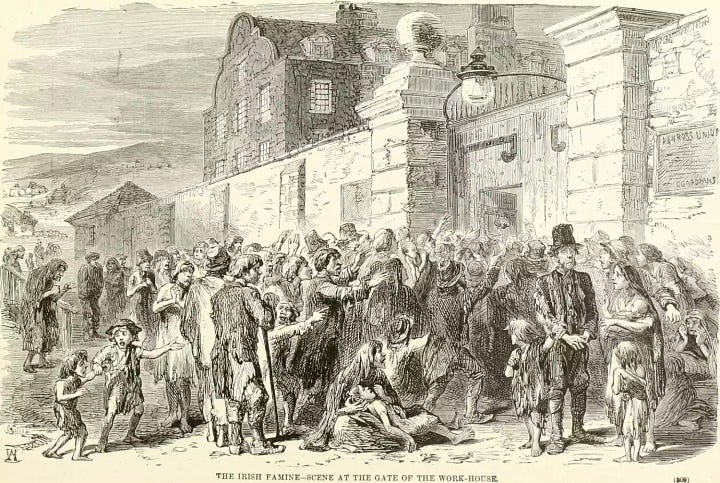

Britain undertook punitive measures against Irish nationals for the 1798 rising, reversing the many gains and relaxations of the Penal Laws in the 18th century. This culminated with the 1801 Act of Union which dissolved Dublin’s Parliament and absorbed it into Westminster, removing a great source of Irish pride and accomplishment. This action sowed the seeds for later discontent as first Daniel O’Connell then the Home Rule Party sought a repeal of the Union and re-establishment of a Dublin Parliament. The disconnect arguably reached its zenith with the Irish famine, when absentee landlords and government failed to appreciate, or be moved, by the suffering of those across the Irish Sea.

The lucky escape for Britain in 1796 was not missed by General Vallancey. He lobbied again for the funds needed to create the kind of fortification that would make even Empires tremble. By this point France’s population outnumbered Britain’s 3 to 1 and Napoleon was all conquering, meaning arguments against such necessary precautions were weak. The fort that began construction in 1804, largely because of Vallancey’s long lobbying, was so monumental in its scale it has never been surpassed in British or Irish history. At 24 acres it could fit two modern sports stadiums like Wembley Stadium and Croke Park within its walls. The Roman Colosseum, a wonder of the old world, would fit inside its walls four times over.

Extraordinary efforts were undertaken, like shaving the top off the entire island to set the fort down and out of sight of cannon fire from ships. Two million bricks made up the first order of materials, soon exhausting local supplies leading to shipments directly from London. Many more would follow as Britain flexed its muscle and spent its empire gains. Over one million pounds, around half a billion in modern terms, was spent in the first seven years. When the following four decades of additions are refinements are considered, the project is a multi-billion Euro construction that may well be the most expensive works in Irish history. The result is a fortress that will stand for a thousand years, testament to the great age of sail ships, military might and imperial expansion.

The fort would never be fully armed or considered complete, despite decades of work and investment. The end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 saw funding dry up as a population heavily taxed and devoid of many fathers and sons demanded change. The fort returned to quieter times the residents of the island village, which was populated by the families of the serving soldiers, watching as prison ships sailed out of the bay and emigrant ships departed for Australia and America. Cobh became the largest departure point from Ireland for well over a century, some 2.5 million seeing Spike Island from the deck as they sailed to a new life.

Convict labour arrived en masse in the 1840’s as a famine era prison opened. Like the fortress this quickly became a monumental endeavor, its population growing until it was the largest known prison in the world by 1853. 2400 inmates crammed the forts interior, every building brought into use and hasty additions like a timber prison and iron prison filled to capacity. It is still the largest ever formal prison in Britain or Ireland, its inhabitants including Fenians and men like William Smith O’Brien and Thomas Francis Meagher, the leaders of the 1848 rebellion. The island developed an association with Irish nationalism to add to its many historical strands.

The fort returned to military use from 1883 and was operational during World War One, training troops on the outer island in purpose built training trenches, replicas of those on the fronts of France. It also maintained a submarine net from its shore to the mainland. A third prison arrived in 1921 to hold Ireland’s War of Independence prisoners, a dramatic eight months beset by riots, escapes and a prisoner shooting.

The island became a political football in 1922 as Winston Churchill insisted it be retained by Britain in the Anglo-Irish Treaty, a small matter compared to the loss of the six counties of Norther Ireland. Its eventual return and handover to the Irish Defense Forces in 1938 came just in time to spare the fort from German bombers in World War Two. This set the scene for 40 years of Irish army and navy use before a final prison opened from 1985 – 2004.

This return to Ireland in 1938 and preservation from the horrors of World War Two mean Spike Island is now home to a perfectly preserved example of a star shape fortress from the late 18th century, one which is the pinnacle of 3 centuries of coastal defensive refinement. When combined with the impressive underground works at Fort Camden and gunpowder factory and trail that weaved its way from Ballincollig to Rocky Island, the Cork Harbour forts represent the finest examples in the world of military fortification undertaken in the late 18th – early 19th century.

There are talks, long overdue, of submission of the area for UNESCO recognition. Considering Spike Island’s long history as a monastery and island prison, the endeavor seems destined for success.

With no shortage of irony, a location that once imprisoned the Irish nation, and sought to forever incarcerate Ireland’s independence dreams, is now a source of great pride for Irish citizens. A symbol of Ireland’s inextinguishable desire for self-determination.

There is much of the world of the late 18th century to be seen and understood on Spike Island today, that of transportation, incarceration, emigration, the age of sail and empire driven military endeavor. Ireland’s historic island occupies a special, perhaps unrivaled place, in the Irish story.

Spike Island – the rebels, residents and crafty criminals of Ireland’s historic island, written by John Crotty and published by Merrion Press, is out now.

AUTHOR:

John Crotty is an Irish author from Cappoquin, County Waterford. A frequent traveller, John has been across the globe seeing over sixty countries including many of the worlds wonders. John has dedicated his life to understanding and sharing the history of the worlds many varied cultures, to better understand the Irish story.

John returned to Ireland to manage Irish wonder, Spike Island, as CEO for six years. John’s bestselling title, ‘Spike Island’, is the authors first book with further works on Irish history commissioned and commenced for release in 2025.

(See more info and pics at About - John Crotty - author (johncrottyauthor.com)

Below is a series of articles I’ve written here before on topics which were mentioned in todays post!

John I look forward to reading your book .