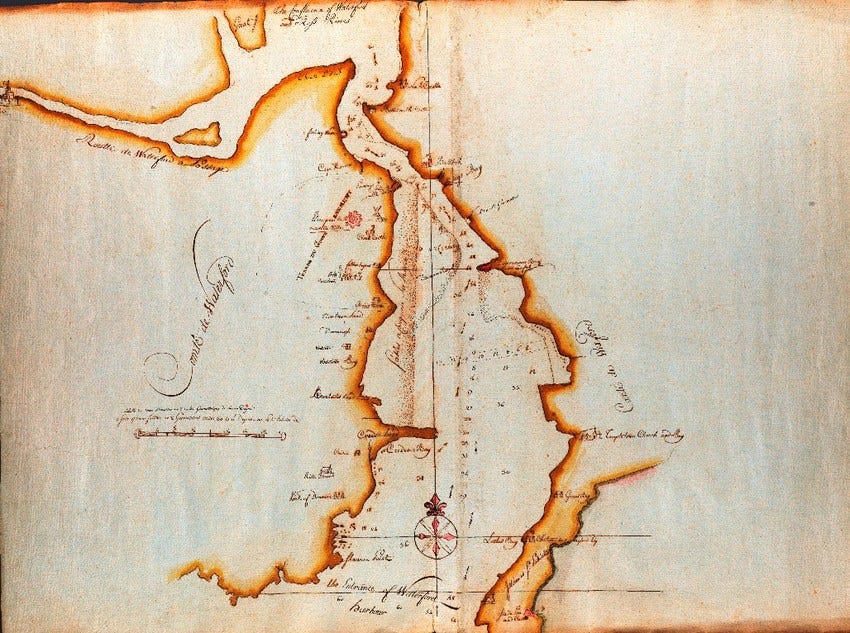

Passage East was and remains a fishing village in the Southeast of Ireland in county Waterford. It was very nearly a different town altogether, at one point, being the setting for ambitious plans for the resettlement of political refugees. On 4 April 1783 it was announced that an agreement was met by which the village of Passage East was chosen as the site of relocation for disaffected political refugees from the failed Genevan Revolution in 1782 – it was to be renamed New Geneva.

The Genevan Revolution is perhaps one that does not ring a bell to some. Whenever we consider the Age of Revolution, certain events and individuals come to mind for many – the American War of Independence, the French Revolution and Napoleon to name but a few. But amidst these, there was the Genevan Revolution of 1782, what some consider to be Europe’s entrance into the Age of Revolutions. The outcome shares a particular link to Ireland and Great Britain, and tells of an intriguing story of what could have been.

In the early 1780s Great Britain was in a position of acute vulnerability, with the American wars coming to a close, Britain on the beleaguered losing side. Closer to home in Ireland, strong political movements for reform gathered pace. In 1778 local militias were formed locally in Ireland to preserve law and order while troops were shipped to the Americas. These Volunteer Groups took advantage of the situation and became politically active, seeking stronger authority to rule their own affairs in Dublin. The direct result of this was increased autonomy for the Dublin Government through the repeal of Ponying’s Law, granting it powers to legislate for itself in many respects.

Accompanying this autonomy was the removal of significant blocks on Irish trade and imports, subsequently spawning a gratuitous amount of ambitious and ostentatious plans for economic revitalisation under Dublin’s newfound autonomy. One such plan was the resettling of disaffected Swiss reformers, mainly artisans and clockmakers.

What were some of the primary motivations for this project? Well, it is important to note that New Geneva was not the first plan of its kind. For the eyes of some, this simply served as a more modern attempt of previous protestant plantations of Ireland – the end goal being the conversion of the local peasantry to a more established, protestant way of life:

‘Making Ireland British through colonisation and plantation was expected to turn a barbarous and rebellious catholic society more loyal, industrious and peaceable’.

In April 1783 plans began to be put in place for the establishment of the town, and a sum of £50,000 was offered to the Genevans by the government to be used for the establishment of a colony of 1,000 watchmakers who were:

‘to have a charter of incorporation, by which they will be enabled to elect their own magistrates and to regulate entirely their own internal police’.

Generous offers of land were made to the Genevans by the Duke of Leinster of two thousand acres just ‘two miles from Athy and Castle Dermot, and six miles from Carlow’.

Another offer came in from Lord Ely, offering settlement on his estate in the county of Wexford ‘where it shall be my constant study to make your people a more rich, free and happy colony’.

None of these offers were accepted, however. Instead, New Geneva was to be located on the site of Passage East, a small fishing village in Waterford. The location chosen for the Genevans was no mistake. They were placed on a plot of government owned land in the heart of an area affected by the White Boys, a militant secret agrarian society prominent throughout southern Leinster and Munster. The expectation of the British government was that placing protestant republicans in the South in a heartland of catholic dissent would work to ‘make an essential reform in the religion, industry and manners of the south’.

A more profound reason for the Genevans seeking out a deal to resettle in Ireland was that they anticipated radical political and economic reform in Britain. They expected that they would be able to provide assistance and play a vital role in this reform as it were to happen. Ireland was also seen as an ideal location as it was in essence a ‘new’ state. Its ability to legislate was novel, its laws liberal and few – in the eyes of many reformers Ireland possessed room for growth and a lack of existing corruption the likes of which many saw rooted in British politics.

New Geneva, despite the early support from Britain and Ireland failed to take root for an array of reasons. The one which stands out most profoundly is perhaps the differing motivations behind such a project. I have already pointed out some of the British Governments motivations – to raise the Irish peasantry out of ‘a barbarous and rebellious catholic society’.

The Genevans however felt differently about the role in which the local lower classes would play in the evolution of any colony:

‘We must not overlook the need to conciliate the poor, who cultivate the soil that is offered to us’,

To the Genevan reformers, every order of society had its role to play and must be respected for the utility of their craft.

In thinking in such a way, many Genevan reformers managed to discourage their British benefactors by highlighting the role they played in Irish history, in perpetuating conditions which created the Catholic peasantry and kept them impoverished:

‘the greed and harshness of the great landowners have made the tenants violent and irritable. That is the reason for the disorders of which you have heard. They are in revolt against treachery and abominable outrage. If we behave well, we shall gain their confidence’.

Naturally this did not help in garnering support for their cause. Alongside this, the Genevans’ understanding of the settlement and the rights owed them after moving did not align with that of the British government. The Genevans chaffed at the restrictive voting rights which existed, and the local landowners were remiss to make exceptions.

This was all compounded, on the British and Irish side, with the thought of entrusting exiled reformers to establish a town at such a strategic location – right across the river from Duncannon Fort, in the event of war or Invasion, could they be trusted to play their part in a defence?

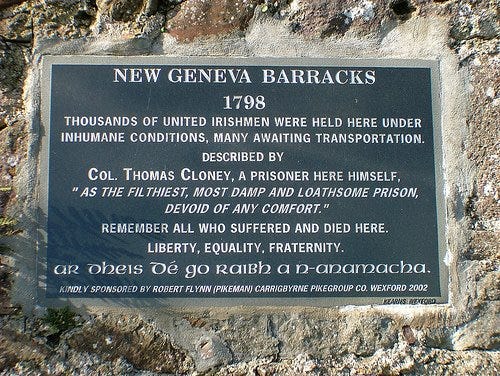

The foundation stone for the town was laid in July 1784 – upon it was inscribed the date and the reason for this settlement. And just 6 weeks later all plans of resettlement were dropped, and New Geneva was but a failed project. There were only a handful of buildings completed and the site was subsequently converted to a military barracks shortly after.

Ironically, the site chosen for New Geneva and the remains of what was built to be an example to Ireland of the triumph of freedom and democracy, became a prison for Irish patriots in 1798 when a rebellion broke out. It garnered a reputation for the brutality shown to prisoners and the methods used to extract information.

One can’t help but ask, what if? What if the settlement was successful and the colony was allowed to flourish with its own internal administration. What impact would they have had on the political landscape in Ireland. What role could they have played in the establishment of reform movements in the 1790s such as the Society for United Irishmen. How might their influence have affected the radicalisation of political groups and the subsequent rebellion of 1798. This to me is one of the great things about history, it poses many questions, some of which we will never know the answer to and out of it comes a universe of imagination based upon very real possibilities had history simply taken an alternative path.

Further Reading:

Richard Whatmore, Against War and Empire: Geneva, Britain, and France in the Eighteenth Century (Yale, 2012).

Richard Whatmore, ‘Saving Republics by Moving Republicans: Britain, Ireland and ‘New Geneva’ During the Age of Revolutions’ in History (London) (2017), vol. 102, no. 351.

Isadore Ryan, ‘Republicans seeking asylum’ in History Ireland (2018), vol. 26, no. 2, online at: https://www.historyireland.com/republicans-seeking-asylum/