l’Expédition d’Irlande, December 1796: The Greatest 'What if?' of the Revolutionary Era for Ireland, perhaps even Europe itself?

The French Expedition to Ireland under Lazare Hoche, December 1796.

Every so often it is fun, as a historian to indulge in the fantasies of alternative versions of events. The ‘What ifs’ of history are incredibly fascinating to theorise, particularly when so many major events have been uprooted at the final hurdle by unlikely and unexpected events. I firstly want to thank Dr. Ciarán McDonnell, it was a podcast with the Napoleonic Quarterly he did in the past year and a recent post on twitter which inspired me to write about this episode of Irish history. He’s a fantastic historian who focuses on Irish 18th and 19th century military, political and cultural history.

The greatest what if for me, and many Irish historians of the Age of Revolutions is the failed French expedition to Ireland in 1796. On 16th December a fleet sailed from Brest in north-western France carrying 14,450 troops in all. Some would have you believe that something magnificent would have occurred if this all went according to plan. The French would have been welcomed with open arms and a sister republic would have been established, severely weakening the position of Britain as an enemy of France.

In reality however, this is unlikely to have happened - despite the desires of the United Irishmen and their attempts to paint a far more rebellious picture of Irish society at the time. Rather what is more likely to have occurred is a deep rooted, violent and regretful civil war on the island of Ireland. In the minds of French leaders such as Lazare Hoche - the Irish Expedition was to be a mission of vengeance. It was to be a response to the years long civil war in the Vendée, supported in earnest by the British government.

The Wars of the Vendée were a counter-revolutionary uprising in the west of France which consumed much of the revolutionary governments domestic affairs in the 1790s. It broke out first in March 1793 and did not end until July 1796. When we consider the French Revolution in popular imagination - what comes to mind are the guillotines in Paris under the Terror of Robespierre. Those killed in Paris, appear miniscule in comparison to the level of violence witnessed in the Vendée though. During the reign of Terror, in the winter of 1793-4 the Republican forces shot, drowned or guillotined c. 15,000 people in the cities and a further c. 20,000 in the country side. By the end of the conflict roughly 20-25% of the regions population had been killed - estimates suggest 200,000 in total.

In late 1794 Lazare Hoche was given command of troops in the north-western region of France and tasked with suppressing the revolt for good. For two years he commanded republican forces in the region and was instrumental in bringing and end to the royalist revolt. Hoche was later awarded the command on the Irish expedition following his success and he endeavoured to make it a mission of retribution. The Irish expedition was to be for Britain what the Vendée was for France.

The expedition was to launch in late October which would’ve facilitated better weather for the journey and landing. After the end of the War in the Vendee and peace with Bourbon Spain a significant force was freed up for the operation and the Atlantic fleet was given to Hoche to be used as he saw fit.

The project immediately hit speed bumps and was ultimately stalled for months - failing to launch until mid-December into unpredictable and poor sea conditions. The fleet embarked on the 16th December in the midst of one of the worst winters reported in over a century. A study in History Ireland by John Tyrell showed that December 1796 had a full array of erratic weather conditions,

‘from almost summer-like calm, dry, sunny weather to the most severe storms and intensely cold, snowy weather’.

Upon the arrival of the French, Ireland found itself blanketed in a severe snow storm, one French member of the expedition noting:

‘Nothing in the world could have looked more sorry or desolate than the country which appeared before our eyes. It seemed uninhabited and we could see neither church towers, nor villages, nor any trace whatsoever of cultivation or of population’.

The French coast had been under a constant blockade during the Revolutionary Wars which forced Hoche to act brash and against his better judgement. He ordered the fleet to move out quickly and take a riskier route around the Point de Raz where a ship carrying 1500 troops floundered on the rocks, killing c. 1,450 on board - a bad omen for things to come.

On the night of December 16th a thick fog subsequently descended over the fleet leading to confusion and causing it to disperse. It did also allow the French ships to slip through the British blockade undetected. As a result of the confusion, Hoche was separated from the bulk of his fleet for the remainder of the venture. His desire to keep details of the mission a secret was a hinderance on affairs as once the fleet became dispersed, his officers were none the wiser as to where the intended landing spot was to be.

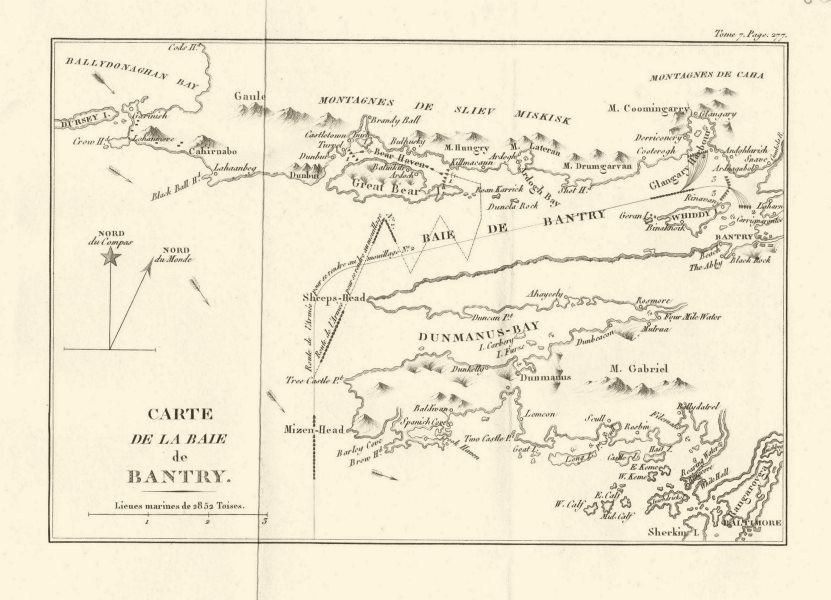

What followed was a strange affair - on 23rd December much of the French fleet lay off the coast of West Cork for days - making no moves to disembark and land on the shores. Waiting for the arrival of Hoche and his flagship before continuing. This proved incredibly frustrating for the United Irishman Theobald Wolfe Tone stuck aboard the Indomptable who at one point noted,

‘I am now so near the shore than I can in a manner touch the sides of Bantry Bay with my right and left hand: yet God knows whether I shall ever tread again on Irish ground’.

The desire for privacy on the part of Hoche was understandable in order to avoid information reaching the British and floundering any plans before they were set in motion. As Elliott points out though,

‘given the sudden change in all previous instructions [prior to departure], his failure to take precautions to ensure against confusion was careless’.

While it appears one of Hoche’s officers had been given a map of Bantry Bay to be opened upon arrival, it was accompanied by no instructions leaving the whole expedition in disarray until his arrival. His delay was compounded by counter winds resulting in his ship making little to no progress for days. It was not until 30th December that Hoche sighted the west coast of Ireland and learning of the departure of the rest of the fleet on 26th December, he sailed for home.

The expedition was a resolute failure for the French and Great Britain was saved again by the weather. This episode calls to mind the Spanish Armada in of 1588 - just like the Spanish, the French Armada was thwarted by stormy seas. It would be wrong however to deem it an accident of pure chance. The human element is ever present in Hoche’s leadership and his desire to maintain explicit secrecy among his officers. Had they known more of where they were to land and form a beach head, he may have arrived to an already disembarked force in Bantry Bay - ready to move on Cork city.

This not only embarrassed the French government but similarly embarrassed the British Navy. Many questions were asked of their ability to keep the French at bay. Somehow a significant military force slipped past their blockade and c. 15,000 troops were nearly planted in Ireland. From this point on coastal defences in Ireland were reinforced with redoubts and Martello Towers. There now stands an anchor from a French ship in Wolfe Tone Square in Bantry, found during a survey of the sea floor in 1981.

This expedition was the final major attempt to invade or reinforce Ireland in the fight against Britain. They would of course successfully land troops in the west of Ireland during the 1798 Rebellion but with significantly fewer numbers and largely after the Rebellion had already failed. It remains one of the greatest what ifs of history - not just for Ireland but perhaps for Europe. How would a British Vendée have affected appetites for continuous warfare against France? Would it have forced them to the negotiating table sooner? Or would it simply have encouraged a more resolute and vicious fight, turning Ireland into a region soaked in the blood of a bitter civil war?

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

Marianne Elliott, Wolfe Tone (2012)

Marianne Elliott, Partners in Revolution (1982)

J.G. Tyrrell, Weather & Warfare Bantry 1796 revisited - https://www.historyireland.com/weather-warfare-bantry-1796-revisited/

Michael Waldron and Orla-Peach Power, THE STORM OF DECEMBER 1796 - http://www.deepmapscork.ie/past-to-present/climate/storm-december-1796/