The 'ecravos brancos' of Rio de Janeiro, 1826-28.

Irish and German Mercenary Soldiers' revolt.

Following the Napoleonic Wars of 1799-1815, Europe entered into a period of peace not experienced in over twenty years. For many nations, this allowed for a time of reflection, economic recovery and evaluation of the wider geo-political climate. For Ireland, it largely spelled economic decline. During the wars Britain was largely cut off from the European continent economically due to Napoleons Continental system, which instituted a continent wide blockade against all British trade and applied to every country under French rule/influence - which ultimately was all but one, Portugal.

During this time, the United Kingdom became heavily dependent on Irelands agricultural resources to supply them with grain for the general public and to supply its armed forces with adequate supplies of food. With the end of the wars in 1815, this reliance was no longer necessary and the European market was open for trading once more, allowing more competitive prices to come up against Irish goods. Between 1815-21, grain prices in Ireland fell by half, while the population continued to increase rapidly. This would continue until the 1840’s while land holdings continued to get smaller as land use was altered to fit a changing market which required less field hands.

Such was the economic situation immediately prior to today’s topic. It’s another bizarre story that most, I’m sure will have never heard of. I want to talk to you about a small group of Waterford and Cork farmers who emigrated to Brazil in the 1820s to start a new life, one which was laid out to them by a charismatic Irish colonel, in the employ of the Imperial Army of Brazil - instead of the American Dream, they were offered the Brazilian Dream.

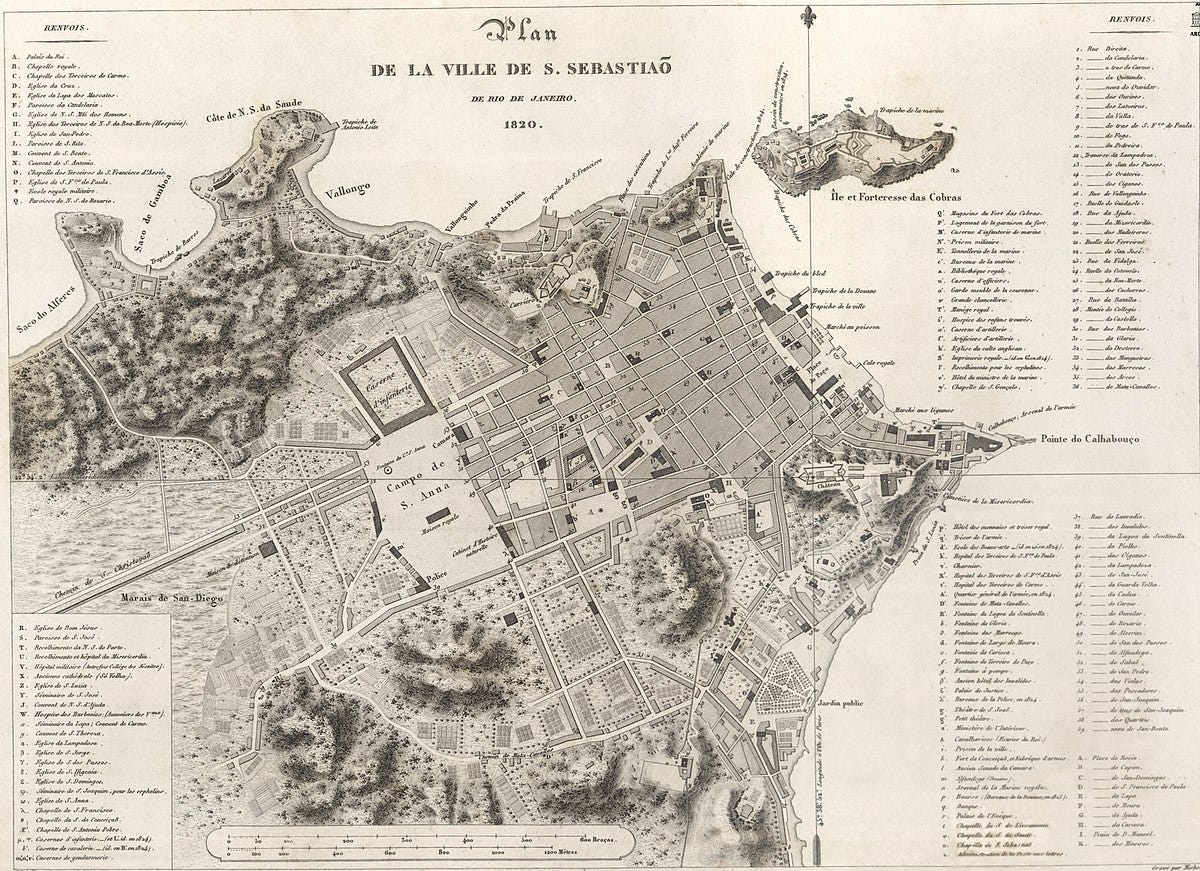

First let us start with some more context about Brazil during these years. During the Napoleonic Wars and more specifically Iberian campaign, in 1808 the royal court of Portugal fled to their colony in Brazil for their own safety where they managed state affairs for a number of years, and Rio de Janeiro became the unofficial Portuguese capital city. In 1815, the Portuguese crown prince Dom John, acting as regent, created the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves, which raised the status of Brazil from colony to kingdom.

In 1821 following the death of his mother Maria I of Portugal, Dom John ascended to the throne and returned to Portugal to rule from the city of Lisbon, the original capital of Portugal. He designated his son and heir, Dom Pedro as regent to the Kingdom of Brazil. Wanting to return to the status quo which existed prior to the Napoleonic Wars, the Portuguese government made efforts to limit and reduce the autonomy granted to Brazil since 1808 - ultimately their desire was to return it to more of a colonial possession, than a kingdom under their control. The issue is, when liberties and self governing authority is given to people, particular to an entire country, it is incredibly difficult to take those liberties away.

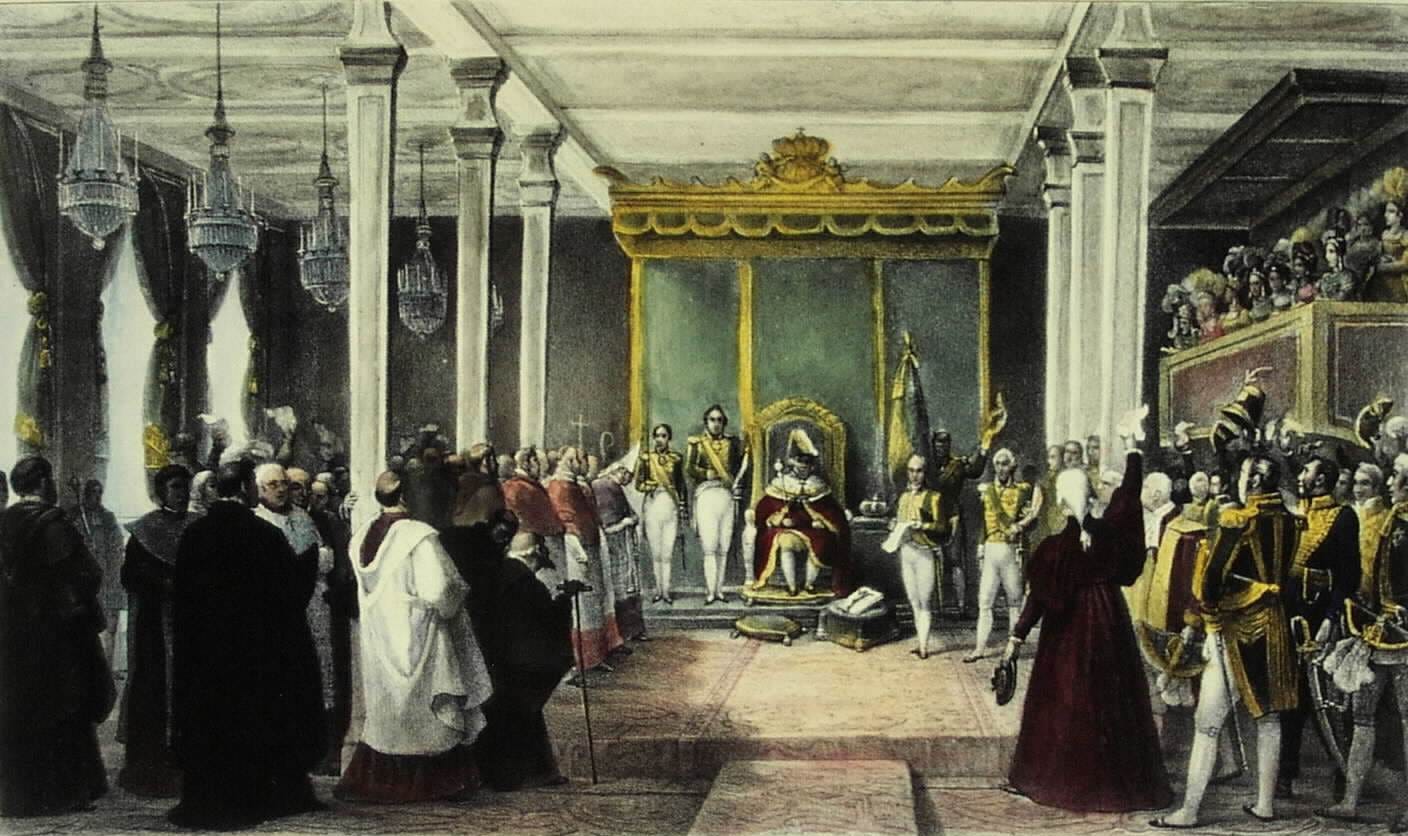

Pedro under the influence of influential Brazilian leaders and politicians was convinced to declare Brazilian Independence from Portugal in September of 1822 and a month later was acclaimed Pedro I, Emperor of the newly created Empire of Brazil, a constitutional monarchy. This move was opposed by many military groups throughout Brazil, regiments who were part of and loyal to the Portuguese crowns army. For two years violence engulfed the new Empire and in 1824 hostilities finally came to an end, with Portugal officially recognising the independent nation of Brazil in 1825.

Dom Pedro’s reign of Brazil was wrought with crises and difficulties ranging from provincial secession attempts, economic difficulties, balancing the needs of Portuguese and Brazilian interests and many more. One such difficulty surrounded his efforts to boost European migration to Brazil in the 1820s. He targeted two groups of people for this venture, German and Irish.

In the Northern and Western German states Georg Von Schäffer was tasked with recruiting German soldiers to fight in the Brazilian Army as well as colonists for colonial resettlement. He proved so effective that German governments banned further emigration to Brazil - he recruited 2,000 soldiers and 5,000 colonists. From this roadblock, Pedro shifted his gaze to Ireland. One Irish observer with the British Embassy in Rio, Robert Walsh, later commented that he decided on ‘the Irish, who from the redundancy of population at home, might easily be procured’.

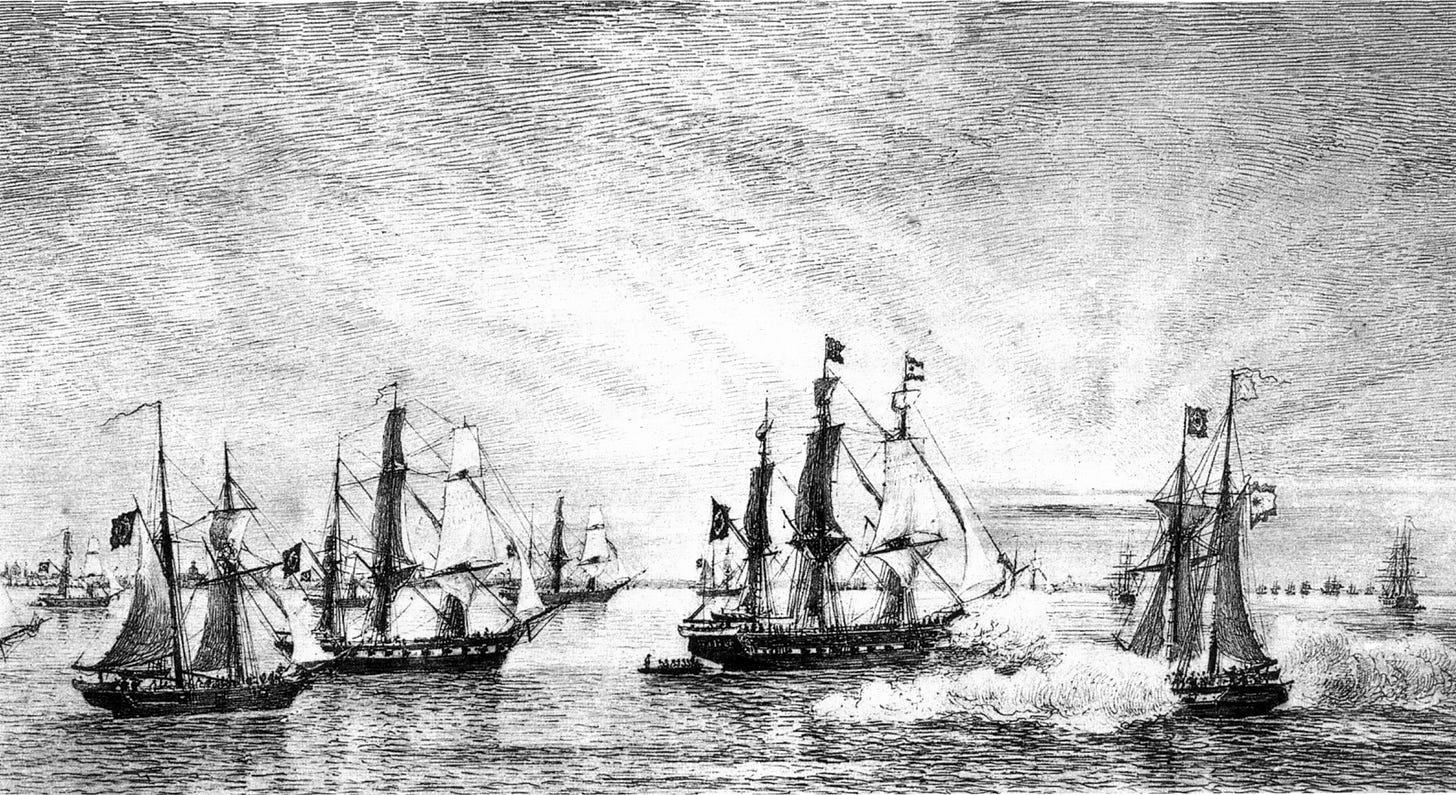

William Cotter, an Irish born colonel serving in the Brazilian army was dispatched to Cork in an effort to recruit as many soldiers as possible. He promised illiterate farmers from Cork and Waterford that if they emigrated they would earn more money and if they enlisted in the armed forces, after 5 years of service they would be given 50 acres of land to farm. Many grew hesitant at this last detail but agreed to join the local militias instead, for the same deal. According to Edmundo Murray in his article listed below, he was able to convince 2,450 men, 335 women, 123 young men and women and 230 children to make the voyage aboard 10 ships in the winter of 1827-28.

Upon arrival it became immediately clear that Cotter had made up much of his promises of land grants and good pay. There were attempts to press the men into military service and to be brought to the front lines of the ongoing conflict with Argentina. The Cisplatine War was fought in the 1820s between the Empire of Brazil and the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata over control of Brazil's Cisplatina province. It was fought in the aftermath of the United Provinces' and Brazil's independence from Spain and Portugal, respectively, and resulted in the independence of Cisplatina as the Oriental Republic of Uruguay.

Side Note: a number of other Irish figures play prominently in the recent history of Argentina and Chile on their paths to Independence (Ambrose and Bernardo O’Higgins). Also for Argentina, during the Cisplatine War, William Brown served in the Argentine forces and earned the moniker ‘Father of the Argentine Navy’.

The Irish arrivals made a plea to the British Ambassador resident in the Brazilian Capital, Robert Gordon. His persistent protests to Brazilian officials ensured a slight improvement in their conditions - most men were allowed to refuse service in the army and subsequently fewer than 400 joined up. There were plans to form an independent Irish brigade but lacking sufficient troops, they were amalgamated into the Third Battalion of Grenadiers, a unit formed from the previous German arrivals - men equally unhappy with their lot in their new home.

It must be noted that these ‘soldiers’ never made it to the front lines but instead served as garrison troops in the capital city where their conditions continued to be terrible. Many suffered and eventually died from diseases which spread easily in their cramped and unclean living conditions. Despite repeated requests for medical attention and medicine it fell to the doctors from the British Embassy, Dr’s Coates and Dixon, to come and take care of them with limited supplies, largely at their own expense.

If they didn’t have enough to deal with already, they also had to contest with the local black slave population or moleques. The moleques took advantage of seeing a social group poorer than them, taken advantage of and left to rot. Taunts of 'ecravos brancos' (white slaves) when the Irish first landed escalated into individual fights, then large scale brawls, and finally, into murders by roving bands on both sides in the streets after dark.

In the Spring of 1828, many of the Irish families were relocated to a town on the Atlantic coast called Salvador and from there they settled as labourers at Taperoa. Unfortunately for those enlisted in the army, conditions continued to worsen, unrest grew among both the Irish and the German mercenaries due to rough treatment, non-payment of wages, general misery and rumors of going into battle soon. The German contingent of of the Third Battalion of Grenadiers led a revolt against the government on 9th June 1828, and were joined by 70-80 enlisted Irish migrants. The battalion took to the streets of Rio de Janeiro where their ranks were swelled by Irish civilians and what took place was described by one official as ‘an orgy of destruction in the centre of Rio’.

In contemporary sources it is claimed that one of the German mercenaries had been sentenced to 50 lashes of the whip for a minor infraction, but it was later changed to 250. Before reaching the sentence number, German soldiers liberated the accused and fourteen mutinous German grenadiers left their barracks at Sao Cristovao to capture their hated Brazilian commander on the streets of Rio. The Brazilian major, tipped off to their approach, managed to barricade himself into a police station.

The mutineers were spotted by a party of up to eighty Irish soldiers and the two forces joined up and started rampaging through the streets of downtown Rio. Their ranks swelled by Irish and German civilians, the mob started looting shops and bars, burning houses and terrorising the indigenous poor people of Rio, the cariocas. The Irish mob included women and children, who, according to reports given shortly after the riots, helped to burn up to a hundred houses and businesses, killing or maiming many of the occupants.

It was clear to the local authorities that they had not the ability or the manpower to deal with such a significant rebel force in the confines of the city, with most of the local armed forces being deployed elsewhere for garrisoning or at the front lines of the war. In an act of desperation, officials began handing out weapons to the local populace in an effort to quell further destruction from the rioters.

After two days of rioting, the mutineers retreated to their barracks where they could mount a stronger defence in a constantly losing battle against the locals. By this time, several city blocks of Rio had been razed to the ground and hundreds of mutineers had been killed in street fighting and brawls.

At one point, the Emperor had requested the aid of British and French marines stationed just off the coast. When word reached the rebels that these professional troops were coming ashore, many rebels surrendered to the authorities. The final barracks was only re-captured after being stormed on the fourth day, bringing a series of chaotic days in the Brazilian capital to a close.

As a result of the involvement of some Irish soldiers and civilians in the riots on June 1828, the decision was made to send back all Irish migrants brought over by William Cotter. Of the roughly 2,500 Cork and Waterford residents who made the trip to Brazil under the false promises of William Cotter, only around 1,900 can be accounted for confidently. We know that 1,400 were sent back to Ireland, and as demanded by Robert Gordon, the Brazilian Court was forced to foot the bill for any expenses incurred. Approximately 150 migrants died in the rioting in those few days, and a final 400 remained in Brazil as farmers largely settling in the southern provinces of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul. This leaves around 600 Irish unaccounted for, we must sadly assume that they perished either on the journey to and from Brazil, or suffered and succumbed as a result of the poor conditions offered them upon their arrival.

Thus closes a rather eventful, chaotic and brief period of Irish history. For a short few months Irish farmers, emigrating to Brazil to start a new future for themselves, conned into enlisting in the Imperial army and treated terribly for their efforts. These migrants were tested so much, and were swayed by their German counterparts to the point of launching a riotous rebellion in the Brazilian capital. This would be one of many crises faced by the imperial government under Don Johns reign, and all because of the conniving charisma of William Cotter, a man who never re-enters the historical record, as far as can be discovered thus far.

Help Ireland and the Age of Revolution grow!

This newsletter is and always will be free to access, enjoy and engage with, but it does take time and effort to create alongside my usual work routine. If you enjoy what I do here and want to see it become even better, please do consider chipping in!

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

Joe O’Shea, Murder, Mutiny and Mayhem (2012)

Peter R. Mills, Hawaii's Russian adventure: a new look at old history (2002).

Nikolay Bolkhovitinov, ‘Adventures of Doctor Schäffer in Hawaii, 1815–1819’ Hawaiian Journal of History (1973), vol. 7 pp. 55–78.

Lee B Croft, Georg Anton Schaeffer: Shipping Germans to Brazil (2012).

Robert Walsh, Notices of Brazil in 1828 and 1829 (London, 1830), online at: https://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/item/id/518704.

Edmundo Murray, ‘William Cotter Irish officer in Dom Pedro's army of imperial Brazil’ in Irish Migration Studies in Latin America (2006), vol. 4, no. 3.

Fascinating. It reads rather like earlier accounts elsewhere of indentured servitude, only these Irish didn't know what they were getting into.

The Irish in Argentina is also worth exploring. On a recent trip to Argentina I came across “The Kavanagh Building” Estancia Cullen in Patagonia owned by Patricio O'Byrne, Rudolfo Walsh a disappeared journalist, and the receptionist in my hotel in Buenos Aires was called Patricio O’C????.