Last time we looked at the Attorney Generalship of Kerry born Michael Keane, who made a career as a colonial official in the Caribbean, mostly based on the Island of St. Vincent. This week we’ll look at another character entirely, that of John Black. Black, Belfast born slave owner and sometime slave trader spent much of his life on the Island of Trinidad, not as a colonial official, but rather as the type who spent his life evading colonial officials instead. While Keane was known for his diligence and ability to work across cultural and sectarian divides, and thus well respected – Black was known to have been a sinister figure: ‘impish, renowned for his meanness and admiringly feared for his crooked dealing’.

Belfast by the end of the 18th century had entered into an era of precipitous growth, it was coming to form a crucial link in the wider imperial Atlantic. Both it and the wider province of Ulster had become linked to the West Indies not just by merchants but by a ‘mobile Atlantic community of ship captains, agents, merchant factors and West Indian sojourners’. It’s links to this wider Atlantic world is what encourage and promoted such rapid development, it was the city which first published reports from America of the outbreak of hostilities in Lexington-Concord, it was the first stop on the way to Britain from across the long Atlantic voyage, it was the last stop from England before North America.

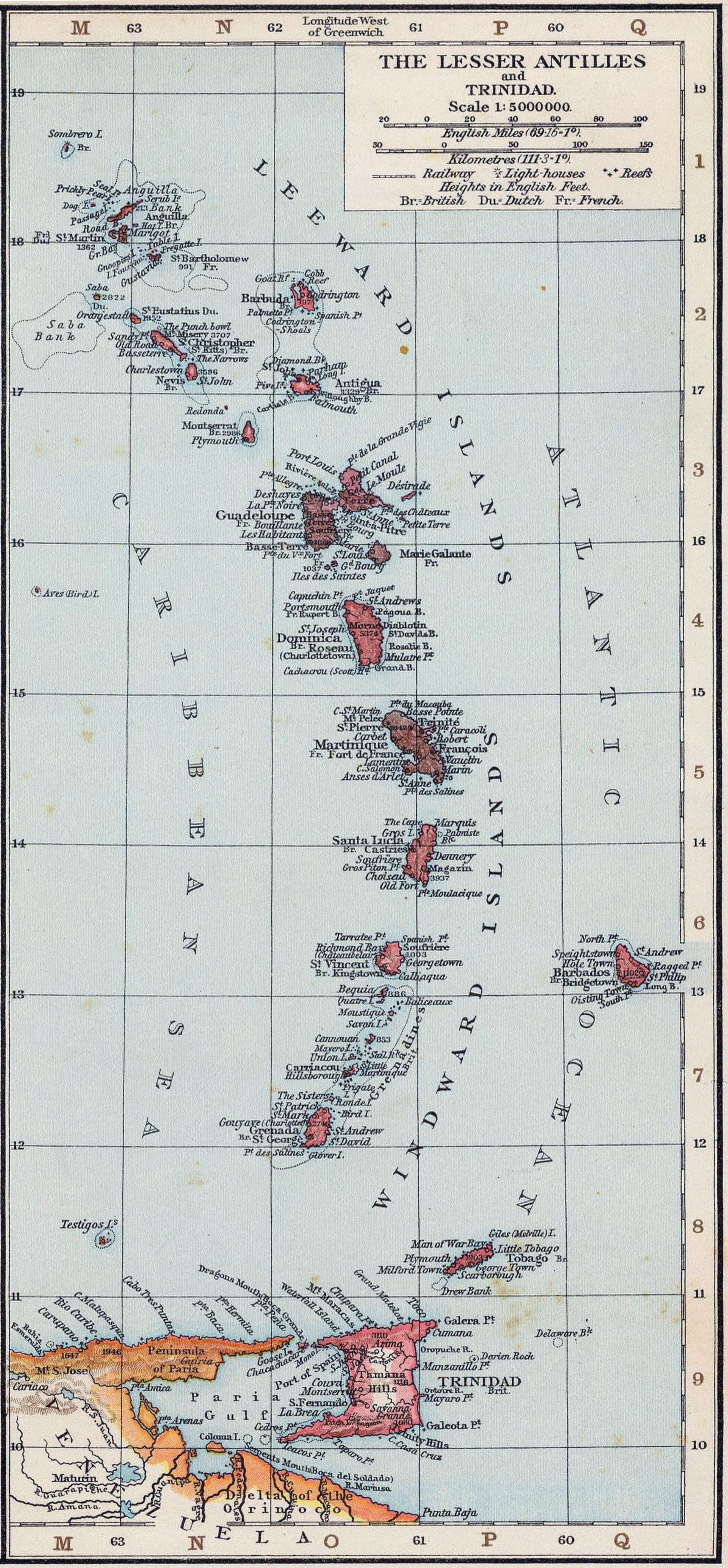

In the words of David Armitage and Michael J. Braddick, the European Atlantic World was one of ‘kaleidoscopic movements of people, goods and ideas’. During the 18th and 19th centuries the Caribbean was one of shifting loyalties, ownership and slavery. Islands would pass between the leading European powers over the course of the 1700s as a result of various peace settlements and wartime acquisition – Trinidad was one such island, passing between the British and Spanish multiple times over the course of the century.

John Black, born in 1753 appears to have been, in a broad context, a relative nobody – but when encountering Trinidadian history, he certainly became a somebody. He had rose to become a prominent member of the islands plantocracy, ‘he had in his way, much to do with the creation of Trinidad and its fundamental shaping’. In more recent works dealing with the Irish history of the Caribbean or specifically that of Trinidad – Black plays what Jonathan Wright characterises as a supporting role in the Picton Affair, and it is this episode I want to focus on today in order to discuss the life of Black.

We can learn a lot from the letters which survive from Black and his time in Trinidad, they differ quite a bit from the letters of Michael Keane in that they deal little with business and are often casual and informal correspondence to his family back in Belfast. Thus, what we get is a lot of information about West Indian life – the political instability, slavery (though indirectly) and plantation management, family life in the Atlantic world, debt, commercial interests, transatlantic patronage networks and the mercantile and political ties which linked Belfast and the West Indies.

Most importantly, like Keane, the letters of John Black bring us face to face with an Irish slave owner and trader. It is key to understand that the trafficking of humans from the continent of Africa across the Atlantic had a profound impact on both the Irish who emigrated across to the colonies in the Indies and America and it had an even greater impact on the economy back home – Nini Rodgers is a must read on this topic. Blacks letters themselves, when dealing with slavery, it must be said, are incredibly evasive, he made references to enslaved people but never mentioned the sheer level of violence which underpinned their lives.

Black was a member of a very well-established Ulster merchant family (his father George Black was Mayor of Belfast) which had made a name for itself in the previous century. This was a result of being connected to a flourishing town such as Belfast during increased trade and industrialisation – Black’s grandfather characterised Belfast as a place of ‘smoke, hurry, bustle and noise’. This wider Atlantic world, was on of fractured families, where some spent their lives away from family making a name for themselves, or not – for better or worse, in colonial ventures far from home, Black is one such example.

Black left Ireland for the West Indies in 1771 and never returned. Settling first in Grenada for over a decade, then moved on to Trinidad in 1784. There are a number of reasons why Black may have made this move at this point in his life but it is largely due to the building up of significant debt due to failed business ventures, combined with a tarnished reputation after defrauding a Liverpool based slave trading partnership called Baker & Dawson. A contract had been agreed between the partnership and the Spanish Crown for the sale of slaves in south America, with Black and a friend, Edward Barry to assist. Once the two received the shipment of slaves they kept any money presented, Barry took half to North America, while Black took the remainder to Trinidad.

Trinidad was at this point in time a neglected Spanish colony off the coast of South America, it like St Vincent was a frontier society dependent on slave labour but even still, various incentives were put in place to boost immigration. Spanish authorities welcomed any and all catholic settlers to the island which meant ‘natives of Ireland were received without examination…the catholic faith being in the Spanish idea, as inherent to that nation as our own’. Similarly, and more importantly for Black, new settlers to the colony would see all previous debts ignored and forgotten about and were also to be gifted grants of land, the size of which depended upon the number of slaves were accompanying them in the move. Thus, with all this in mind, it made the perfect fit for Black to start anew, and explains his decision to assist in defrauding Baker & Dawson in 1784, and to bring his share of the slaves to that island.

Black, to a degree, thrived in Trinidad and had certainly seen more success than his earlier West Indian ventures. While the average plantation in the 1790s saw a slave population of around 50-60 – Blacks plantation, Barataria, had up to 180 slaves working within it. By the beginning of the 19th century, he had made such a name for himself within the colony’s plantocracy that the new British Governor Thomas Picton remarked that he was ‘one of the most respectable and opulent proprietors of the colony’. It is here that we can see the transition of Blacks character, from an Ulster nobody, to a Trinidadian somebody – and while Picton seemed distantly fond of Black, this relationship in coming years would grow in the face of serious allegations against Picton.

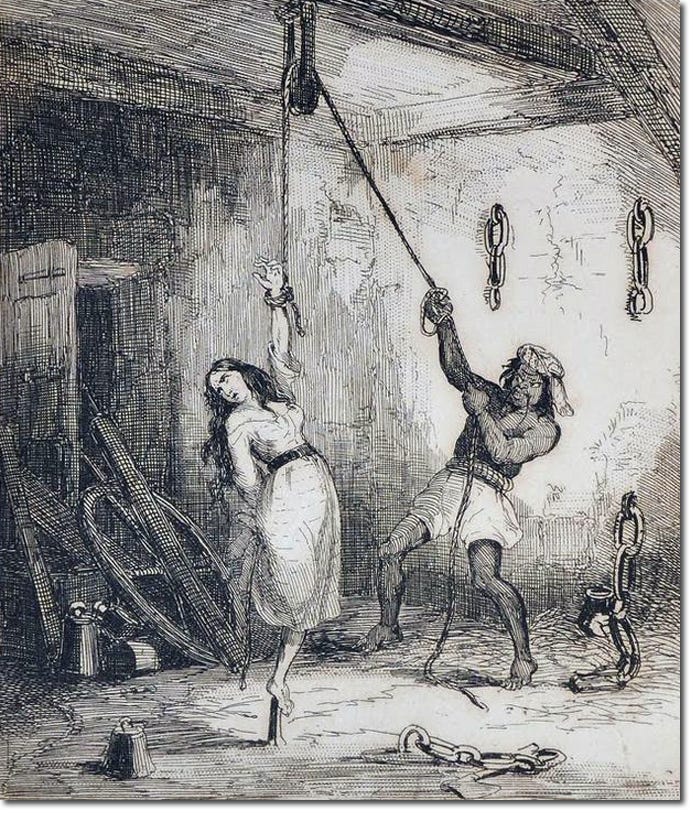

From 1802-1808 the role of Thomas Picton as the islands governor came under intense scrutiny as allegations of arbitrary rule, and extra-judicial torture and executions were levelled against him. Picton had been in charge as Governor of Trinidad following the capture of the Island by the British in 1797, and in the Peace of Amiens, it was decided that it would remain in British hands. By 1802 however, accusations had already made their way home regarding Picton’s brutality, whose policy was one led by fear. In 1802, William Fullarton (1754–1808) was appointed as the Senior Member of a commission to govern the island, Samuel Hood became the second member, and Picton himself the junior.

Both Picton and Fullarton came from drastically different backgrounds and their approach to governing the colony took on two very different visions – Fullarton preferred a more humane approach to suppression unrest and dissatisfaction – and the relationship between the two deteriorated rapidly. Fullarton commenced a series of open enquiries on allegations against Picton and reported his unfavourable views on Picton's past actions at length to meetings of the commission. In December 1803 he was arrested by order of the Privy Council on charges brought forth by Fullarton. The Privy Council mainly looked to accusations of excessive cruelty in the detection and punishment of practitioners of Obeah, severity to slaves, and the execution of suspects without due process. The charges were difficult to bring to fruition though, Pictons defence was that he was at the time following Spanish law as it was still the law of the land prior to the Peace of Amiens. In Spanish law torture was permitted and under martial law in a time of war, extra judicial executions were permissible - and he was under explicit direction from Hood to follow Spanish Law while governor of the island.

But, where does John Black fit in to all of this? Well, Black mad a name for himself for his role in assisting Picton in the political battle which took place between Picton and Fullarton in 1802-3. Fullarton himself highlighted the role of Black in the entire affair: ‘Mr Black in the hand of Brigadier General Picton became one of the chief instruments of injustice, terror and oppression’. Similarly, there are a number of contemporary sources which talk of Blacks role as a judge on the island, during and after Picton’s tenure, in which he sanctioned the use of torture simply because he could under the existing legal conditions.

These examples indicate just how violent the West Indian world could be, in 1801 a commission which included Black was established. The island planters were convinced that the high mortality rate amongst their slaves, was a self-inflicted conspiracy and the commission was tasked with figuring out what that conspiracy entailed. The island was reduced to gruesome spectacles of torture, mutilation and in at least one instance, a slave was dressed in a sulphur-filled shirt, and burned alive. This, is the world that Black not only inhabited, but actively participated in and not as a peripheral figure. He had come to wholeheartedly endorse the world view of the classic planter in the West Indies, genuinely believing that Africans were better off enslaved instead of free, and came to view free blacks in the colony with suspicion. It thus makes sense then, that when we see Black earnestly defending the actions of Picton while governor of the island, he was in a way also defending himself and his own actions.

He still maintained the self awareness to recognise the dramatic difference in social norms between the West Indies and Belfast. His letters home reference slavery, but remove any notion of brutality or violence which it entailed. In a letter from January 1803, he explains that he derives a certain satisfaction from seeing his slaves work a field, instead of seeing a single white farmer toil over acres of land, ‘To see 100 negroes holing a piece of cane land to a chosen song led by one of the numbers is wonderful odds to an active mind’. This is but one image he conjures up of slavery for his family back home in Belfast, but it is, like every other reference in his letters, and incredibly sanitised one, which shields his wider family from the reality and brutality of slavery in the West Indies.

Much like Michael Keane, in my last blog, Black tries to gloat about the welfare of his slaves in comparison to others. He highlights that he built a hospital, while ignoring the fact that he was forced to by Governor Picton and it ultimately would have represented a commercial decision rather than a moral one. Which really sums up Blacks attitude entirely to the enslaved. Wright highlights that what underpins every decision and opinion Black held about enslaved people, was commercial calculation, which was true of most, if not all slave owners and traders.

John Black, a member of a large and well-established Ulster mercantile family was a man who represents many from Ireland in this time who went abroad, into the imperial networks to try and make it, to distinguish themselves in any way they could. In doing so he appears at times as an unpleasant and self-pitying character, and from outsider accounts, he comes across as a cruel and evil character, with whom power never should have been trusted. His letters give us an insight into island politics, opinions on slavery and on a personal level, reveal the life of a failing merchant and plantation owner, debt ridden and in a self-imposed exile of sorts. We can learn a lot from his letters and from the events which he formed but a fragment of, his life can help us to better understand the world he inhabited in the Atlantic world, which encompassed the Caribbean and Ulster equally, a world characterised by revolution, war and political instability.

Much more can be said about him and the world he inhabited, his letters also show us the disconnect which existed in his own mind about notions of civility, and his choice to send his mixed race children back to Belfast to be raised and education. We can also see similar fears to those expressed by the O’Rourke family in a past post I wrote – Black speaks in detail about his paranoia towards freed slaves, whether legally or runaways, and of the risk that revolts in neighbouring islands may spread to Trinidad. It shows us that the fear of those they ruled over, was someone which never escaped the minds of planters and perhaps explains the knee jerk reaction to such extreme violence when their fears were, in their own minds, proven.

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

Jonathan Jeffrey Wright (ed.), An Ulster Slave-Owner in the Revolutionary Atlantic: the Life and Letters if John Black (2019).

James Epstein, Scandal of Colonial Rule: Power and Subversion in the British Atlantic during the Age of Revolution (2012).

Nini Rodgers, Ireland, Slavery and Anti-Slavery: 1612-1865 (2007).