Attorney General Michael Keane of St Vincent, 1787-90.

A glimpse into the wider Irish Atlantic world of the late eighteenth century

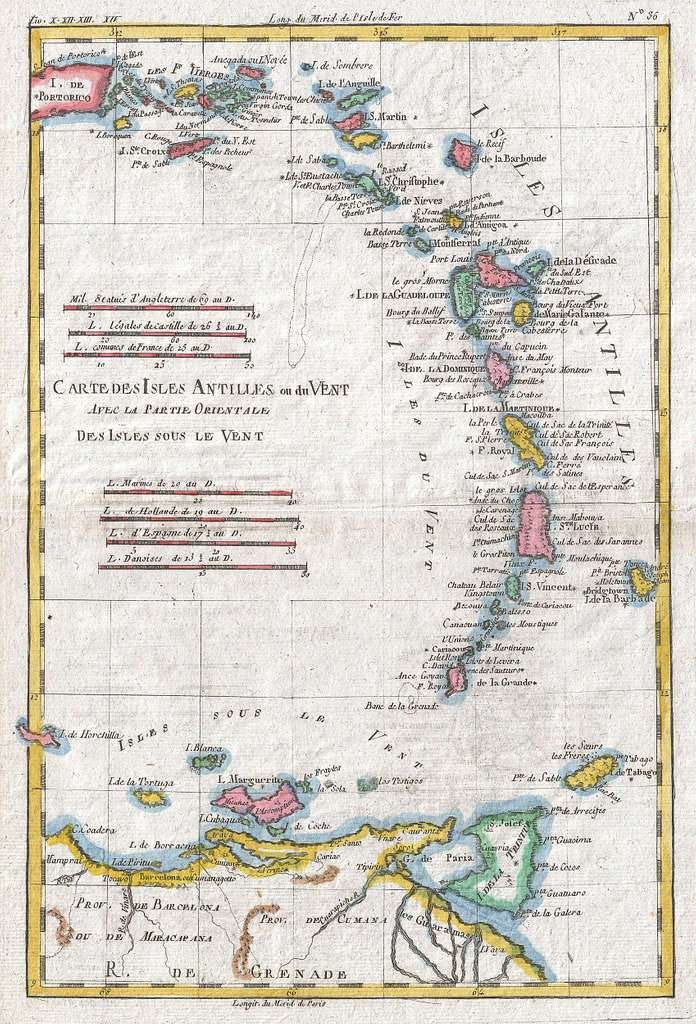

I spoke in a previous post about the O’Rourke sisters and that the history of Irish involvement in the Caribbean world, and specifically with slavery is an under-explored one. There are indeed some fantastic books out there which represent great efforts to better understand Irish involvement in this world and for the next couple of blogs I want to examine some of them. The first is the life of Michael Keane, a colonial official and Attorney General of St Vincent. The second will be the life of John Black, a Belfast born planter and influential political figure in Trinidad.

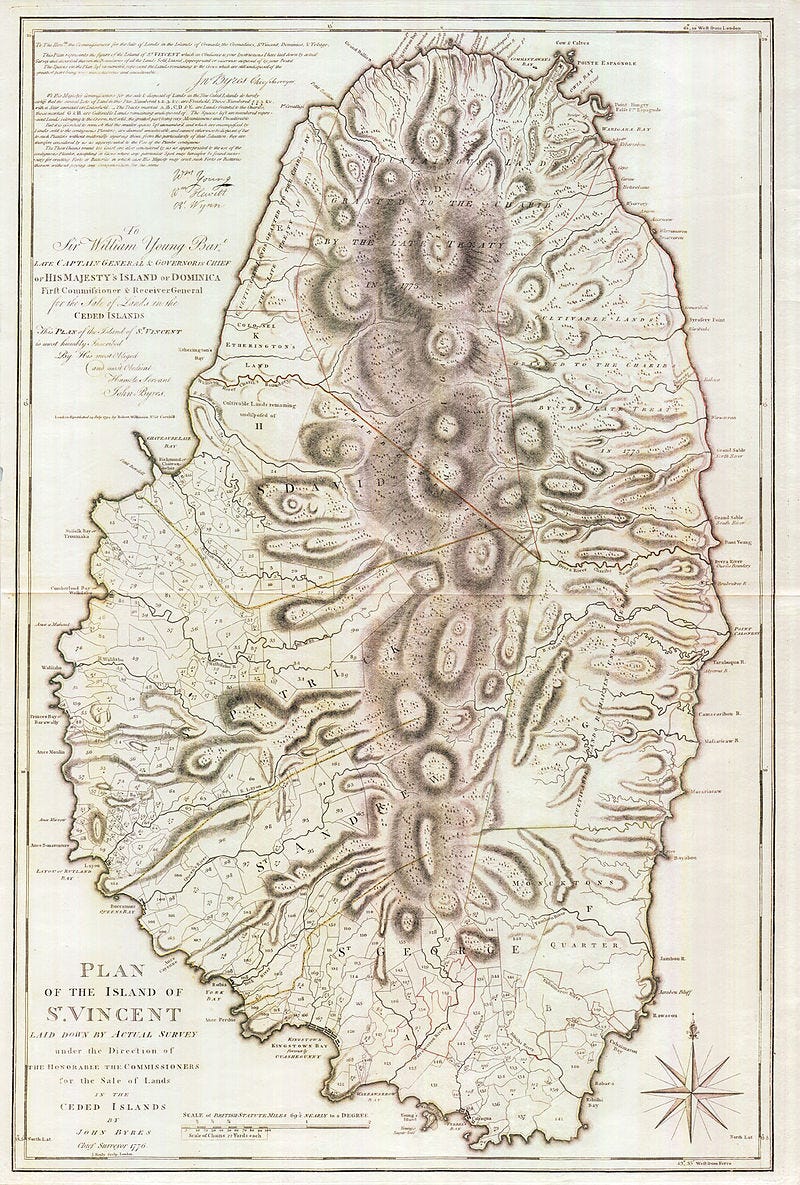

For Michael Keane, Mark S. Quintanilla has edited and made accessible the letter book of the Attorney Generals time in St Vincent from 1787-90 and it paints a picture of interconnected trade networks spanning the Atlantic world from Ireland and Britain to the Caribbean/West Indies and North America. This letter book evidences growing Irish interest in the region and Keane represents but one Irish figure which can be found active in the area at this time. His letter book is also but a small insight into his life, Keane spent most of his life in the Caribbean, residing first in Barbados, and from 1763 onward in the Ceded Islands, permanently residing at St Vincent.

Born in Ballylongford, County Kerry, Keane relied on many of the relationships established between Irish mercantile families in the Atlantic world to make his way. He assisted and represented many in the Irish Atlantic – including Catholic, Protestant and non-conformist merchants alike. His primary function as a colonial attorney general was working with absentee Irish West Indian planters from across the Caribbean – Barbados, Nevis and St Kitts mainly. He stood at the centre of a complex web of associates located throughout the British Atlantic Empire and though a citizen of this massive world, he remained steadfast in his identification as ‘wholly Irish’.

While at a glance, Keane appears to be of Anglo-Irish stock, a matter which some deem to be enough to make him no longer Irish – Keane’s claim of being ‘wholly Irish’ eschews any strong connection to the Anglo-Irish elite, or the Church of Ireland, suggesting that his conversion to the Anglican faith was a matter of political pragmatism rather than a confession of faith as it would have been a necessary step to take in order to engage in work as a colonial official.

During his 25 years at St Vincent, Keane established a promising fortune relying upon Irish association. He frequently acted on behalf of Irish interests by evoking common experiences, while asserting his British identity when interacting with English and Scottish contacts. This illustrates brilliantly the way in which many of the Irish in imperial networks navigated a world in which multiple identities were required in order to ‘make it’ in the broader imperial framework. For many the empire provided an opportunity, a gateway to enterprise and fortune.

Keane proved to be politically savvy in his ability to network with those in important positions – he was first a colonial agent in London and became close with Lord Shelbourne, future Prime Minister. When he first arrived on the island of St Vincent, he had no chance of joining the elite planter class already formed, but came to be one among a small group who emerged to dominate island affairs as a colonial administrator.

Thanks were due to his ability to successfully court Shelbourne, during his time as colonial agent in London.

In a letter dated 15 December 1781, Keane said;

‘It has not been for want of a due sense of the attention and civilities I received at your hands whilst I was in London…that I have not frequently since expressed my acknowledgements to you.’

Shelbourne’s patronage was not something Keane took for granted, nor was his courting limited to Shelbourne alone. There is proof that he sought the patronage of many leading Whig figures in the government and while the extent of correspondence is limited now, there is proof that he sought to curry favours by continuously supplying them with exotic produce from the Caribbean;

Once in the Caribbean he would continue to court, or attempt to court his patrons with a continuous supply of exotic produce – ‘these exotic delicacies tied his remote colony to Whitehall and curried favour with aristocratic families’.

‘Wrote to Lord Sydney and sent him a box with a pot of preserved ginger, one of tamarinds, and another of pickles with 12 rolls of chocolate per Ca. Hooper. Wrote also to the Marquis of Lansdowne and sent him a large jar of Tamarinds and 12 rolls of chocolate per same.’

‘If your lordship will permit me, I will in the beginning of the next crop procure 100 lbs of the best species of cocoa [for your use].’

Keane in time came to establish himself as a planter with two plantations to his name – Liberty Lodge and Bow-wood. These rarely make entries into his letter book but from a 1797 estate inventory we know that Liberty Lodge was 115 acres in size, 41 of which was used for the cultivation of sugar. Bow-wood was 130 acres in size with only 30 being used for sugar – the remainder on each estate was used for pasture. In total Keane is recorded as holding 121 slaves across both properties and in his own experience of owning slaves we see the ‘benevolent’ attitude of some slave owners, claiming that theirs were the best treated than any around; ‘No negroes in St Vincent have lighter work or are better fed than mine’.

As a frontier society, St Vincent was like many others, perpetually short on labour meaning the dependence upon enslaved humans was immense – to the point that some individuals sought to capitalise further on the trade. Keane notes in his letters that some who owned small numbers of slaves sought to rent them out to plantations for the purpose of short-term labour. Much of his correspondence which deals with the practice of slavery is in relation to his client’s property – it is uncomfortable reading as they are rarely referred to as individuals, as people, but merely as commodities and the defects and poor treatment which would likely impact their value. It serves to highlight just how commonplace and normal the practice was. As his letter book is solely for his business practice, we have little indication of what differing opinions existed if any among the merchants he worked for.

His correspondence interestingly also gives evidence to a broad Irish participation in Atlantic trade;

‘By building familial and kinship networks the Irish were able to diversify their assets by expanding colonial trade, cultivating ties with Anglo-Irish aristocrats, and promoting trusted members of the Irish gentry, who in turn could gain access to British social networks’

The Irish gentry emerged as cross-cultural brokers who had legitimacy among local families, regional commercial centres and broader imperial interests. Keane’s role in this world makes clear that he himself became an Irishman who wielded considerable influence in the Irish Atlantic world. His activities as a colonial bureaucrat and West Indian planter broadened the trans-Atlantic web that radiated from Ireland.

He proved so influential that there is even evidence that during his time as Attorney General, not only did he represent those on the island of St Vincent but he was also sought out by Irish families from across the West Indies for their Irish connection alone, this includes extending beyond the bounds of the British Empire. His correspondents often pursued trade in neighbouring islands belonging to the Dutch, French and Spanish colonial empires and their trade networks likely included much of Spanish Central and South America.

The story of Michael Keane is but a tiny glimpse into the world of the Caribbean that some Irish men and women inhabited. The world that the O’Rourke sisters inhabited ultimately set them up for disaster, due to their gender and expected roles in society. The same cannot be said of Michael Keane, a man whose career flourished in the colonial administration, because of his effectiveness as an agent, but also because of his dual identity has Irish and British.

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

Mark S. Quintanilla, An Irishman’s Life on the Caribbean Island of St Vincent, 1787-90: The Letter Book of Attorney General Michael Keane (2019).

Nini Rodgers, Ireland, Slavery and Anti-Slavery: 1612-1865 (2007).

Trevor Burnard, Planters, Merchants, and Slaves : Plantation Societies in British America, 1650-1820 (2015).