The day is 14 July, the thirty-second year of George III’s reign (1792) and crowds are amassing throughout Belfast town in anticipation of a great celebration for the second year running. Last year was impressive but this years is to be one for the ages – organised by the Volunteers with assistance from the United Irishmen.

All along the main thoroughfare can be seen women and children wearing green ribbons in their hats and hair – anywhere that green can be worn or displayed, it can be seen. The population of the town had swelled by the thousands, many travelling from the surrounding areas and some from as far as Dublin to attend.

At last, at 9AM the rolling of drums could be hear coming from afar – distant cheers begin to erupt slowly moving closer like a ripple affect upon the crowd. Volunteers Regiments paraded their way down the street, drums beating, colours flying as if ready for war.

Flags from across the Atlantic and European world could be seen. All flown in celebration or support of their efforts at liberation and reform. Each flag flew with an accompanying motto - drawn from the works of Paine and Rousseau. Ireland: Unite and Be Free, America: Asylum of Liberty, France: The Nation, The Law, and The King, Poland: We will Support it, and Great Britain: Wisdom, Spirit and Liberality to the People.

Among them, Theobald Wolfe Tone rode on horseback in full regimentals – he went with the Volunteers to the Falls for review where thousands of spectators were gathered, here he spent most of the time in a ‘council of war’.

When we left last time in Part One, we had just finished with the Irish Volunteers of the eighteenth century – their inception, meteoric rise and abrupt fall from grace on the Irish political landscape. As I said before, the Volunteer Conventions of 1783 were not to be the last of the Volunteers in public life. They continued to exist in the background, they remained a place for the expression of political thought – primarily operating as political clubs where people could parade, drink and eat and debate enlightenment thought.

Their numbers dwindled but nonetheless their existence persisted, posing little threat to the political order after 1782’s sweeping concessions on the Irish Parliament. It is at the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 that we see a certain resurgence in Volunteering. It is important to not overstate this however, despite a re-invigoration of Volunteering, numbers remained minimal and largely inflated by supporters. Some calculated numbers in the thousands, like Wolfe Tone when lobbying for French war support - others, like William Drennan were more accurate, claiming to have but hundreds across the island. A far cry from the c. 40,000 involved in the first wave of Volunteer/Patriot politics.

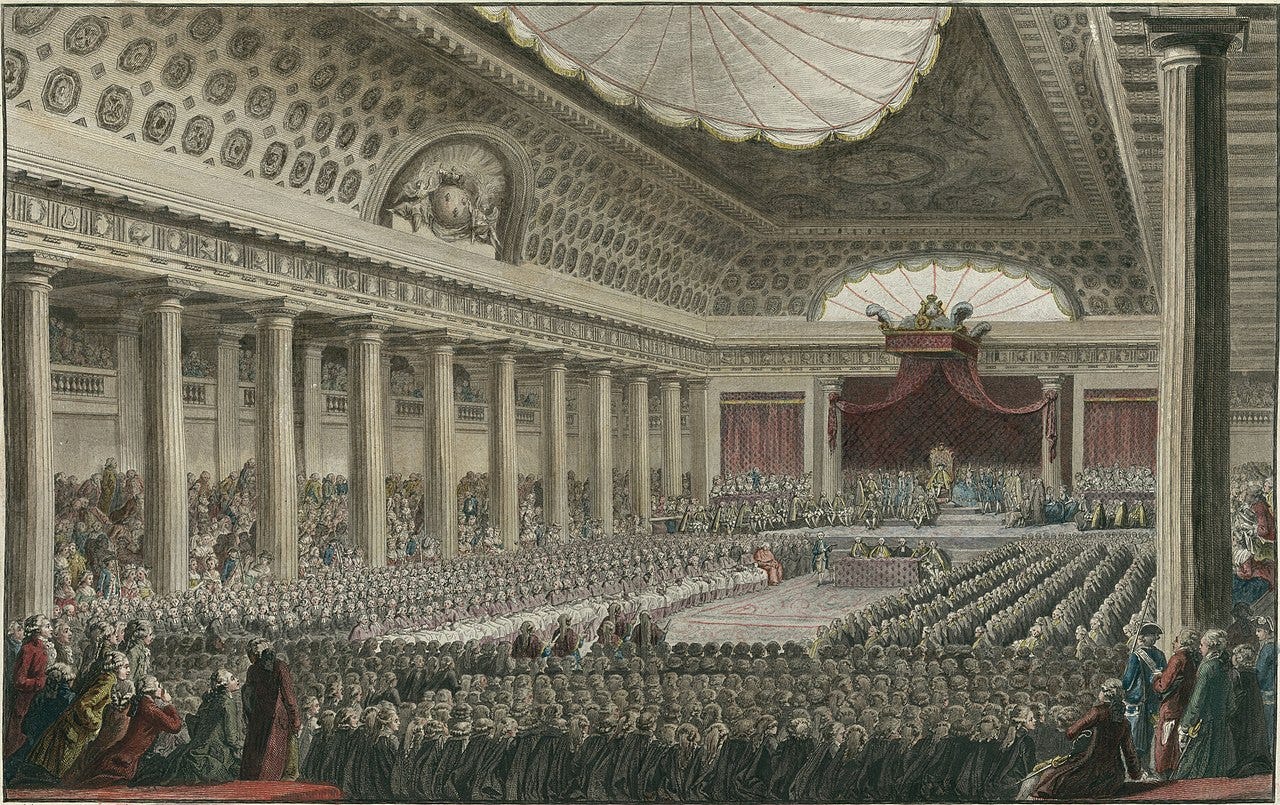

The Volunteers welcomed the French Revolution as did many reform movements around the British Isles. They saw the outcome of the Estates General as the expression of a nations people to push for legislative reform – if Europe’s most absolutist monarchy could be brought to its knees by political reform, then it was possible anywhere. For many involved with Volunteering, it was viewed as a new dawn for the enlightenment in Ireland - and it as met with celebrations.

We know Volunteer celebrations took place on 14 July 1791 and 1792 in Belfast where they paraded, ate, drank, and saluted to the Fall of the Bastille and the French Revolution. In 1792 however there is a new presence, The Society of United Irishmen – a political reform society, sharing in the revolutionary optimism and placing themselves on a pedestal. The 1792 parade saw great involvement from United Irishmen, and accounts of planning and the course of the day remain accessible to us from the likes of Theobald Wolfe Tone, William Drennan and Henry Joy McCracken.

On 14 July 1792, at 9AM the different corps paraded down High Street. A total of 790 Volunteers paraded through the town to the review ground in the Falls where a reported 20,000 spectators had gathered. At 3PM the parade marched back into Belfast town and were joined by hundreds of people sporting green ribbons and laurel leaves in their hats.

Once back in the town – they gathered at the White Linen Hall where both William Drennan and Wolfe Tone were asked to give addresses. Drennan had the easy task of addressing the National Assembly in Paris – issuing a proclamation of support. Tone stoked the fires of debate by addressing Ireland and calling for Catholic Emancipation. A debate broke out that raged for hours until 7PM that night. It was the first time an official position was debated over Catholic Emancipation.

Many, including those in the Volunteers thought the 1782 revisions to the Penal Laws enough - the Catholics should be free but not so free as to participate in politics in a meaningful way. Much like in 1783 when a number of ‘patriots’ broke ranks with the Volunteers because they achieved what they set out to do. It is here that internal cracks begin to develop.

The Belfast parade in 1792 highlights the peak of revolutionary optimism on a large scale in Ireland. From the end of the summer of 1792 as news of events in France reached Irish shores many who considered themselves moderates, and staunch believers of the political process began to look on with horror. It is really from the end of 1792 and into 1793 that people begin to lose faith in earnest.

In response to increasing tension abroad and the outbreak of war in 1793 political clubs in Britain and Ireland became targets of government censorship. What followed was the evaporation of the middle ground, of moderate political groups. Highlighted by Ultán Gillen below:

‘The period 1793-8 was one of intensifying governmental repression in response to the war and domestic political challenges. The expression of political opinion by the volunteers, public political clubs, even town meetings were closed off. The secret political club or society now became the main vehicle for the expression of political though and agitation for activists.’

Thus, from 1793 the Volunteers became largely extinguished in the face of this repression. The United Irishmen held a significant following and many within its ranks remained political reformers. But by 1794 a number of members had begun to harbour more extremist ideologies – to many the political process was failing them and they looked to France for further inspiration.

The crack down discussed by Gillen above resulted in the Volunteers being outlawed as a result of Gunpowder Act and Convention Act - which effectively ‘killed off volunteering’. Cracks had already been forming in the movement however. After Tones pronouncement of support for Catholic Emancipation and the vigorous debate it caused - many participants began to reconsider their involvement. As illustrated by Blackstock in his book listed below - after volunteering was outlawed, many joined the United Irishmen, but similarly many joined the Yeomanry in 1796.

In 1796 the Yeomanry were established to fulfil much the same purpose as the Volunteers with one key difference - they were established and controlled by the government, they were in a way the army of the ascendancy, of the status quo. Thus came the the culmination of years of polarisation. No longer were there groups who filled the middle ground of political opinion or thought. What existed, from the 1795-6 onwards was two polar opposites - the United Irishmen and Defenders, in favour of separation from Britain and the state itself.

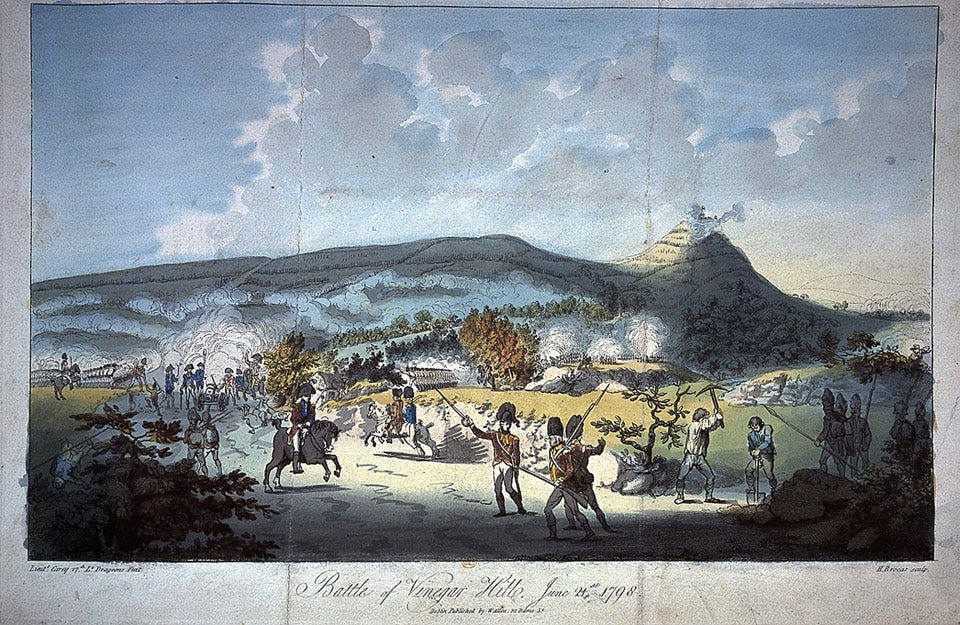

In the end, it would result in one of the most violent uprisings Ireland had and would ever see. More people would die in the 1798 Rebellion than the 1916 Rising, the War of Independence and the Irish Civil War combined. The polarisation of politics, the disintegration of Volunteering, and the radicalisation of the United Irishmen ensured that the gun was now centre stage for Irish politics. After 1798 Ireland would be brought into the Union of England, Scotland and Wales - ensuring the removal of said gun, as the state would hold a monopoly on violence until the twentieth century.

Ireland in the 1790s to me, symbolises very generally what we risk happening when the middle ground dissolves entirely. When we enter into a world of incredibly polarised politics - where policy is dependent on one extreme or the other, we enter dangerous waters. The bloodshed of 1798 was the result of - in my humble opinion, poor planning on the part of the state. The reactionary way in which reform was stifled and the ability to debate outlawed, forced groups underground and into hiding. This further radicalised a group determined to see change.

As seen in the dissolution and redistribution of Volunteers, many of those involved filled that middle ground and found themselves left with joining a radical separatist movement or the Yeomanry. One must wonder, if Volunteering remained in place and if members were left to vote with their feet in the late 1790s - which way would they have walked? How much did government suppression simply speed up the clock of rebellion?

Sources:

Ultán Gillen, ‘Opposition political clubs and societies, 1790-8’ in J. Kelly and M. J. Powell (ed.), Clubs and Societies Clubs and Societies in Eighteenth-Century Ireland (Dublin 2010).

Allan Blackstock, Double Traitors: The Belfast Volunteers and Yeomen 1778-1828 (Belfast, 2000).

Marianne Elliott, Tone: A Biography (Liverpool, 2012).

You will find the Belfast publication the Northern Star remained fully informed of all the tumultuous events in France and supported the revolution.