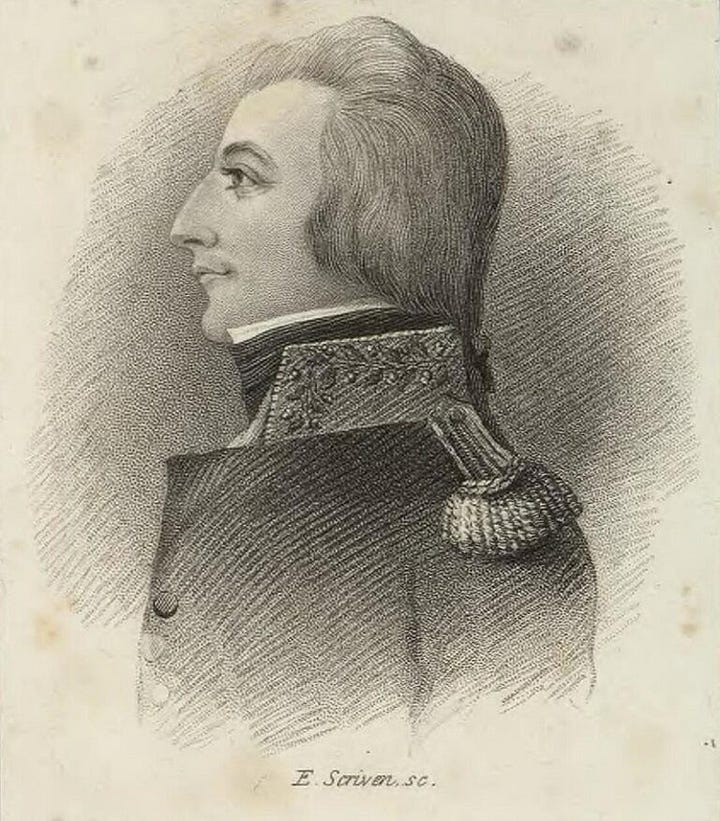

View of Ireland by T. Wolfe Tone, April 1794.

A memorandum written by Theobald Wolfe Tone at the request of Rev William F. Jackson, April 1794.

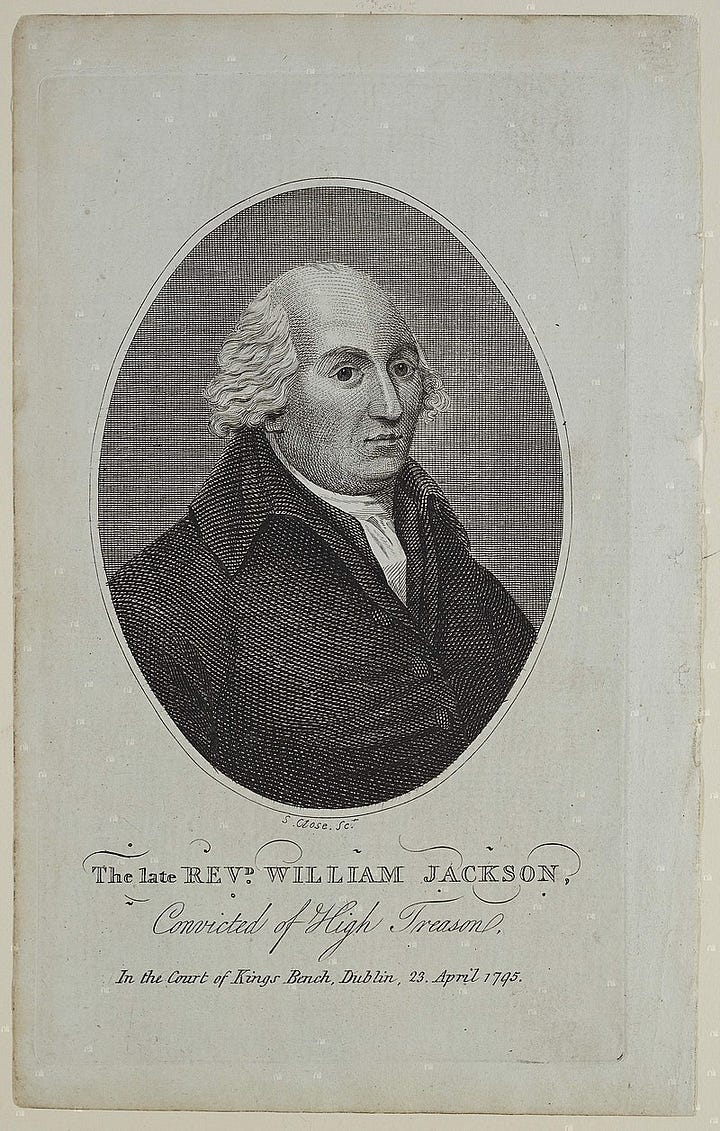

The below is a memorandum written by Wolfe Tone in April 1794, the purpose of which was to indicate Irish willingness to welcome a French invasion so as to throw off the yoke of British imperialism. It is this memo, which Rev. William F. Jackson had sent to France in the open post, that was intercepted by the Postmaster General of Dublin, and which led to the arrest of Jackson. This arrest further implicated Wolfe Tone, Archibald Hamilton Rowan, and Leonard McNally thus drastically altering the political direction of the United Irishmen, and setting them on a path to radicalism.

The situation of Ireland and England is fundamentally different in this: the government of England is national-that of Ireland, provincial. The interest of the first is the same with that of the people; of the last, directly opposite. The people of Ireland are divided into three sects-the Established Church, the Dissenters, and the Catholics. The first-infinitely the smallest portion-have engrossed, besides the whole church patronage, all the profits and honours of the country exclusively, and a very great share of the landed property. They are, of course, aristocrats, adverse to any change, and decided enemies of the French Revolution.

The Dissenters-who are much more numerous-are the most enlightened body of the nation; they are steady Republicans, devoted to liberty, and, through all the stages of the French Revolution, have been enthusiastically attached to it. The Catholics-the great body of the people-are in the lowest degree of ignorance, and are ready for any change, because no change can make them worse. The whole peasantry of Ireland, the most oppressed and wretched in Europe, may be said to be Catholic. They have within these two years received a certain degree of information, and manifested a proportionate degree of discontent, by various insurrections, &c.

They are a bold, hardy race, and make excellent soldiers. There is nowhere a higher spirit of aristocracy than in all the privileged orders, the clergy and gentry of Ireland, down to the very lowest; to countervail which, there appears now a spirit rising in the people which never existed before, but which is spreading most rapidly, as appears by the Defenders, as they are called, and other insurgents. If the people of Ireland be 4,500,000, as it seems probable they are, the Established Church may be reckoned at 450,000; the Dissenters at 900,000; the Catholics at 3,150,000. The prejudices in England are adverse to the French nation under whatever form of government. It seems idle to suppose the present rancour against the French is owing merely to their being Republicans; it has been cherished by the manners of four centuries, and aggravated by continual wars.

It is morally certain that any invasion of England would unite all ranks in opposition to the invaders. In Ireland-a conquered, oppressed, and insulted country-the name of England and her power is universally odious, save with those who have an interest in maintaining it; a body, however, only formidable from situation and property, but which the first convulsion would level in the dust. On the contrary, the great bulk of the people of Ireland would be ready to throw off the yoke in this country, if they saw any force sufficiently strong to resort to for defence until arrangements could be made: the Dissenters are enemies to the English power from reason and from reflection; the Catholics, from a hatred of the English name.

In a word, the prejudices of one country are directly adverse to the other-directly favourable to an invasion. The government of Ireland is only to be looked upon as a government of force; the moment a superior force appears, it would tumble at once, as being founded neither in the interests nor in the affections of the people. It may be said, the people of Ireland show no political exertion. In the first place, public spirit is completely depressed by the recent persecutions of several. The convention act, the gunpowder, &c., &c., declarations of government, parliamentary unanimity, or declarations of grand juries-all proceeding from aristocrats, whose interest is adverse to that of the people, and who think such conduct necessary for their security-are no obstacles; the weight of such men falls in the general welfare, and their own tenantry and dependents would desert and turn against them.

The people have no way of expressing their discontent civiliter, which is, at the same time, greatly aggravated by those measures; and they are, on the other hand, in that semi-barbarous state, which is, of all others, the best adapted for making war. The spirit of Ireland cannot, therefore, be calculated from newspaper publications, county meetings &c., at which the gentry only meet and speak for themselves. They are so situated that they have but one way left to make their sentiments known, and that is by war.

The church establishment and tithes are very severe grievances, and have been the cause of numberless local insurrections. In a word, from reason, reflection, interest, prejudice, the spirit of change, the misery of the great bulk of the nation, and, above all, the hatred of the English name, resulting from the tyranny of near seven centuries, there seems little doubt but an invasion and sufficient force would be supported by the people. There is scarce any army in the country, and the militia, the bulk of whom are Catholics, would, to a moral certainty, refuse to act, if they saw such a force as they could look to for support.

Further Reading:

Moody, McDowell, Woods, The Writings of Theobald Wolfe Tone 1763-98: Volume I: Tone's Career in Ireland to June 1795 (2009).

Great letter. Thanks.