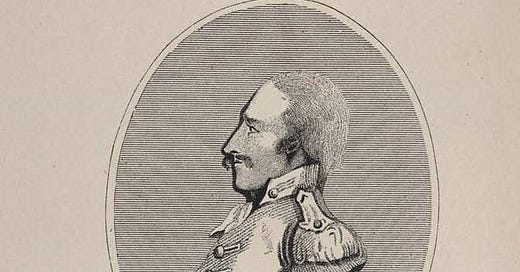

Some historical figures live such extraordinary lives that their stories seem almost implausible. George Thomas is one such figure—a man from a poor Catholic farming family in Tipperary who rose to rule a kingdom in northern India. His journey was marked by ambition, resilience, and military prowess, making him a fascinating case study of the intertwined histories of Ireland and India.

Thomas emigrated to Britain around 1776 and, in 1780, either joined or was forced into the British Navy by a press-gang in Bristol. Impressment—the practice of forcibly enlisting men into military service—was common at the time, particularly in times of war. While it mainly targeted merchant sailors, apprentices and laborers were often taken as well.

By late 1781, he was halfway across the world as a sailor, at Madras on the subcontinent of India, where he promptly deserted from the Navy: ‘overcoming the lowliness of his situation, he determined to quit the ship, and embrace a life more suitable to his ardent disposition’. He made for the mainland where he became a mercenary for hire, having fallen in with a group of Poligar brigands.

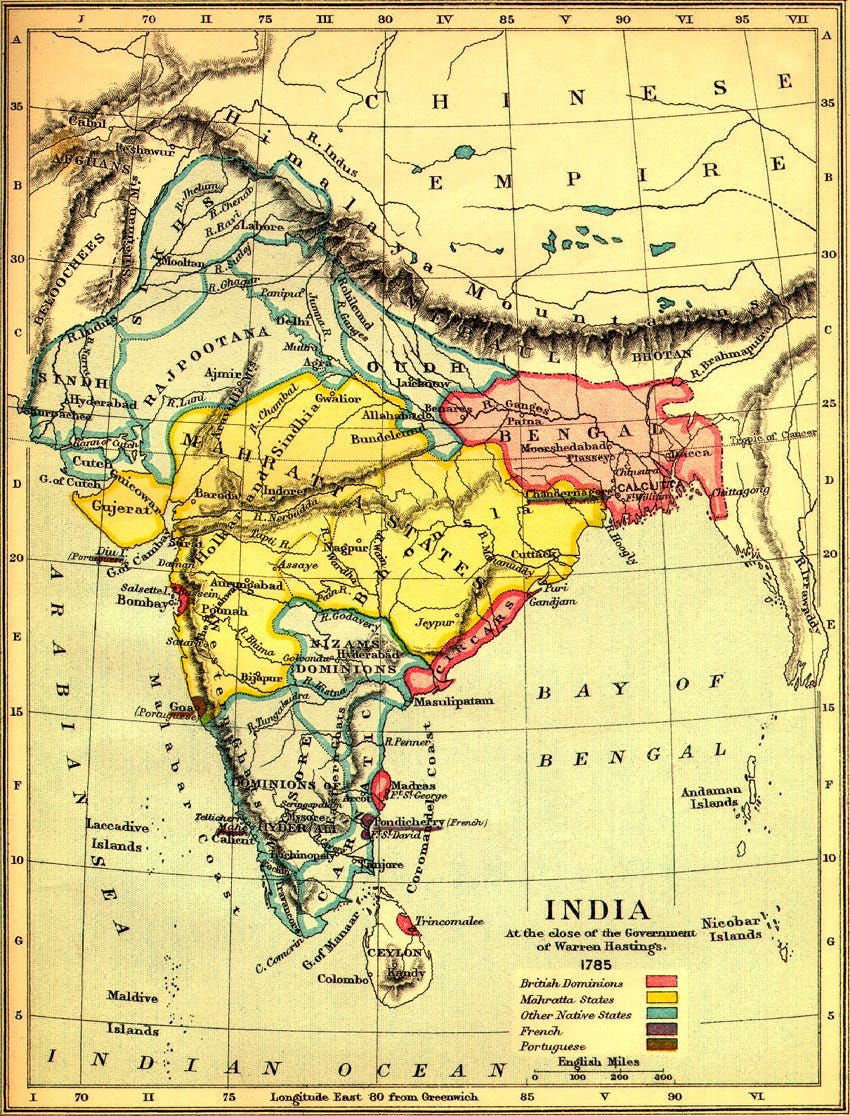

He raided and pillaged his way northwards for a number of years until reaching Delhi in northern India in 1787 where he was commissioned to the service of the Begum Sumroo, Princess of Sardhana. His military prowess and strategic genius quickly made him a favourite general and later they became lovers.

“Soon after his arrival at Delhi, the Begum, with her usual judgment and discrimination of character, advanced him to a command in her army”.

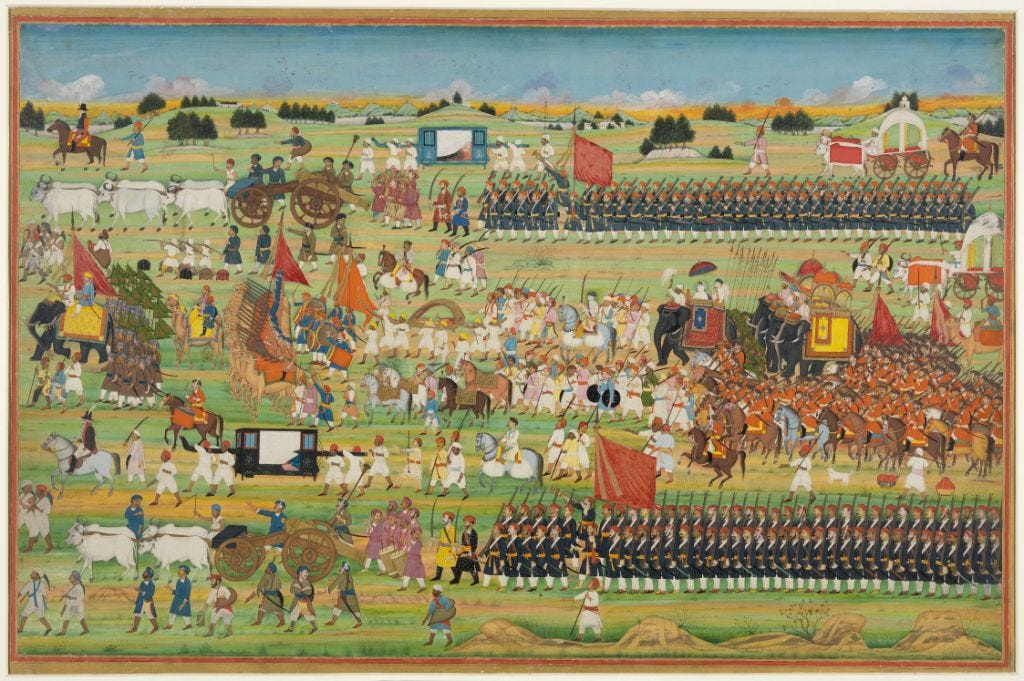

In 1788 the Begum joined forces with the Mughal Emperor, Shah Alam, in the campaign against the rebellious nobleman Najaf-Quli Khan, where Thomas played a key part in the siege of Gokulgarh. In his various military ventures against the Sikh’s to the northwest and many more of the Begum’s enemies, Thomas served himself well and worked to improve the presence, power and respectability of the Begum, so much so that he became her chief advisor and counsellor.

In spite of his devotion to the Begum, after six or seven years of loyal and effective service, he found not only his opinions as a counsellor, but his feelings as a lover to the Begum supplanted by another European member of her court, a French officer named Le Vassoult.

“This conduct in the Begum, exciting much animosity and many heart-burnings between the two rival commanders, Mr. Thomas resolved to embark his fortunes on a different service. He therefore quitted the Begum Sumroo, and about 1702 betook himself to the frontier station of the British army, at the port of Anopshire”

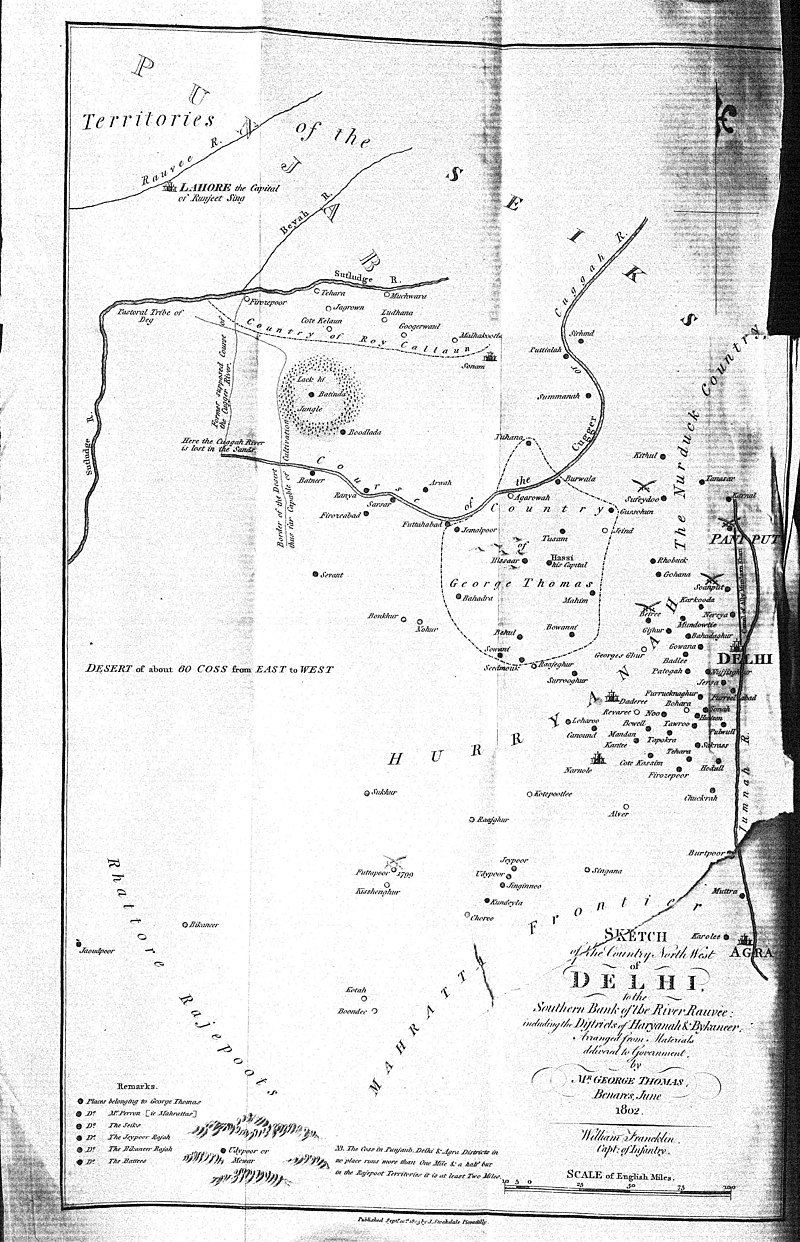

Thomas then aligned himself with Apa Khande Rao, a Maratha chieftain under Mahadaji Scindia of Gwalior. For four years, Thomas worked diligently, demonstrating his military prowess by subduing Rajputs of Rajasthan, Kachawa Shekhawat Thakur rulers of Haryana and Shekhawati, Mughals under vizir Mirza Najaf Khan and Bhatti Muslim Rajputs. He was later appointed governor of Jhajar with the responsibility of stopping Sikh incursions into Mahratta territory. He built the sizeable fort ‘Georgegarh’, north-west of Delhi, and a new military post at Hansi, soon establishing a power-base in the Nurduck country of Haryana, south of the Cugger River.

Rajah of Haryana, 1797-1802.

In 1797, following the death of his benefactor Apa Rao - Thomas took a leap of faith and decided to go it alone, declaring himself independent from the Marathas and entitling himself Rajah of Haryana - a man from Tipperary was now king of a modest domain in Northern India, just beyond the boundaries of Delhi. Showing just how much he learned about governance during his time under Begum Sumra and Apa Rao - he took steps to make his realm prosperous and to further legitimise his rule.

He minted his own coinage with his face on one side. By minting coins, he made a clear statement about his independence and his ability to carve out a place for himself as a strong ruler. These coins still survive as valuable artifacts of a tumultuous political and economic history of the region, and also serve to present us with an opportunity to glimpse the man and what he looked like.

In his biography which he dictated to Captain William Franklin following his fall from grace as the Rajah from Tipperary he said;

"I established my capital, rebuilt the walls long since decayed, and repaired the fortifications (of the 12th century fort of Prithiviraj Chauhan). As it had been long deserted, at first I found difficulty in providing for inhabitants. But by decrees, I selected between five and six thousand persons to whom I allowed every lawful indulgence. I established a mint and coined my own rupees, which I made current in my army and country; as from the commencement of my career at Jhajhar I had resolved to establish independence. I employed workmen and artificers of all kinds. I cast my own artillery, commenced making muskets, matchlocks and powder and in short, made the best preparations for carrying on an offensive and defensive war."

We must of course take anything from the individuals own words, with a grain of salt. Perhaps he did indeed make the best preparations for carrying out war - defensive or offensive. But ultimately his rule failed because he was in essence surrounded by enemies. He had, over a couple of years, managed to irritate enough of his neighbours by infringing on their lands, and conquering their territories that he had created a common enemy for them all, in himself.

By 1799 he had begun to encroach into Sikh, Rajput, and Mahratta territory; and the Sikh chieftains, aided by the European officers of the Mahratta ruler, Sindhia, mounted a campaign against Thomas. Despite such substantial alliances, Thomas managed to break free of a siege at Georgegarh and return to his capital at Hansi where he was again besieged by his enemies who had a combined force of 30,000 troops to his own army of 10-11,000 men. Ultimately he was forced to concede and surrender his city and kingdom.

Downfall and Demise

After just 5 years in power he was reduced once more to a landless and hapless Irishman, who happened to find himself in the Indian subcontinent. Despite all the trouble he had caused over the few years he was in power, he was able to negotiate reasonable terms of surrender. He was allowed to retain some of his wealth, so long as he agreed to return to Ireland - he was escorted to the border of British territory in the region and began a long trip to Calcutta, on the west coast of the Indian subcontinent.

It is during this journey to the coast that he began to dictate his life to William Franklin, a British officer escorting him to Calcutta. He dictated his memoirs in Farsi, the language he was most comfortable in, as he had become more well versed in this and other local dialects than he ever did in English or Irish, languages he was illiterate in.

George Thomas died at the age of 46, he was ‘tall in his person (being upwards of six feet in height)…he appeared formed by nature to execute the boldest designs; and though uncultivated by education, he possessed a native and inherent vigour of mind, which qualified him for the performance of great actions, and placed him on a level with distinguished officers of the present day’. Some high praise indeed, from Franklin who wrote Thomas’ memoirs and published them after his death in 1802.

Legacy

The Jahaj Kothi Museum, once George’s residence and the Jahaj Pul suburb in Hisar of Haryana state in India stand as reminders of his rule and his unique journey. He had earned a name for himself as one of those few European adventurers who thrived in the chaotic world of the 18th century conflict in the Indian subcontinent. He earned a series of monikers from Indians he came into contact with such as George Bahaudur (George, the gallant officer), Jowri Jung (Warlike George) and Jehazi Sahib (His Honour the Sailor). His memory lives on in Indian folklore and it has been suggested by scholars over the years that he was the inspiration for the character of Peachy Carnehan in Rudyard Kipling's story ‘The man who would be king’.

George Thomas represents an example of someone who came from nothing and reached the pinnacle of society in one short life. Born of a poor farming family in Tipperary, he moved to quarter master in the navy, to plundering raider, private subject and ended at king. His story is one of deep fascination and provides just one of many examples of the intertwined histories of Ireland and India. British intervention in India was not simply an English affair - countless stories of Irish, Scottish and Welsh integration, independence and much more on the subcontinent can be found if one knows where to look - George Thomas is but a glimpse of that connected history.

Help Ireland and the Age of Revolution grow!

This newsletter is and always will be free to access, enjoy and engage with, but it does take time and effort to create alongside my usual work routine. If you enjoy what I do here and want to see it become even better, please do consider chipping in!

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

Maurice Hennessy, The rajah from Tipperary (1971).

William Dalrymple, White Mughals: love and betrayal in eighteenth-century India (2002).

George Thomas, Military Memoirs of Mr George Thomas, (ed.) Cpt. William Franklin (1803).

The Irish Mercenary Who Became a King in India: The Extraordinary Tale of George Thomas “The Raja of Hansi” online at Brheon Academy: https://brehonacademy.org/the-irish-mercenary-who-became-a-king-in-india-the-extraordinary-tale-of-george-thomas-the-raja-of-hansi/

Allen Foster, George Thomas - The Rajah from Tipperary’, in International Journal of Anlgo-Indian Studied (2003), vol vii, no. 1, pp 39-62.

As an Irishman who has found himself stranded on the Indian subcontinent, I found this fascinating indeed. I have been meaning to explore Irish influences in Sri Lanka.

Great stuff.