On Sunday 18th June 1815, battle broke out between the allied forces under the Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley and the French army under Napoleon Bonaparte. This engagement took place in modern day Belgium near a small village known as Waterloo. It was the decisive battle in a near constant conflict which spanned more than two decades.

In the Treaty of Fontainebleau of 1814, the Allies defeated Napoleon after his disastrous Russian campaign and the protracted retreat from Moscow to France. After his abdication, they exiled Napoleon to Elba in the Mediterranean where he was allowed to keep a sizeable guard, some titles and essentially a degree respectability. He quickly grew restless, seeing what the Bourbon Restoration was doing to his realm and took things upon himself.

While the allied forces were meeting at the Congress of Vienna - deciding how to parcel out Napoleon’s Empire - he took advantage and fled Elba. He arrived back on mainland Europe on 1 March 1815 - and so began his 100 days campaign, though it was really 110 days but it just doesn’t roll off the tongue as good, does it?

Now you might be wondering why I’m harping on about the Battle of Waterloo and Napoleons demise - a military engagement known to be Napoleons last stand, Napoleon against Wellington, France against Britain. The reality is that the force Napoleon faced on that day was far more than a British one. It was a cosmopolitan collection of allied forces totalling around 68,000, over half of which were a wide array of European forces - of the remaining 23,000 troops, it was a near even split of English, Scottish and Irish soldiers.

By the close of the Napoleonic Wars, the Irish formed a significant chunk of the British army and had done for some time. Following the Penal Laws of the late 17th century, Irish Catholics were barred from entering into the military unless they converted to the established Anglican church. This limitation was eventually done away with - first informally and then officially. This was a result of pressures imposed by the American and French Revolutions. My most recent posts on the Volunteers detail this episode of Irish history in two parts, here and here.

Much like the army, the Irish population made up somewhere between 25-35% of the population on the British Isles. The easing of the laws targeting Irish Catholics, allowed the military to tap this abundant well. It became counterproductive in other words to not use this vast resource of cannon fodder right next door. Out of that cannon fodder came some martial heroes whose legacy is not dwelled on much today, but in their time they were revered.

One such hero I would like to highlight is that of Corporal James Graham. He was born in County Monaghan in 1791 - born into a generation of never ending wars. Graham like all of his brothers joined the British Army, enlisting with the 2nd Battalion of the Coldstream Guards in 1813. The Coldstream Guards offered little more than standard foot soldiers but their training was of a higher calibre and Wellington considered the NCOs (Non-Commissioned Officers) in the Guards some of the best under his command.

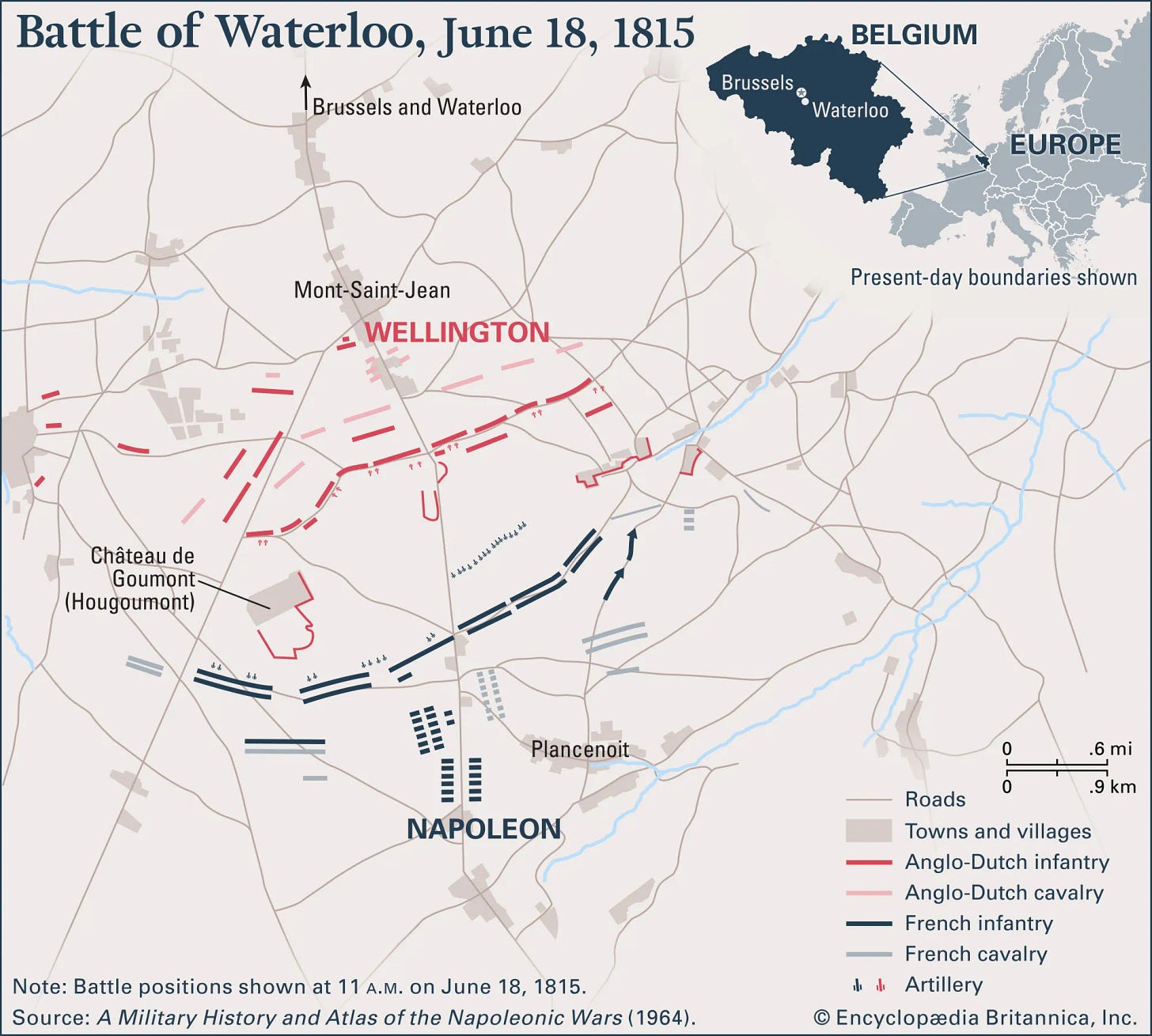

On that fateful day, the Coldstream Guards were one of the regiments located on Wellingtons right flank and they were tasked with supporting allied troops in holding the farmhouse of Hougoumont. When both the French and allied forces prepared for battle it was clear that Hougoumont would form a key strategic position. Closer to the French line, it allowed allied troops to pick off French advances and stall any offensive. If the French were to capture it - it could serve as a place for troops to organise and launch assaults against Wellingtons lines. For both parties - it was crucial.

The allied regiments embedded themselves in the farm buildings, picking out holes in the tall boundary walls to create firing opportunities and used a barn to house wounded troops. Napoleon sent regiments to attack Hougoumont to create a distraction - hoping Wellington would be forced to dedicate reserve troops to defend it, making other sections of his line weaker. The battle for Hougoumont instead had the opposite effect - it became a battle within a battle as 2000 troops fended off wave after wave of French attacks which failed to make a foothold.

At the walls of Hougoumont, the entire battle hinged on a single moment. While the stalwart defence speaks for itself, going on for nine hours - Wellington himself pinpoints the moment that saved the allied forces from defeat. The northern gate had been left open to allow for communications and supply runs but the French had managed to breach the boundaries of the farmhouse through this vulnerability. A small group of Coldstream Guards, led by Sergeant McDonnell and Corporal Graham rallied to shut the doors, against French resistance and they eventually sealed it shut. Any French soldier within the boundaries was killed apart from a young drummer boy.

Graham played a central role in this defensive move and stood on that day for his bravery. He was later commended for his not just closing the gate but also in saving a Captain Wynham from being shot by a French soldier. Later, when the building housing wounded soldiers caught fire he sought permission to leave the rank and file to rescue his brother Joseph Graham who had been wounded earlier in the day. He launched into the burning building and came out with his brother and returned to the fray.

The unique distinction offered to Graham was ‘The most valorous NCO at the battle of Waterloo selected by the Duke of Wellington’. He was also the recipient of an annuity from the Rev. John Norcross, Rector of Farmlingham in Suffolk who offered a pension of £10 annually to any solider from Waterloo named by Wellington. The Duke requested a name from the Coldstream Guards due to their crucial defence of Hougoumont and Graham’s name was put forward. The annuity only lasted two years unfortunately, as the Rector later went bankrupt.

When the same man died he left £500 to the ‘Bravest man in England’. When Wellington was asked to nominate a candidate for such a role he wrote:

'The success of the Battle of Waterloo turned on the closing of the gates [at Hougoumont]. These gates were closed in the most courageous manner at the very nick of time by the efforts of Sir James MacDonnell.'

MacDonnell was Grahams commanding officer so the decision was sensible - but once awarded the prize, MacDonnell subsequently awarded half of the share to Graham in recognition of his brave assistance.

Graham, like many Irish veterans of the Napoleonic Wars, lived out the last 15 years of his life in the Royal Hospital Kilmainham as an in-pensioner after leaving the army on grounds of poor health. He would die there in 1845 and his memory lives on by way of a plaque erected in his honour - highlighting his deeds on 18th June with the dispatch sent that day reading:

‘Graham assisted Lieutenant-Colonel MacDonnell in closing the gates, which had been left open for the purposes of communication, and which the enemy were in the act of forcing. His brother, a Corporal in the Regiment, was lying wounded in a barn, which was on fire, and graham removed him so as to be secure from the fire, and then returned to his duty’.

Grahams story is one of many Irishmen who served in the British army and is one who perhaps is neglected more than others for his willing participation in the army. Dan Harvey’s book, A Bloody Day: The Irish At Waterloo is a fascinating read which shed new light, on a largely untold story. We forget how many Irishmen took up roles in the British forces in the late eighteenth, early-nineteenth centuries. It became tradition for some, a means to an end for others.

It is something I think we need to tackle and to come to grips with. Their stories should be no less valuable than Irishmen who fought for independence and separation. Taking the kings shilling as it were should not negate those of the past to the field of ignorance when considering history - everybody has a story to tell. After the Act of Union, many wholeheartedly entered into the enterprise of empire and imperialism - and they tell the story of Ireland and Empire as much as any other. A story I have endeavoured to tell in previous posts, and strive to continue to shed light on going forward.

Further Reading:

Dan Harvey, A Bloody Day: The Irish at Waterloo (Dublin, 2017).

Richard Holmes, Wellington: The Iron Duke (London, 2003).

Gripping tales, Ruairi, and very interesting.