'Silent Participants' of Empire: the O'Rourke sisters of Saint-Domingue, Nantes and Wexford, 1788-1805.

The history of the eighteenth and nineteenth century has for a long time been a very top down affair - ‘great men’ history, high politics and big events took the focus. It is only in recent decades that we are getting decent and much needed re-analyses of other aspects of society, politics and culture. More recently, we are being given re-appraisals of complicated and divisive histories surrounding slavery and the role of the disadvantaged and marginalized in society.

Today I want to look at the story of the O’Rourke family - and more specifically the women in that family. Orla Power, historian of Irish-Atlantic history, in her chapter about this topic, the primary reading for today’s post - takes us through the painfully tragic story of their lives. The events that shape it, affect the lives of the entire family - men, women and children - but the ability of some to escape that destitution brings into stark contrast the differences in gender in the late eighteenth century.

The story of this family illustrates the complicated way in which some Catholic Irish families interacted with empire, be it French or British. Many Irish catholic families fled Ireland in the eighteenth century as a result of the Penal Laws and in their new homes, many became merchants and established strong trading businesses. Naturally, many found themselves deeply involved in the trading of human cargo to the West Indies at this time.

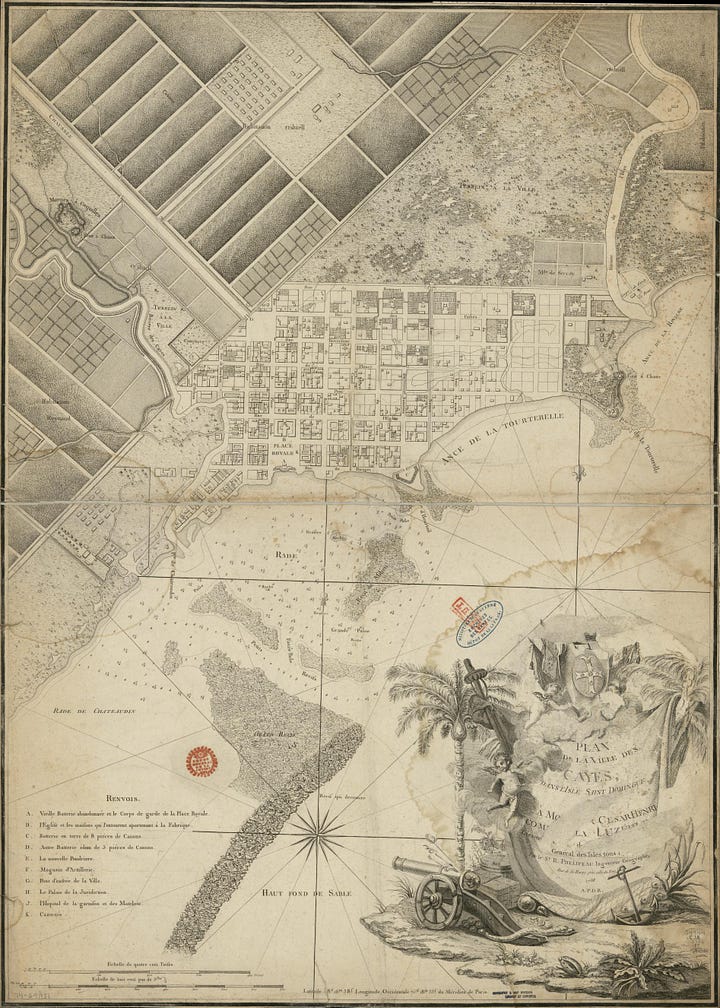

Two brothers, Patrick and Edward O’Rourke established themselves on the island of Saint-Domingue (modern day Haiti) in the port of Les Cayes on the southern coast. This was after a long time spent in Nantes in north-western France until they received naturalisation papers and were able to establish themselves in the colonies. Edward and his wife Marie (Roche) had five children together in the early 1780s but tragedy struck when Edward died at the young age of 44 in 1783 leaving behind Marie to raise five children under 5 years of age and manage the plantation alongside it - all of which she excelled at.

Unfortunately tragedy would strike the family twice again before the decade was out - in early 1788 the oldest son Louis passed away at the age of 9, and subsequently later that year, Marie herself fell ill and passed. This left behind four children, all under the age of 10 now, to be cared for under the guardianship of their uncle Patrick.

In 1789 the remaining children of Edward and Marie O’Rourke - Patrick, Renée, Françoise and Marie were sent back to France to receive a proper education in Nantes. The world they stepped into was one on the brink of collapse as the Bastille was stormed on July 14th and the French Revolution had begun. With the new ideals of the revolution - liberty, equality and fraternity - pouring out of France and on to the colonies, it undermined colonial authority when it became clear that such ideals were not intended for the slave populations.

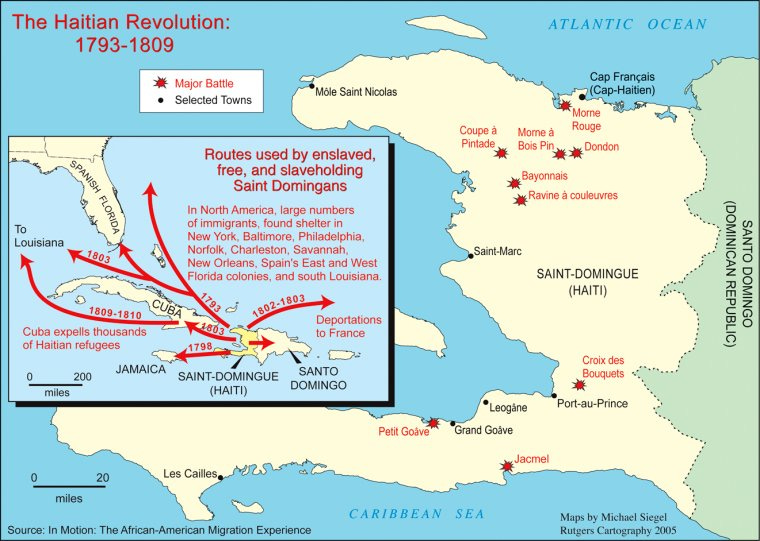

The demographics of Saint Domingue are startling at this time - by 1780 the population of the colony was about 500,000, only about 40,000 were white settlers of all backgrounds, rich and poor, government officials and planters. In addition to this there were around 30,000 freed people of colour occupying the middle classes - the remainder, c. 430,000 belonged to the enslaved classes of the island.

By 1791 infighting served to divide the white population of Saint Domingue and a sizeable chunk of the free people of colour began to demand equal rights - talk of murder and intimidation became common. In August of that year, a bout of looting, burning and killing erupted in the northern province of the colony, destroying 1,000 plantations. It is around this time that the figure of Toussaint Louverture began his rise to power and the non-white population begun to organise in earnest.

As a result of the upheaval, the sugar trade from the island was disrupted immensely and while the O’Rourke children’s plantation remained unaffected, the processing of sugarcane slowed, and the ability to ship sugar to France became challenging. The result was a dwindling in the revenue making its way to the children. Until this point their uncle Patrick had been assisting with their funds but he now found himself struggling to support his own family, and eventually making the difficult decision to flee the island himself.

While in France, the children were being cared for by servants in the employ of their uncle - but seeing the way the wind was blowing, and the revenue stream drying up, they terminated their contract of employment. This ultimately left the children orphaned and homeless, in a country they didn’t know, with nobody to look after them and at a time of political and social turmoil.

The only alternative for the children was to go to Ireland, and stay with the family of their mother, the Roche’s in Wexford. Something which deeply troubled their uncle Patrick after the introduction of the new law in France which ‘colonial landowners are subjected to, [it] states that their residence must be in France. This concerns me as these unfortunate children may not be entitled to claim what is theirs’.

Similarly, Patrick O’Rourke and his family had made their way from Saint Domingue back to Nantes and then decided to flee to Baltimore, Maryland - a place renowned for its Irish community, and a port city which the O'Rourkes had traded extensively with during their time in the Caribbean. Many of those fleeing Saint Domingue, were refugees of a political crisis - temporarily (at first) displaced from their homes and forced to seek refuge in neutral ports, many of them in America (Click here for an article about how many fled to New Orleans). Initially, these refugees depended on the kindness of locals, charitable donations and such to get by and eventually government aid was forthcoming when it became evident that their short stay would be rather long.

Returning to the children - by 1796, they had been in Wexford for four years and had yet to receive any further support from their uncle Patrick. To support the Wexford family and the O’Rourke children, the father of the house, Edmund Roche was forced to join the Yeomanry - becoming a reserve member of the British forces in Ireland. Alongside this, all of the children had begun contributing financially to the household in whatever way they could - the girls by giving piano lessons or making dresses.

The only boy, Patrick, had much more freedom in his pursuits for money, and embarked on a much more lucrative and viable career in the army. He was able to find a sponsorship through a network of familial connections in both the British and Austrian military and got his commission as an officer in late 1794. He was to return to his home of Saint Domingue in 1796 - he wrote to his Uncle Patrick;

‘You will be without doubt astonished to learn that I am close to you. By the time this letter gets to you I will be in the Bahamas…I am a lieutenant and I also have hope to advance three or four ranks…’

For the girls, the outlook was not good. As young women of their class - options were limited and their entire identity and future depended on them returning to their plantation - their entire upbringing and ability to make it anywhere in life depended on the continuation of the plantocracy into which they were born.

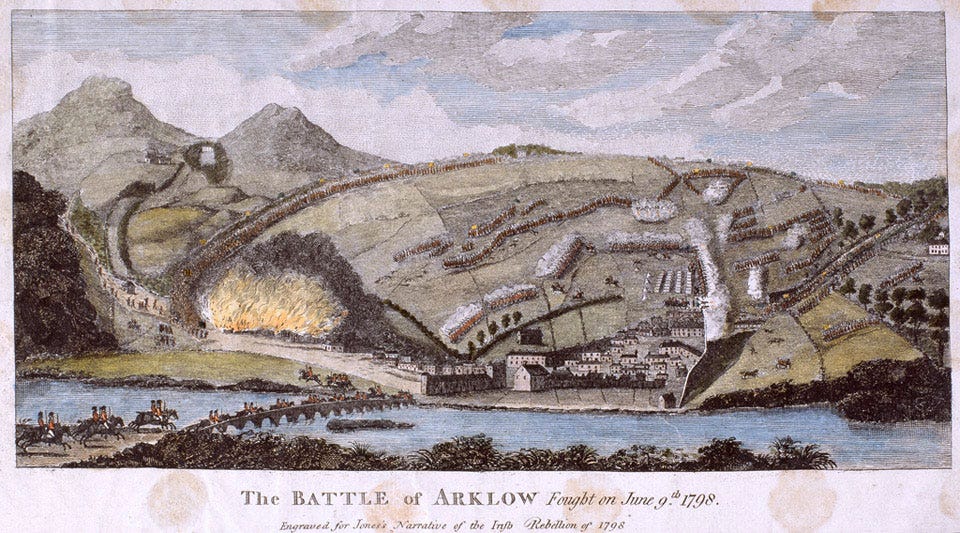

By 1798, the sisters were yet again forced to relocate - with the outbreak of the United Irish Rebellion that summer, it was considered too unsafe to remain. This was particularly true because of Edmund’s position in the Yeomanry and their brother being commissioned in the British military, things that could have made them legitimate targets of reprisals.

The sisters fled first to Dublin and then on to London where they joined a burgeoning community of French exiles – planters, merchants and politicians who all had vested interests in the situation of Saint Domingue. Power discusses how this can be seen in the language used by them in correspondence to their Uncle Patrick. Their understanding of the political and commercial affairs of the island, and closely following the progress of a the British Expeditionary force – ‘The news from Saint-Domingue continues to nourish our hopes of a favourable outcome’.

Moving to London must have been a great thing for the sisters. In Ireland they seemed to have felt out of place, they knew nobody, the language and culture was dramatically different to their own. As Power states in her essay, ‘fallen from a previous life of grandeur, they felt as though they were the objects of pity’. In London, they found many people in the same situation as them, while their resources were meager, the wider émigré community supported those who needed it.

They found work making straw hats, but like the dressmaking in Wexford, the money remained little – they relied on their brother Edward to sustain them with his military wages;

‘He is a great support to us here even though he is so young. We have had moments where he has had the strength to support us in times of trouble’.

The sisters remained dependent on their Uncle Patrick also, for a lifeline in regards to their plantation. He remained unable to visit the island, much to their frustration. Ill health and an unstable political situation made it difficult for him to return to the Caribbean until 1799. British forces in 1798 unexpectedly withdrew, leaving it in French control and split among revolutionary groups – creating a sort of stability not seen in recent years. It is in this political climate that Patrick returned. Marie wrote, in April 1799;

‘letters that have recently arrived say that things have taken a turn for the better, that Toussaint Louverture still welcomes whites and they are allowed without exception to return to their property’.

When they received letters from their uncle during his time in Saint Domingue however, it became clear that things were not good, and their return, was unlikely to ever materialise;

‘I was on my plantation suspecting nothing when the fires started all over…I hid my religious artefacts with care in case they would inspire an angry reaction…I then asked to be taken to the village to avoid being massacred like all the other unfortunates who were killed when they were least expecting it. With the arrival of the French here, it was hoped that all the obstacles would be removed and that the land owners would be allowed to return to their properties. Instead, the difficulties have multiplied…’

Patrick never gave up hope that he would be able to take back his plantation on the island. In his final letter to the sisters he said ‘I do not want to give up hope because I still have the smallest hope that I can be useful to you’. The sisters never sent a reply back to their uncle.

Many of those settlers who returned to the island, under the impression that they could reclaim their property were frustrated at every corner – many in fact, were killed in the process. Edward, the only son and legal inheritor to the family plantation never made an effort to return, accepting that it was lost after the ratification of the Haitian constitution in 1805 declaring formal independence, abolishing slavery on the island permanently, and making clear that former white settlers were no longer welcome.

Patrick viewed the silence from the sisters Marie, Françoise and Renée as obstinate indifference to his own well-being, in reality it seems to have been much worse than that. He clearly failed to understand how much their lives and identities were entwined in the future of plantation life. All three of them died within months of one another shortly after the declaration of Haitian independence in 1805 - none of them lived beyond 30 years old, bringing in to focus their destitution in their final years.

Marie, Françoise and Renée O’Rourke all benefited directly from the slave and sugar trade but Power argues that just as much they were victims of a system predicated upon a patriarchal structure. Contrasted with the outcome of their brother Edward, we can see that the sisters were victims of a system which stifled the lives of the women within it - ‘In spite of their class, education, family network and their personal connections. These women found themselves unmarried, penniless and stateless’.

The Irish Atlantic world is a deeply fascinating one to venture into and a terribly under explored one. We often try to separate Irish people from the imperial framework, highlighting primarily the victim-hood of the Irish, and rightly so - but as Dr Ciaran O’Neill of Trinity College, Dublin said in a recent episode of Talking History; 'It's not fair of us to decry the colonisation of Ireland, as we do quite rightly in Irish history and then write out our part in the colonisation of others'. If the general history remains an under explored history, it is even more true of the stories of the traditionally under-represented.

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

Orla Power, ‘Stateless and Destitute: The O’Rourke Family of Saint Domingue, Nantes and Wexford, 1788-1805’ in Daniel Sanjiv Roberts and Jonathan Jeffrey Wright (eds), Ireland’s Imperial Connections, 1775-1947 (Palgrave, 2019).

Nini Rodgers, Ireland, Slavery and Anti-Slavery 1612-1865 (Palgrave, 2007)

Kirsty Carpenter, ‘The Novelty of the French Émigrés in London in the 1790s’, in Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick (eds), A History of the French in London: Liberty, Equality, Opportunity (London, 2013).