On a crisp and cool evening in early July 1867 the steamboat G.A. Thompson chugged its way down the Missouri River, towards Camp Cooke. As a lone sentry patrolled the upper decks, he spotted in the corner of his eye a man hastily making for the rear of the boat, dressed in nothing but his underclothes. Thinking it an officer going to relieve himself over the edge, the sentry turned and moved on to provide some privacy. Suddenly there was a yelp and a loud splash - extensive searches were made of the water, to little avail.

The weak light provided by their lanterns barely illuminated the water beyond five feet. No calls for help could be heard - only low and agonising cries. At dawn, there remained no sign of the person who went overboard. To this day there is still an aura of mystery shrouded over the missing body of Thomas Francis Meagher. Speculation still divides scholars over the nature of his death - did he simply trip and fall or were there more sinister games being played in Montana politics - was he pushed to his death?

After the close of the Civil War Meagher was wanting for opportunities and work. He wanted a political appointment which would allow him to revitalize his mixed reputation of the Civil War years. Following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln early in his second term - Andrew Johnson of the Democratic Party assumed the role. Meagher, a long-time supporter of the Democrats, harried and begged for an appointment from the administration.

Eventually Johnson relented and offered Meagher the role of Secretary of the Montana Territory. In reality Meagher had hoped for the Governorship but Johnson feared that the appointment of a Democrat to the role, so soon after the Civil War would stoke unwarranted hostility from the Republican led Congress.

Jon Axline gives a great overview of Meaghers time in Montana;

‘Few figures in Montana’s short history have continued to generate as much controversy as Thomas Francis Meagher. Arriving in the territory with the best intentions, he clearly left it in a worse condition than he had found it. Like many Americans, Meagher viewed the West as a land of opportunity, a region that would give him a chance to revitalize his sinking post-Civil War military and political career…Positive that unlimited possibilities for personal advancement lay before him, Meagher tackled his new position with the characteristic enthusiasm and bravado that had marked his Civil War career. His activities in Montana, however, would create powerful political enemies. Their deep-felt personal hostility would help discredit him in contemporary eyes as well as continuing to influence any assessment of Meagher in our present century.’

In September 1865 following his appointment - Meagher arrived in Montana and stepped into a divided and volatile political maelstrom. The situation in Montana was held together by a political system whereby most of those elected, represented the Democrats but were controlled by federally appointed Republicans.

Prior to his arrival the Republican governor had taken away the territories right to hold a legislative assembly, with the governors son calling them ‘rebels and traitors’, who were ‘unfit to exercise the right of self-government’ in light of recent events. In the eyes of the Republican minority - it was better to have no government at all, than one they could not easily control.

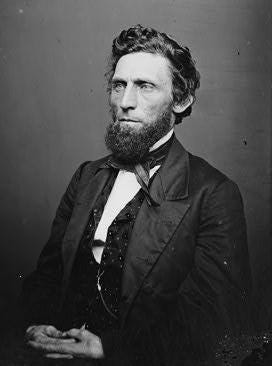

As soon as Meagher arrived in the territorial capital of Bannack, Governor Sidney Edgerton - who was deeply unhappy about Meagher’s appointment - returned to Ohio, making Meagher acting governor. He was introduced initially to the leading Republican members of the territorial government who got in his ear about the state of affairs in Montana. As a Union Democrat, he sympathised with much of the concerns the Republicans had for their counterparts, he believed they were ‘turbulent men…favourers and abettors of treason’, men ‘not fitted to govern’. Meagher was determined to forge his own path, as his own man without connection to either party and would struggle in the coming years to maintain the interests of both factions.

As time went by, Meagher’s sympathies shifted significantly towards the elected Democratic majority. He came to feel that the Republicans exercised more control of the territory than their positions warranted – impeding his own ability to perform his role as acting Governor. It may have helped, Axline comments, that many of the Democratic majority were themselves of Irish or Irish American descent, creating a common bond and he would come to be seen as a spokesman for the Democrats in Montana.

The final break with the Republicans came for Meagher when he decided to recall the legislative assembly and reform the government. They claimed that he had no right as acting governor to make that choice and that he was severely over stepping his bounds. Further to this, he called for a constitutional convention to take place to begin the process of drawing up a constitution, the first step in the journey towards statehood. It was claimed by one of his strongest rivals that the only reason he sought a constitutional convention and statehood was because he surrounded himself with flatters and soothsayers who promised Meagher a seat in the senate for their newly formed state.

In July 1866, any authority which Meagher held as acting-Governor was shattered when Andrew Johnson replaced Sidney Edgerton the governor of the territory who had been absent since welcoming Meagher. He was replaced with Green Clay Smith – a Mexican War veteran, Union Major General from the Civil War and former congressman. Meagher, in response attempted to resign from his post as Territorial Secretary, but Smith had convinced him to remain – the two it appears had a genuine respect for one another.

Like Edgerton, Smith didn’t stay in Montana for long, seeking a leave of absence in January 1867 – Meagher yet again found himself filling the boots of acting-Governor. While the political atmosphere largely settled under Smiths short time in office, matters immediately deteriorated upon his departure. It is during this time, that two of Meagher’s fiercest opponents found themselves in Washington D.C. and lobbied the Republican Congress to make null and void any legislation put forth by Meagher and his recalled legislative assembly the previous year.

Meagher’s career as a politician seems to have come crashing down definitively at this point. Johnson made the decision to replace Meagher as Territorial Secretary, taking away any powers he held. The Congress agreed to the requests of his rivals and with it, any progress he made in the territory was reversed – it was as if he was never in charge at all, apart from the polarisation of politics his time generated.

He was able to put a positive spin on this change however – he determined that he was not destined to be a politician but rather, he was to be an accomplished military leader and earn his reputation on the field of battle – though his Civil War record and how he is remembered for his role would beg to differ. He sought to make a name for himself as a soldier in the ongoing war with local native Americans in the Montana region, specifically against the Lakota and Cheyenne. Since 1866 the two groups had come into constant conflict with the US Army, besieging three forts in south-central Montana for nearly a year continuously.

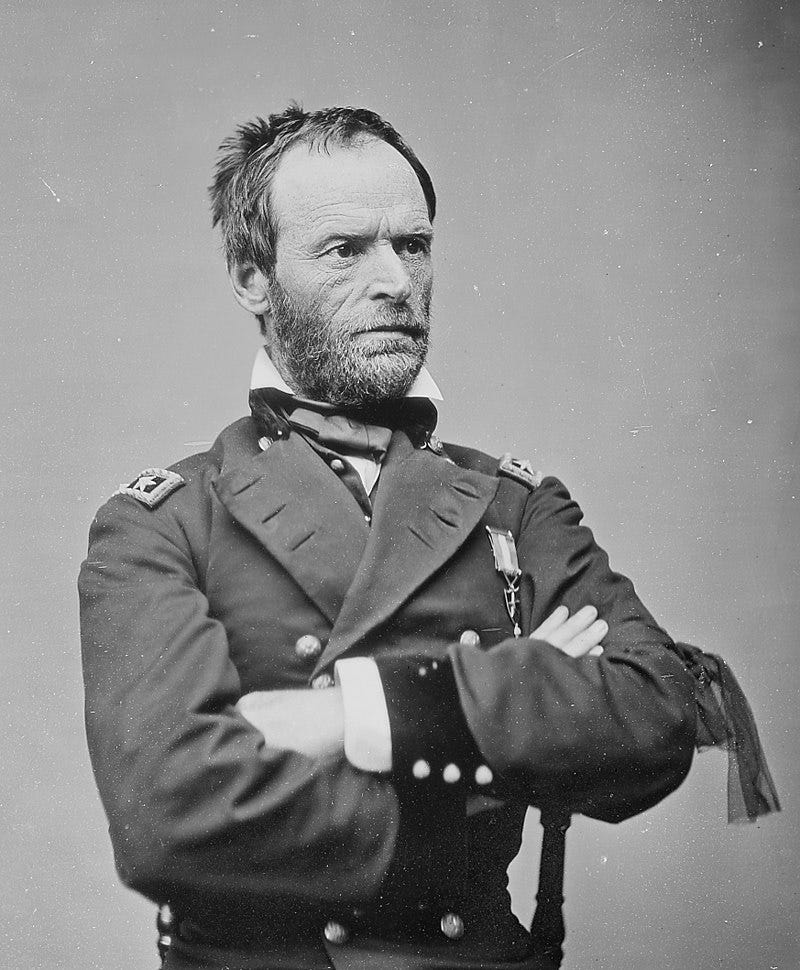

Since his arrival in 1865, Meagher had been continuously petitioning General William Sherman – commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi – for military assistance in the territory in order to safe guard settlements against Native American incursions. He never received any, in fact barely received a reply at all. In February 1866, Sherman wrote to him;

‘I have received your several letters…on the subject of troops for Montana and routes leading thereto – until Congress fixes the establishment it is idle for us to calculate what proportion of troops can be assigned to nay part. Were I to grant one tenth the part of the calls on me from Montana to Texas I would have to call for one hundred thousand men, whereas I doubt if I should expect to have ten thousand men in all’.

Meagher eventually received permission from Sherman to form a territorial militia comprised of local residents willing and able to take up arms to defend themselves. It must be noted however that the militia he formed was a far cry from the Irish Brigade of the Civil War – it did not maintain the same enthusiasm and desire for glory, the cause was not a righteous on in the eyes of those involved. Instead, they were ‘a motley collection of businessmen, former vigilantes, lawmen, miners, bullwhackers and frontier ne’er-do-wells’ who spent ‘most of their times fighting themselves over rank, deserting or drinking’.

In the end the militia never even took to the field against the native Americans and Meagher never achieved the glory he so desperately sought. Realistically, Axline states that the militia was more ‘like a summer camp for the recalcitrant’ and that ‘Meagher seemed more interested in the adventure and glory than in the drudgery of commanding troops’.

In June 1867, Meagher and eleven officers from the militia set out to collect a shipment of weapons from Fort Benton, sent upriver by Sherman. While making the journey Meagher had fallen ill with dysentery due to the scorching heat and long days riding – the trip was delayed by 6 full days while he recovered. They eventually made it to Fort Benton on 1 July, exhausted both physically and mentally, Meagher sought refuge in the backroom of a log store next to the river.

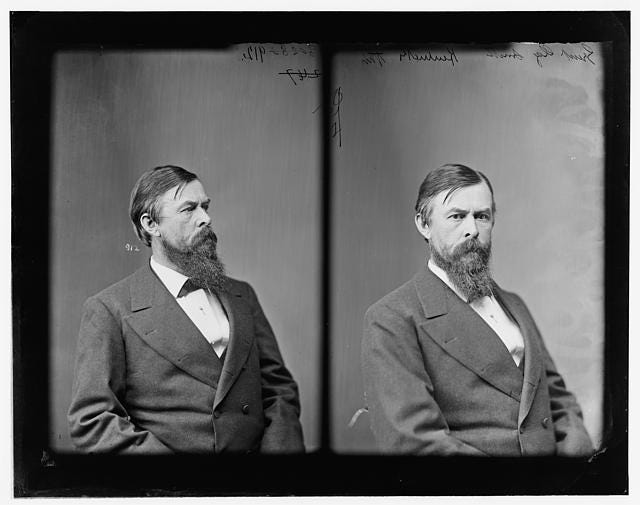

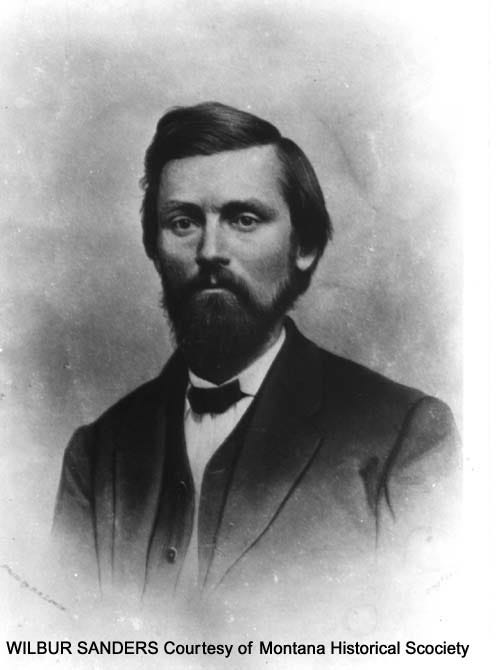

It is while in this store, that Meagher learned that the shipment had never even made it to Fort Benton but instead was 130 miles downriver at Camp Cooke – the river water was too low for the boat to make the full journey – certainly news he was less than happy to hear. Instead of making the journey over land again, the decision was made to travel by river on the steamboat G.A. Thompson. One of Meagher’s strongest rivals from his time as acting governor was also in town, and also travelling down river of the steamboat – Wilbur Fisk Sanders. He noted;

‘My attention was arrested by abnormally loud conversation, and as the party came nearer, I saw that it came from General Meagher. As the party came to the place where I was, it was apparent that he was deranged. He was loudly demanding a revolver to defend himself against the citizens of Fort Benton, who, in his disturbed mental condition, he declared were hostile to him’.

This is but one account which speaks of the distress which Meagher found himself in shortly before leaving Benton. According to the pilot of the boat, Meagher overheard someone earlier in the day say ‘There he goes’, insinuating the comment as a threat and also claiming that his life had been threatened during his stay in the settlement. Both Doran, the boat pilot and Sanders agreed that the general was not in his right mind that evening. It is later this evening, after Meagher finally calmed down and retired to his room, that we come back to the beginning of today’s post – the figure seen running to the rear of the boat, was Meagher. Some men dropped into the water while others ran downstream along the shore, despite their efforts, Meagher was never rescued and the body, never found.

There still remains some debate as to how Meagher fell – was it an accident? Or an act of malice from a political opponent? There is some case to suggest it was a targeted assault/assassination though it is all circumstantial in nature. The amount of controversy and hatred he managed to drum up from his enemies in such a short time make the possibility of assassination somewhat reasonable. Many local Irishmen claimed that Meagher was a victim of tribal politics – North and South, Democrat and Republican, nativist and immigrant – and many held the belief that he was pushed overboard that night. Meagher was, ‘of the wrong party, the wrong church and was far too vocal in his opposition to the status quo of Montana’.

This is further reinforced by the claim some half century later by Frank Diamond who claimed to have killed Meagher in exchange for $8,000 offered by a Montana vigilante group, though he later revoked this confession. This could perhaps explain some of the delusions Meagher was suffering? Or perhaps they weren’t delusions, perhaps threats were indeed made against his life, and just maybe, those threats were acted upon.

The more likely, and plausible scenario though, is such – he likely went on deck to relieve himself because he was still suffering from dysentery, an illness of which the main symptom is diarrhea. Being unwell and unsteady on his feet and quite clearly suffering delusions of some sort (perhaps from a fever, though there is no document of this) he could have lost his footing and hit his head on the way down. This particular fits the bill when taken into account the likelihood of ropes lying around the deck, and on this particular boat, the railings usually encircling the upper decks for safety had been removed following a collision only a few days before, leaving Meagher nothing to balance himself with or hold on to.

His death remains one of Montana’s most enduring mysteries – there are more likely theories than others, but all of them remain theories alone. In his two years in Montana, he had managed to hold the role of acting governor for much of it, attempted to reinforce the democratic process for the majority, and attempted to put the territory on the path to statehood. Failing this he attempted to reassert his military reputation against the native Americans. Sadly, also failing this, Meagher died in 1867 at the young age of 44 leaving behind an incredibly mixed and somewhat deflated legacy.

Naturally, people prefer to remember him as a courageous Irish patriot, idealist and renowned orator and the commander of the Irish Brigade in the American Civil War. To this day, in Montana, Meagher remains one of the most debated politicians and historical figures – there remains, after 140 years almost no middle ground as to the interpretation of his character. In Ireland he is remembered for his role in the Young Ireland movement and subsequent rebellion of 1848 – in American and Montana, he cuts a much more complex figure. He is remembered in both Waterford, Ireland and Helena, Montana with equestrian statues - Waterford his home town, and in front of the State Capitol of Montana.

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

John M. Hearne and Rory T. Cornish (Eds), Thomas Francis Meagher; the Making of an Irish American (Dublin, 2006).

E.P. Cunningham, Thomas Francis Meagher - Dictionary of Irish Biography entry.

Timothy Egan, The Immortal Irishman: The Irish Revolutionary Who Became an American Hero (2016).

This was great! I am from Montana and had no idea Meagher died in my home state.