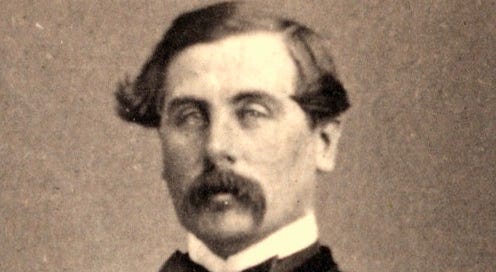

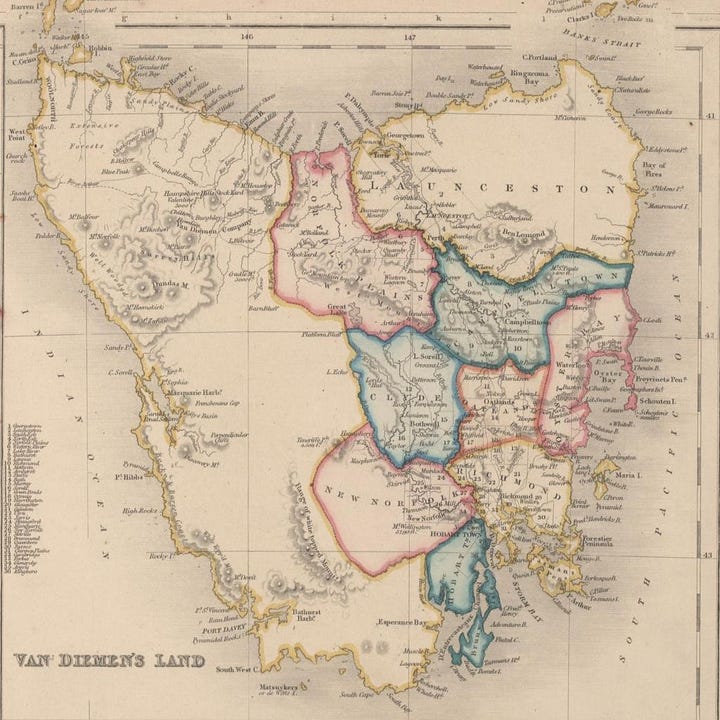

In January of 1852, Thomas Francis Meagher was whisked away from his exile in Van Dieman’s Land, modern day Tasmania, to New York City to join the significant Irish exile community and an even larger Irish-American community. Irish-Americans created the single largest ethnic minority group in New York – roughly 25%.

The British authorities largely ignored the escape of Meagher to America but one Irish Nationalist newspaper proclaimed, ‘Meagher in America: what a triumph…we conceive a great career for him under the flag of Washington’. Following his escape, he changed his name to O’Meagher in an attempt to extol the memory of previously exiled ancestors from the Williamite Wars and Fontenoy in 1745.

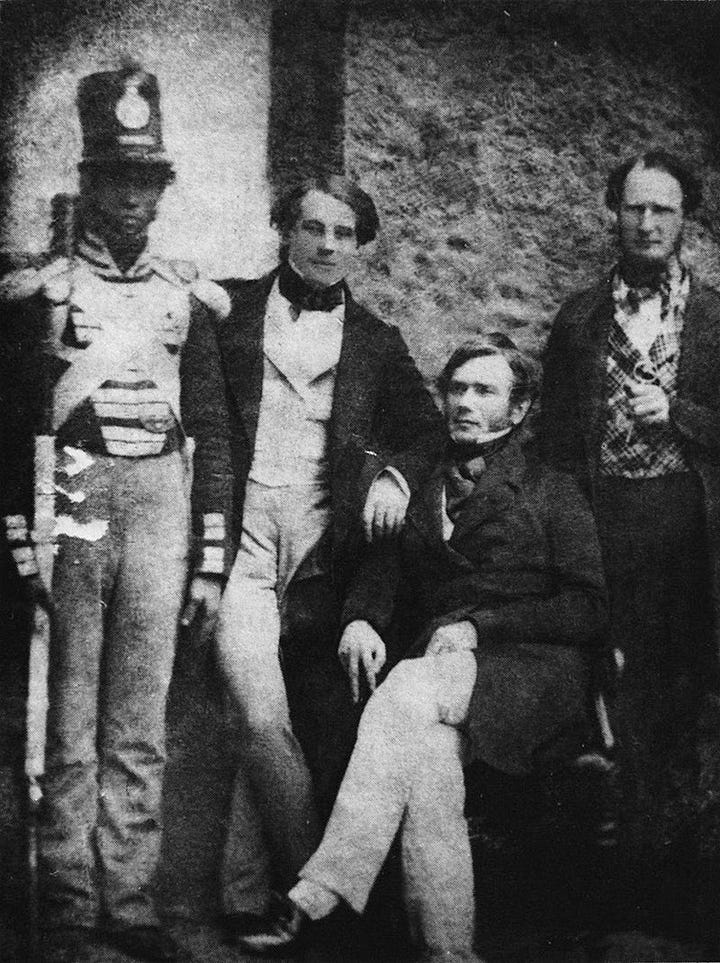

Meagher’s old friend and colleague John Mitchel joined him in New York not long after – following much the same route of escape. The two exiles approached life in America very differently however. Mitchel, as stubborn as resolute as ever refused to dilute his political beliefs – maintaining a controversial reputation as a radical revolutionary. When both men arrived, they were met with criticism from the church in America and conservative Irish-American opinion.

Meagher learned the language of moderation and caution in order to navigate this new environment and kept his more radical opinions to himself – his aim was assimilation. Mitchel chose another route entirely. Both men would go on to play important roles in Antebellum and Civil War America, both for opposing sides. Mitchel would later move to Tennessee and write for the Southern States – Meagher, while supporting of the Democratic cause and neutral on slavery, volunteered for the Republicans and the defence of the Union when the time came.

Over the course of the 1850s Meagher attempted to break into a number of careers; newspaper publisher, lawyer, public speaker, social celebrity. Not long after he arrived, in 1853, he embarked upon his first speaking tour which took him across much of New England and a number of Southern cities – including Charleston and New Orleans. Following its completion in August 1853 his speeches were collected and published in the form of a book. The combination of this book and his speaking tour served to establish his credentials as a leading Irish spokesman in America.

Rory T. Cornish highlights that while Meagher’s fondness for America grew, his old life – his family and friends – began to take a backseat and he began to either grow weary of those connections or lose interest altogether. When in 1853 after his tour concluded, his father Thomas Meagher Jr. and wife Catherine Bennett Meagher came to visit him – he cut the visit short as soon as he had the excuse. The California Steamship Company offered him a free visit to San Francisco. His wife would return to Waterford and give birth to the couples only son and just a year later Catherine died – an event which seems to have impacted Meagher, very little. Along with this, Meagher did his best to distance himself from his long-time friend John Mitchel and his radical views.

The death of Catherine simply served to adjust Meagher’s focus to a new career – leading to a new marriage to Elizabeth Townsend, daughter to the owner of the New York Sterling Ironworks making Meagher a member of upper-class New York society. Alongside this, in 1855 he was encouraged to return to his original profession, that of the law. He was midway through his education in the 1840s when he abandoned the profession of politics. Now under the guidance of Judge Charles Patrick Daly and tutored by Judge Robert Emmet, nephew of that Emmet who led the rebellion of 1803. Successfully passing the bar in 1855 Meagher set up a practice which was easy, to maintain a successful law office was the hard part – something he found tedious and supplemented with further speaking tours.

In 1856 he established the Irish News, which openly supported the Democratic Party, maintained a pro-Southern outlook and was politically neutral on the question of slavery. It in other words, reflected the outlook of the New York Democrats who believed that sectional differences between North and South were not worth destroying the Union. They were in many respects the moderate voice of the Democratic party.

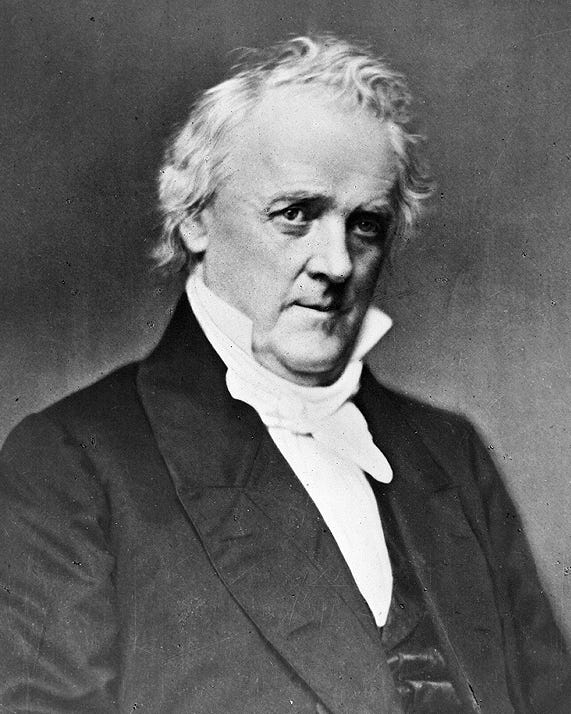

At the close of the 1850s, having received his citizenship and failing to get a political appointment from the Democratic president James Buchanan – Meagher ventured to Central America with Elizabeth to explore financial opportunities such as the development of a railway. While abroad, Abraham Lincoln the Republican nominee for the 1860 election became the newly elected president. Upon their return to New York City, the country was hanging by a thread on the precipice of war.

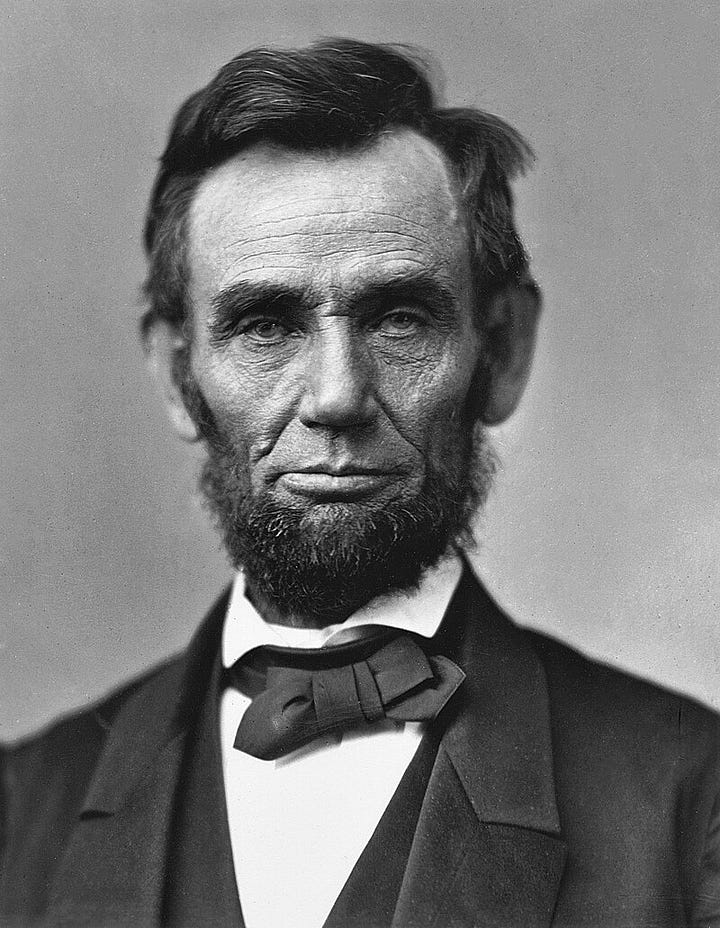

The election of Abraham Lincoln had surprised Meagher. He ran on a platform which advocated for no further expansion of the institution of slavery into the western territories. His election was enough for a number of southern states to formally secede from the Union in 1860. A year later, with the refusal of federal troops to leave Fort Sumter in South Carolina an assault on the fort was led by Confederate forces – sparking the beginning of the conflict between North and South, the American Civil War.

Upon hearing the news from Sumter, Lincoln called for the formation of an army of 75,000 volunteers – an action which prompted more southern states to secede from the Union. In all, 11 of the 33 states broke away from the Union. Many Irish-Americans fought for both sides during the conflict, many for reasons of politics and ideology – but just as many fought for their given sides, simply because of geography and which side of the divide they ended up on.

On 22 April 1860, Meagher made the decision to volunteer for the Union – being commissioned as a Captain of a New York militia company. His choice to fight for the Union has garnered criticism from biographers and historians alike – claiming that he held inconsistent views and beliefs when it came to republicanism and politics. To some, his decision to support the North was an

‘abrupt turn of events and a seeming betrayal of a lifetime of resistance against central authority’.

Cornish makes clear though, that

‘Meagher never opposed central authority, he opposed arbitrary authority – a government which ignored the freedoms and rights of the governed’.

As a matter of fact, he remained steadfast in his support for the Democrats. He expressed his belief that one could maintain a more nuanced outlook than simply right or wrong, north or south. Acknowledging the legitimate election of Lincoln, and his displeasure at the secession of the south, Meagher said he could not find ‘one substantial reason or pretext for the revolution’, and placed the outbreak of the Civil War at the feet of ‘self-interested, hot-headed southerners, especially those in South Carolina’.

In comparing the liberties available to southerners, to the state of Ireland in the first half of the nineteenth century Meagher argued that he would not have ended up a revolutionary, let alone in exile;

‘Had Ireland been under the enjoyment of such privileges and such rights, and such a guaranteed independence as South Carolina enjoyed, I would not have been here tonight, the scaffold would not have been stained with one drop of martyrs’ blood, and Ireland would have been spared many a generation of martyrs and exiles’.

Meagher joined the Union in an effort to preserve what he thought magnificent, the freedoms granted to all by the constitution of the United States. The revolt of the South for ‘independence’ was, in his eyes, ‘unjustified and treacherous’ and could not be compared to the revolutions of 1848. With this in mind – Meagher joined the Union forces in Virginia in May 1861. He an his unit fought at the wars first major engagement, the Battle of Bull Run – a route for the Union forces, and an engagement where Meagher had little impact.

He was later made Captain within the regular United States military and was shortly after promoted to colonel of the 69th New York Infantry - a unit later labelled ‘the fighting Irish’ - though he barely even took command as he had designs on creating an Irish Brigade, one which could evoke the memory of the Wild Geese who fought in the Irish Brigades of France and Spain.

In November 1861 such a brigade was formed with Meagher as its commanding office – though not officially under February 1862 when he was commissioned Brigadier-General in the US Army. He commanded the brigade for about eighteen months, February 1862 to May 1863, in all in continuous, active service – playing important roles in all major engagements of the period – Malvern Hill, Antietam, Fredericksburg. By December 1862, the brigade had been worn down from 3,000 troops to a mere 500 suffering heavy casualties in all engagements.

History has not been kind to Meagher’s military record as the brigades first commander. Some historians and contemporaries alike looked to his abuse of alcohol and desire for personal glory as the reason for such high casualties but there is another side to this coin. The Irish Brigade held a reputation for ferocity in battle – it did sustain heavy casualties but this was largely due to the fact that it was viewed as a strong combat unit, often thrown into the meat-grinder at key moments to turn the tide. As Cornish highlights,

‘Meagher alone cannot be blamed for this as he was, of course, required to follow the orders of his superior officers’.

He in fact argued for the unit to be cashiered to allow for replenishment and to give those remaining a break from the war – after this request was refused, Meagher handed in his resignation in May 1863.

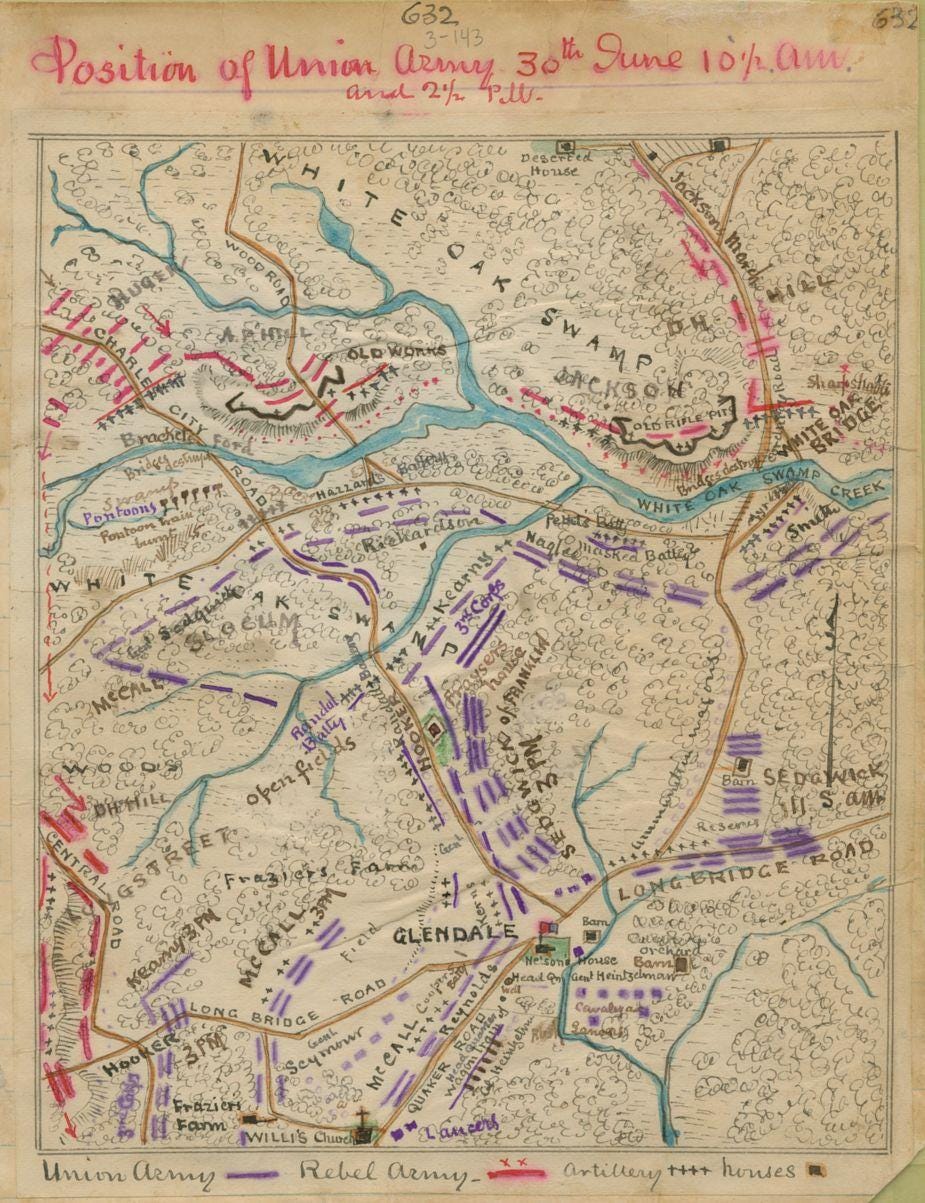

Even after this, it should be noted, the brigade continued to suffer unusually high casualty rates – further bolstering Cornish’s point that Meagher can not and should not be blamed. Despite having no military background, he made a name for himself with his bravery, always leading from the front. Many of the officers under his command had been veterans of other European wars – they never questioned his personal bravery and were saddened by his decision to resign. At the Battle of White Oak Swamp, 30 June 1862 – Meagher was spotted riding up and down the line oblivious to any danger despite being under intense fire from Confederate forces. When asked to get down he refused, ‘No I will not dismount. If I am killed, I would rather be riding this horse than lying down’.

After his resignation, Meagher no longer played an important role in the war and never came into contact with the Irish Brigade again. He briefly took control of a rear-guard garrison in Tennessee but bungled a transfer of troops and was relieved of command. He emerged from the war with a mixed reputation – in his DIB entry, E.P. Cunningham points out that he was remembered as ‘brave, eloquent, convivial, inspiring; skill or effectiveness as a commander are not mentioned by contemporaries’.

In fifteen years, Thomas Francis Meagher had managed to do a lot towards making a name for himself not just within the Irish American community but in the wider American political community. He rose from an exiled republican to a member of New York’s high society, to the creator and first commander of one of the Unions most ferocious and effective brigades. He was ‘important and controversial…vain, mercurial and ambitions’ and prone to drinking in excess. He was however also ‘a brave and courageous, if untrained, officer whose military services to his adopted country proved to be an important watershed in Irish-American history’.

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

John M. Hearne and Rory T. Cornish (Eds), Thomas Francis Meagher; the Making of an Irish American (Dublin, 2006).

E,P, Cunningham, Thomas Francis Meagher - Dictionary of Irish Biography entry.

Daniel M. Callaghan, Thomas Francis Meagher and the Irish Brigade in the Civil War (2006).