Meagher of the Sword (1/3): Thomas Francis Meagher (1823–67) and the Young Ireland Rebellion, July 1848.

Ever since working in Dublin city, my bus carried me down the south-side quays and past the statue of Daniel O’Connell towards the Customs House. As you pass Eden Quay there is a pub that caught my attention with its name, Meaghers - I don’t know why, but it struck me as incredibly familiar for no particular reason at all.

I know very little of American history and particularly of the American Civil War in the 1860s. But some compartment in the recess of my mind dinged when I read the name of this pub - ‘there was an Irish general called Meagher in the Civil War wasn’t there?’. Similarly, I knew to some degree that the name held some importance in Ireland too.

I immediately bounded into searching after this figure and without delay my suspicions were confirmed - Thomas Francis Meagher was not only a general in the American Civil War, but was also central to the Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848 and the first flying of the Irish tricolour flag.

When I began reading, I quickly found that his story was too great to fit into a single post, so this will be a three-parter. Today I’ll be looking at his life up to the Young Ireland Rebellion of 1848 and the aftermath. Part 2 will deal with his later life and his influential involvement with the Irish Brigade in the Union Army during the American Civil War. And finally, Part 3 will look at his life after the events of the civil war, and his governorship of the Montana Territory.

***This is a bit of a long one - if you usually read my posts in the email only, it may cut off toward the end, but there should be a link at the top right hand corner of the email that will bring you to my web page for the rest.

Thomas Francis Meagher came from a privileged upbringing - of a middle-class catholic family, his father Thomas Meagher Jr. had made a name for himself in the ship-owning trade with Newfoundland. That he was privileged - Meagher was well aware as John M. Hearne points out – this self-awareness, it can be argued, instilled him with a sense of honour and of needing to earn a reputation as sincere and well meaning. His father fell in with O’Connell’s Repeal Association and Meagher in turn was nominated to Kings Inns as a law student by O’Connell in 1844.

Within a year he had dropped out to become more involved with the Repeal Association, Meagher began the first stop on a long road to revolution in Ireland. He was a member of that new generation entering into the political sphere - a branch of the O’Connellite grouping, Young Ireland.

As the 1840s progressed, tensions between the Repeal Association and Young Ireland group were stoked repeatedly over ways in which to appeal to Westminster and how to best go about campaigning for Repeal of the Act of Union. Matters came to a head decisively in 1846 in a speech given by Meagher in which he defended the right of an oppressed peoples to rely on violence as a course of action.

O’Connell had become alarmed at the level of militancy present in the Young Ireland group and brought forward the ‘peace resolutions’, whereby every member of the Association had to pledge to never take up arms to achieve their ends. It was at a full Association meeting on 13 July 1846 that O’Connell insisted ‘that the abstract principle of disclaiming physical force in any event must be held by every member of the Association’. The intention? To draw a hard line between the Old and Young Ireland - some historians concur with Meagher in his assessment that the O’Connell’s had conjured up a deliberate and premeditated plan to facilitate the expulsion of the Young Ireland faction.

Meagher resolutely abhorred the idea of the ‘peace resolutions’ - not out of any desire for blood lust and armed rebellion, but as a matter of free speech and principal. Meagher agreed that repeal should be only achieved by moral and peaceful means but held, that if it was not possible:

‘I am prepared to adopt another policy - a policy no less honourable though it may be more perilous - a policy which I cannot disclaim as inefficient or immoral, for great names have adopted its adoption, and noble events have attested its efficiency’.

In his remarks, Meagher invokes the memory of 1798 and the figures of both Wolfe Tone and Emmet. This was the first of three instalments of his speech which earned him the moniker, Meagher of the Sword - continually interrupted by O’Connell and his supporters it would not be fully complete until December of 1846.

In expressing his right to free expression at the next instalment on 27 July at a meeting where John O’Connell insisted that his father’s ‘peace resolutions’ had to be accepted by Young Irelanders if they were to remain within the Association. Meagher says;

‘In the exercise of that right I have differed, sometimes, from the leader of this Association, and would do so again. That right I will not abandon…I am not ungrateful to the man [O’Connell] who struck the fetters from my arms, whilst I was yet a child…but the same god who gave to that great man the power to strike down an odious ascendancy in this country, and enabled him to institute, in this land, the glorious law of religious equality - the same god gave to me a mind that is my own.’

What can be seen through much of what Meagher says is not the words of a fanatic but of a patriotic revolutionary whose sole purpose is to achieve what is best for his country. He does not advocate for outright violence – but simply argues that if a peoples voice is stifled, and constitutional methods barred, they should be permitted to rely upon armed resistance as the only form of meaningful resistance.

It is at this session that Meagher delivered the thrust of his sword speech;

‘Abhor the sword? Stigmatise the sword? No…for at its blow it cut to pieces the banner of the Bavarian, and through those cragged passes of the Tyrol cut a path to fame for the peasant insurrectionist of Innsbruck. Abhor the sword? Stigmatise the sword? No…for at its blow, and in the quivering of its crimson light a giant nation sprang up from the waters of the Atlantic, and by its redeeming magic the fettered colony became a daring free republic. Abhor the sword? Stigmatise the sword? No…for it swept the Dutch marauders out of the fine old towns of Belgium - swept them back to their phlegmatic swamps, sluggish waters of the Schelt…I learned that it was the right of a nation to govern itself - not in this hall - but upon the ramparts of Antwerp’.

Here he was again cut off by O’Connell - insisting that views were being expressed, entirely in opposition to the principles of the Repeal Association. After repeated attempts to continue the expression of his own opinions and beliefs, Meagher and a collection of others - William Smith O’Brien, John Mitchel and Charles Gavan Duffy - walked out of the hall. In the words of Hearne, here is where the Rubicon was crossed. Young Ireland seceded from the Association and placed them on a path to further fragmentation and radicalization.

Meagher finally finished his Sword Speech in December of 1846 - he attacked O’Connell for their concerted effort to purposefully denounce the Young Irelanders and force them into a corner. The inevitable result was the secession of the group from the Association for ‘had we assented to the peace resolutions, others would have been introduced to which we could not with common sense have subscribed’.

After the success of this final instalment, O’Connell attempted to mend relations to little avail. Even going so far as to personally invite Meagher back into the fold - the damage had been done. In January of 1847 the Irish Confederation was established by those who left the Association - it was to serve as an opponent to contest the Repeal Association in elections but it differed very little in its politics. They were virtually identical minus the peace resolutions.

It was to serve as a very weak an ineffectual opposition and by December 1847 it had still not developed a coherent and meaningful policy on how best to achieve repeal. Similar arguments which caused the rupture of 1846 began to surface even in the Confederation now, after the introduction of the Crime Prevention Bill in the same month. John Mitchel, one of the more militant members of the Confederation argued that certain provisions of the bill were ‘a direct invasion of the common rights and prerogatives of manhood…every man has the right to bear arms’. On top of this he began advocating for the formation of a militia for mutual defence - something which alarmed leading members of the group. A division formed between those still determined to follow a constitutional model and those more militant in their attitudes.

Meagher lamented;

‘My heart sinks under a weight of bitter thoughts, and I am almost driven to the conclusion that it would be better to risk all - to make one desperate effort - and fix at once the fate of Ireland…but an unconstitutional mode of action would not in the present circumstance succeed’.

It is clear at this point, from his sentiments and other writings around this exactly what form of independence Meagher sought. It was an independence within the framework of empire - a return to the status quo of the 1782 parliament under Grattan. He feared the notion of a fully democratized revolution - believing that himself and his compatriots would likely have been exterminated on ‘a Jacobin scaffold’. In this vein he claimed that ‘we propose to exhaust all resources of constitutional action, before we resort to other efforts for redress’.

Meagher was arrested in April 1848 on counts of sedition for suggesting that;

‘if the throne stand as a barrier between the people and their supreme right - then loyalty will be a crime and obedience to the executive, will be treason to the country…it will then be our duty to fight…if the constitution opens to us no path to freedom…then up with the barricades and invoke the God of Battles’.

In the eyes of the government - those were fighting words. He was fortunate to receive bail and immediately sailed for France as part of a delegation to congratulate the Second French Republic on their recent revolution - one of many to grip Europe in 1848.

They had hoped to receive support for the same cause back in Ireland but were met with very reluctant overtures of support - in reality the British had headed them off and came to an understanding with the new French government before the Confederation members had even arrived. Lamartine, the new French Foreign minister did not want to antagonise the British and jeopardize France’s independence. Upon their return to Dublin a reception was held in their honour on 13 April - it was at this meeting that Meagher presented an Irish tricolour flag of green, white and orange, when he said; ‘I present…to my native land and I trust that the old country will not refuse this symbol of a new life from one of her youngest children’.

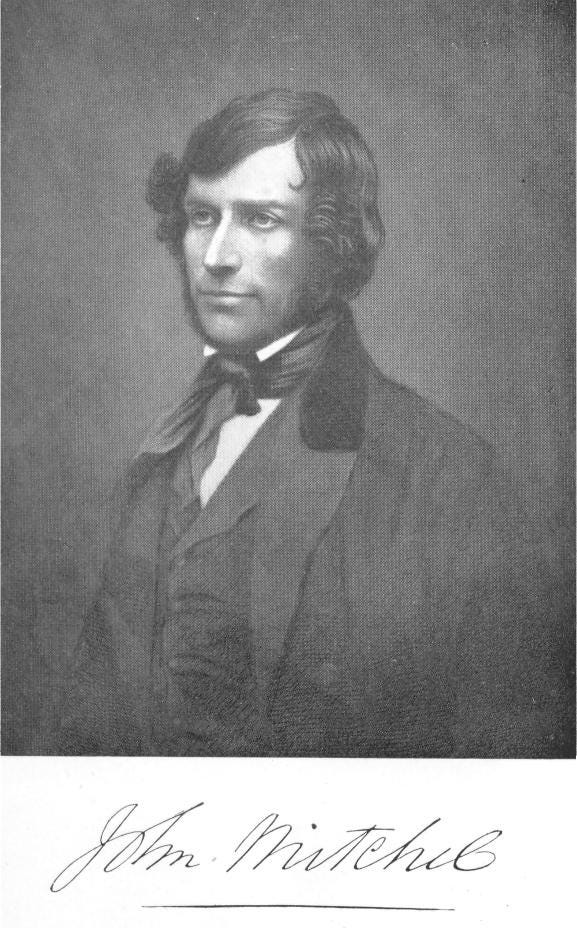

John Mitchel continued to stoke tensions throughout 1848 and dramatically widened the rift between himself and other Confederate leaders. While most still hoped for a domestic legislature within the imperial framework - Mitchell advocated for an independent republic. What was on the minds of all however were the trials of those arrest in April - Meagher, O’Brien and Mitchell. Meagher and O’Brien were accused of sedition but never charged in the end. By the time Mitchel’s trial arrived though, the Treason Felony Act was passed making it easier to charge those involved as instigators of disaffection, particularly in the press. This made for an easy conviction against Mitchell who was sentenced to fourteen years transportation.

While Mitchel was a thorn in the side of both the government and the Confederation - the remaining members were alarmed, realising that at any moment they could be picked up for past offences under the new law. They were forced to abandon any overt displays of militarism. Feeling themselves being arbitrarily shut out of political agitation, a decision was made then, to form a smaller council of 21 members to develop a coherent plan of action - to affect a blueprint for revolt in the near future. Meagher assumed leadership of this council and proclaimed; ‘We shall be martyrs or the rulers of a revolution’, putting the Confederation well and truly on the path to war.

A rebellion was expected in government circles but not until the autumn, after the harvest had completed - but Confederate popularity had rose dramatically in the months of May and June and officials were being urged to take action now. Between 8-11 July leading members of the Confederation were arrested - Meagher down in Waterford. Supporters had rallied to his house to prevent the arrest but he urged them not to take any actions that may be deemed unconstitutional. As before, he was out on bail days later and returned to work, stoking the masses at a monster meeting at the summit of Slievenamon.

The ultimate shock to the Confederation leadership came on 22 July when the government suspended Habeas Corpus. In the words of Meagher; ‘death itself could not have struck me more suddenly than this news. I had fully calculated…that nothing would occur for three or four weeks at least, to precipitate a rising’. This decision rather than dissuade the insurrectionists, convinced them to act now rather than later.

The rebellion broke out but it was nothing but a minor conflict over a farmhouse at Farranrory near the town of Ballingarry on 29 July 1848 and a number of subsequent skirmishes. The whole affair essentially lacked organisation and a coherent military strategy once it moved on to Carrick-on-Suir. Attempts were made elsewhere at Portlaw, Glenbower and Kilmacow in Kilkenny - but all resulted in failure which convinced the rebels to abandon their assault. After no more than a week the rising was over.

Meagher was not present at the conflict but was arrested near Cashel and charged with high treason. In October 1848, he was sentenced to death but had this sentence commuted in exchange for transportation to Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania) in 1849. It must be noted that Young Irelanders were given rather preferential treatment on both the voyage and during their time in Van Diemen’s Land. During his time there, Meagher was allowed to meet with other Young Irelanders, acquire a sailing boat for personal use and found love in 1851 with Catherine Bennett. All the while, plans were in motion for his escape to America by other Irish exiles living in New York.

The failure of the rebellion came down to three things - the government action in April 1848 (Treason Felony Act) prompted more immediate action than the Confederation were expecting, the refusal of the Catholic Church to support such an uprising - many of the local Confederate Clubs were headed by influential priests who discourage other members from taking up arms on the day of revolt; and the news of atrocities in revolutionary Paris where thousands were reported to have been killed. The combination of these events ensured that any attempt at insurrection would have been unsuccessful.

Meagher himself later recounted;

‘I entertained no hope of success. I knew well the people were unprepared for a struggle; but at the same time, I felt convinced that the leading men of the Confederation were bound to go out, and offer the country the sword and banner of revolt, whatever the consequences might result to themselves from doing so’.

This has been but a part of Meagher’s story - he continues to impact the world in many significant ways, some of which I will look at in detail next time.

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

John M. Hearne and Rory T. Cornish (Eds), Thomas Francis Meagher; the Making of an Irish American (Dublin, 2006).

E,P, Cunningham, Thomas Francis Meagher - Dictionary of Irish Biography entry.

Arthur Griffith (ed.), Meagher of the Sword: speeches on Ireland 1846–1848 (1916).