If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

In modern times, the name of George Washington is one of unassailable distinction. His name adorns buildings, towns, and states across the United States of America. He is remembered as the first Commander-in-Chief of the American military and the first President of the United States. He set a precedent in politics of the age in setting clear boundaries on the limits of the executive office, setting a trend to be followed by near every president after him. After serving two terms as president, he relinquished power to the next successful candidate in an election.

This is how many remember him, and posterity has done the personality of Washington well. If we go back to those fateful years of the American War of Independence however - we can see that people had much less faith in the ability of Washington. In the first few years after hostilities broke out, c. 1776-79 - two commanders took the lead in the American military. One was recognised for his persistent failures and retreats, the other was looked upon generously for his victory over the British army.

Horatio Gates was commanding the American troops on the fields of Saratoga, New York when he inflicted a crushing defeat against the British troops. After the Battle of Saratoga the personality of Horatio Gates was ascendant. His victories superseded those of Washington and left many wondering if Gates should really be Commander-in-Chief. Washington’s performance in comparison was lacklustre - he had sustained repeated defeats forcing retreats at every turn at New York, Brandywine Creek and Germantown.

The division of support for both Washington and Gates was embodied by both the military hierarchy and Congress itself - the most prominent of Washington’s detractors were Samuel Adams, Thomas Mifflin, and Richard Henry Lee. While Adams and Lee were openly sympathetic to Gates, they primarily argued that Congress should have a greater supervisory role over military affairs, not wishing Washington to accrue too much power and influence. Adams in relation to matters under the control of Washington is quoted:

‘Oh, Heaven! grant us one great soul!…One active, masterly capacity would bring order out of this confusion and save this country’.

Another such supporter of Horatio Gates was a Thomas Conway. Conway was born in Kerry to a Catholic family in 1733. At the age of 14 he went to France where he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the infantry of Clare's regiment in 1747. He served in this unit until 1775 when it was subsequently amalgamated into another. In this time he rose through the ranks, eventually becoming a Colonel in 1772.

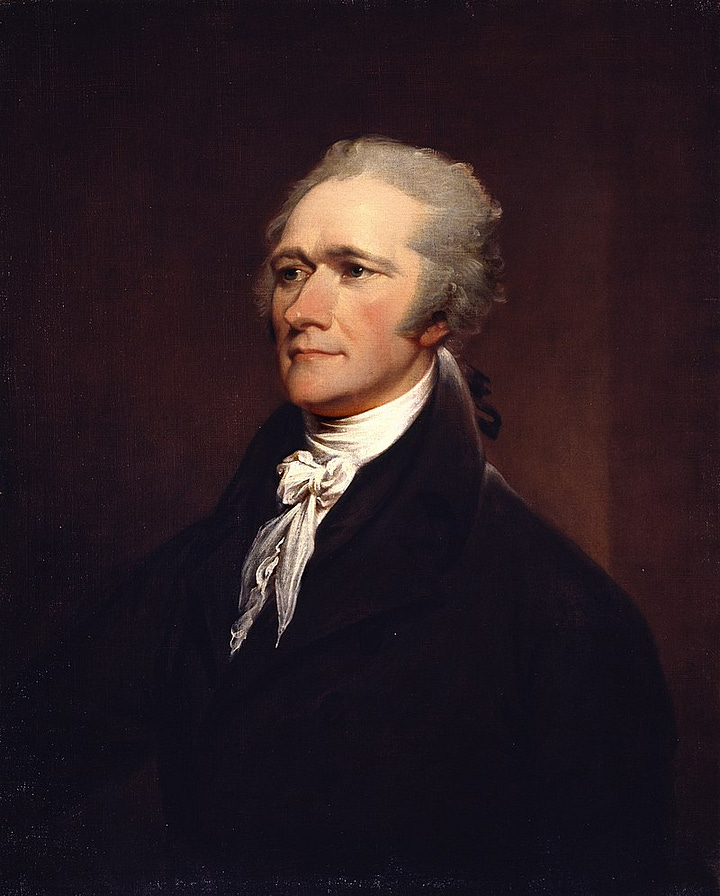

Conway requested to go to America when France joined hostilities on the side of the revolutionaries. He was appointed Brigadier-General by Congress in 1777 and commanded troops under Washington at both Brandywine and Germantown. He was deemed an arrogant officer and hostile to the leadership of Washington. Both the Marquis de Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton, close confidants of Washington had misgivings about Conway’s character. Lafayette thought him ‘ambitious and dangerous’ and Hamilton said: ‘There does not exist a more villainous culminator or incendiary’.

Conway embedded himself in the struggle between Gates and Washington in 1777-8 when there was a loosely organised attempt to remove Washington from command and replace him with Gates. Conway was considered the supposed leader of this movement - and it is from him that the name of the scheme, The Conway Cabal, is drawn. In reality this conspiracy was no more than Conway openly airing his misgivings about Washington’s command, and attempts by members of Congress to curb Washington’s power - but at a time of war and crisis for the revolutionaries, it was borderline treasonous.

Having served under Washington at both Brandywine and Germantown, Conway arrogantly denounced Washington’s ability as a leader, while boasting of his own exploits. In October 1777, Conway wrote to Gates after the Battle of Saratoga claiming:

‘Heaven has been determined to save your country or a weak general and bad counsellors would have ruined it’.

He was also, around this time to have been overheard saying ‘as to his (Washington's) talents for the command of an Army, they were miserable indeed’ - in relation to his leadership abilities at Brandywine specifically.

Such treasonous talk was not discouraged by Gates and was let go by unaddressed. It is only when word of such a letter reached Washington that we see Gates attempt to deflect. Washington had, by chance it seems, to have stumbled upon the information after an aide of Gates, James Wilkinson became drunk and told the details of the letter to a Major McWilliams, working under Lord Stirling. Stirling was aghast at such open disdain for their commander in chief, ‘such wicked duplicity of conduct’ and felt obligated to report the letter's contents to Washington. At the same time, Gates had attempted to place the blame upon Washington’s own aide-de-camp, Alexander Hamilton for leaking details of a confidential letter. Gates ultimately withdrew his accusations when evidence was provided that it was in fact Wilkinson, a man who was ‘a flamboyant character with an incurable weakness for liquor’ who had leaked the information.

Ron Chernow highlights that little exists to definitively call this episode of American history an open conspiracy to replace Washington. There is clear proof that Congress and Washington’s detractors sought to severely weaken the Commander-in-Chiefs powers, but nothing more. This was grown out of a fear that the public were deifying the general to a level similar only to a king. Around this time a paper was being circulated anonymously by Washington’s enemies called ‘Thoughts of a Freeman’, in which it was critical of Washington's generalship, and particularly critical of the apotheosizing cult that had grown around him: ‘The people of America have been guilty of making a man their God’.

In November 1777, Congress moved to curb Washington’s power significantly. Conway after being found out, attempted to resign his post citing disagreements with Washington and another officer, Johann de Kalb being promoted instead of himself. Congress refused to accept the resignation and instead promoted him to Inspector-General in Washington’s army - where he would report to the Board of War, not Washington. Similarly Horatio Gates was made President of the Board which came to serve as an oversight committee of military affairs - a way to keep tabs on Washington’s influence.

Countervailing forces had simultaneously already begun to reign in the Conway conspirators. In January 1778 Henry Laurens, now President of Congress stated:

‘I will attend to all their movements and have set my face against every wicked attempt, however specious’.

Washington’s popularity was simply unassailable even in the face of such strong criticism in Congress. The so-called Cabal collapsed on 19 January 1778 when Gates and Conway refused to hand over the ‘weak general’ letter to Congress. At the same time, many generals serving under the command of Washington sent in letters of unhindered support to their Commander-in-Chief. Congress happily accepted Conway’s letter of resignation the second time around.

Conway remained a thorn in the side of Washington, bad-mouthing him to just about anybody who would listen. Affairs had escalated to the point where if he would not shut his mouth, somebody else would - and in fact they did, quite literally. On 4 July 1778, John Cadwalader, a pro-Washington militia leader from Pennsylvania grievously wounded Conway in the mouth in a duel. Thinking himself dying after the fact, Conway wrote a letter of apology to George Washington, for all the wrongs he had done him.

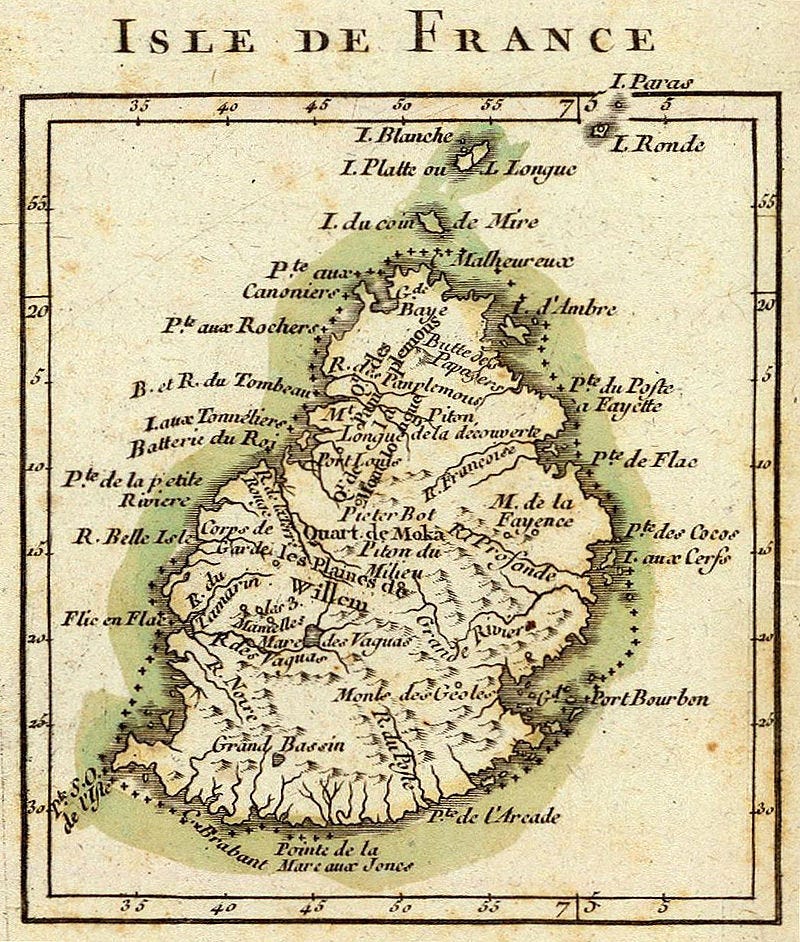

Conway would return to the French army after his brief tenure in America. Leaving the Cabal episode behind him he would reach the peak of his ambition in French service. Appointed Governor-General of all of the French settlements east of the Cape of Good Hope in April 1789. He proved unpopular in his post as Governor on the Isle de France, modern day Mauritius and when news of the French Revolution reached it, riots broke out and many denounced Conway as a tyrant. Only reluctantly did he agree to the creation of a colonial assembly, which he was soon plotting to overthrow.

After colonial reforms were introduced from Paris, he was forced to resign in embarrassment and return to France where he fought for the Royalist armies in southern France. By 1794, under threat of arrest and possibly execution, Conway fled to England where he lived in exile. He and his brother, who also served with distinction in the French military were given commands from Prime Minister William Pitt to command Irish Brigades. It is unlikely that much progress was made in this regard however as Conway died not long after, in 1795 at the age of 62.

We can only ponder as to Conway’s motivations in both the 1770s fighting for America and the 1790s siding with Royalists. Was his support for America simply a pragmatic choice to harm France’s enemy and to garner glory for himself? Did he disapprove of the French Revolution because his ambition soared too high and he made enemies? The question of idealism versus pragmatism is certainly one which can be applied to many revolutionaries of the time and it is a question I intend to ask of more individuals moving forward.

Further Reading:

Stephen McGarry, Irish brigades abroad: from the Wild Geese to the Napoleonic Wars (The History Press, 2014)

Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (Penguin Books, 2004)

C.J. Woods, ‘Thomas Conway’ in Dictionary of Irish Biography, online at: https://www.dib.ie/biography/conway-thomas-a1988

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or encourage me to do more, you can buy me a coffee! nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor