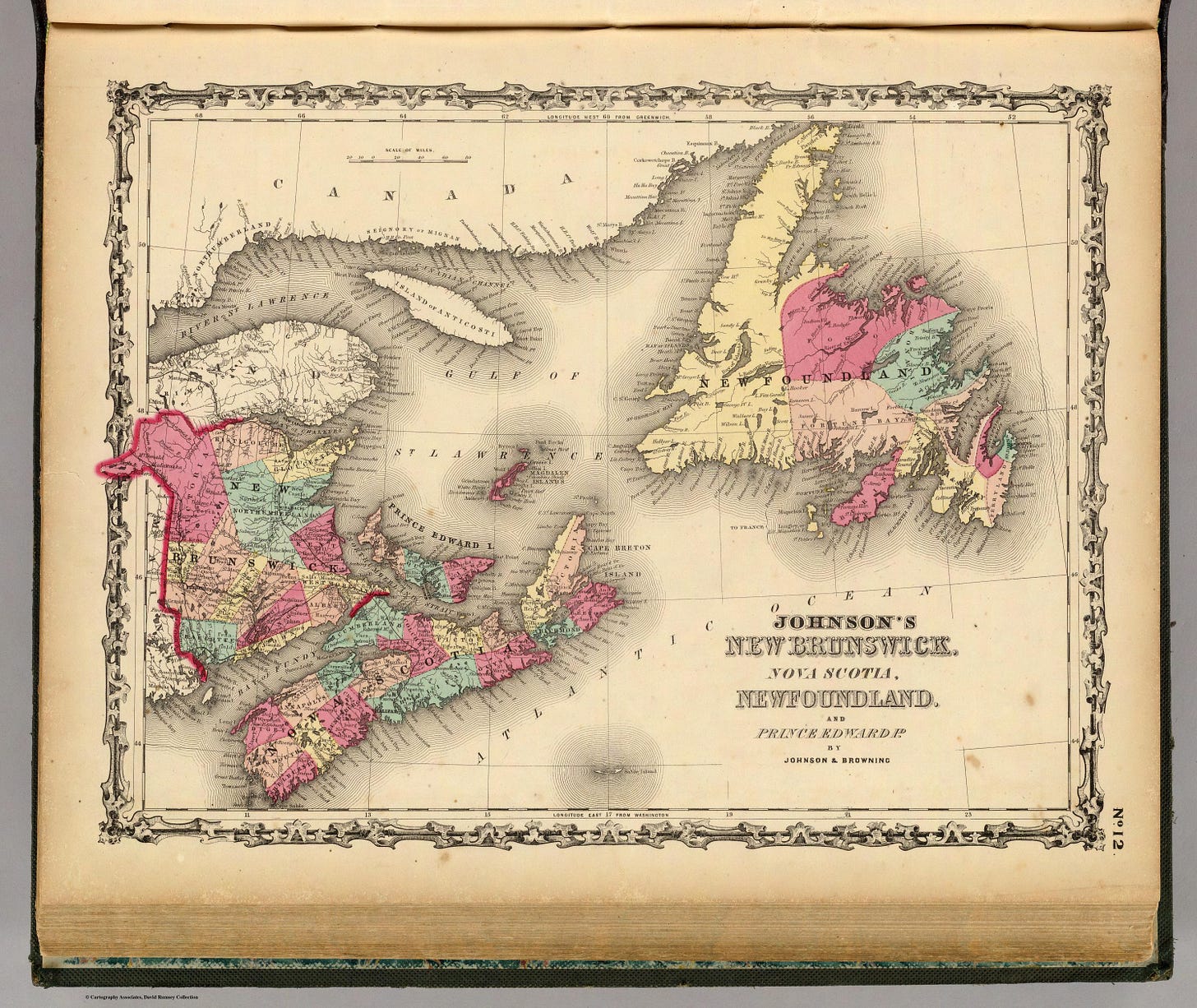

The migration of Irish settlers to Atlantic Canada is a story of persistence, enterprise, and transformation—one that spans from the windswept shores of Ireland’s southern ports to the dense forests and thriving harbours of Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island. In her meticulous and compelling work Atlantic Canada's Irish Immigrants: A Fish and Timber Story, Lucille H. Campey reclaims this narrative from over-simplifications that have traditionally linked Irish emigration solely to the catastrophe of the Great Famine. Instead, she presents a deeper and more nuanced account, one shaped as much by opportunity as by hardship

While hardship—economic insecurity, landlessness, and socio-political marginalization—formed a backdrop for many Irish departures, Campey illustrates how Atlantic Canada offered early and distinct pull factors. Among these were the cod fisheries of Newfoundland, later the vast timber resources of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and an increasingly global trade network that linked Irish merchant houses to colonial outposts across the Atlantic. These Irish migrants, far from being victims in a one-way journey of despair, were often active participants in a web of transatlantic commerce, forging new communities and reshaping local economies in ways that are still felt today.

Early Migration and the Fishing Industry

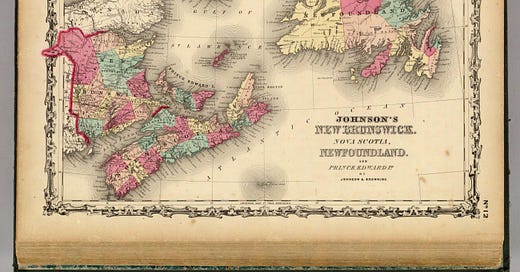

The origins of Irish settlement in Atlantic Canada can be traced back to the 17th century, when a commercial relationship emerged between southeast Irish ports—especially Waterford, Cork, and New Ross—and the Newfoundland fishery. These trade ties laid the foundation for the first waves of migration.

Initially, Ireland’s involvement in the fishery was indirect: Irish merchants supplied butter, pork, linen, and salt beef to English fishing crews operating off Newfoundland. However, by the early 18th century, increasing numbers of Irish labourers were recruited directly to serve aboard fishing vessels or to work ashore salting and drying cod. These workers, predominantly Catholic and hailing from agrarian backgrounds in Munster and Leinster, became seasonal migrants, spending summers fishing and winters back in Ireland.

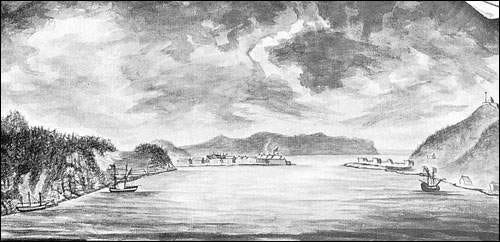

Over time, this temporary pattern gave way to permanent settlement. By the 1760s and 1770s, Irish families were establishing roots along the Avalon Peninsula and other fishing hubs in Newfoundland. Towns such as St. John's, Ferryland, and Harbour Grace began to develop Irish-majority populations. The establishment of Catholic missions, informal schools, and vernacular Irish customs reinforced the idea of a transplanted culture rather than simple transplantation of labour.

Lucille Campey documents the personal experiences of early settlers with a humanizing lens. One illustrative figure is John Francis O'Leary, who arrived in the 1830s to work in the fishery. His contract, which included “half the fish he catches, rations, and cuffs (fingerless mittens) in the winter,” reveals not only the tough conditions but also the self-sufficiency and mutual dependencies embedded in the fishery economy.

Crucially, Campey argues that this migration was not solely driven by desperation. It was also about aspiration. The cod fisheries provided reliable work, and while the life was arduous, the opportunities for advancement were real. Some Irish migrants rose through the ranks to become ship captains or independent fish merchants, creating footholds for later generations.

The Timber Boom and Irish Labour

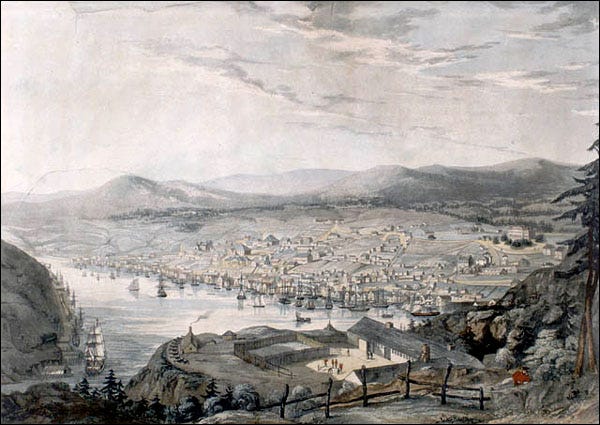

By the early 19th century, as the British Empire’s demand for timber surged in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars and the expansion of industrial cities, Atlantic Canada’s economic centre began shifting inland. New Brunswick, with its vast forests and accessible river systems, became the epicentre of the timber trade. It was here that the Irish found their second great opportunity in the New World.

The timing of this boom coincided with worsening socio-economic conditions in Ireland, especially for small tenant farmers. However, unlike the famine-era migrations to come, many Irish in the timber years of the 1810s–1830s arrived with some resources, family networks, or employment guarantees. Campey’s research dispels the image of destitute migrants flooding the region:

“They were not pitiful refugees, but people who saw in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia a place where they could own land, build communities, and prosper.”

The timber economy required enormous seasonal manpower. Irish men took jobs as lumberjacks, log drivers, and mill workers during the winter months and often farmed during the summer. This dual economy allowed them to accumulate savings, acquire land through Crown grants or purchase, and invest in their families' futures. Irish names appear frequently in early land grants in the Miramichi Valley, the Saint John River watershed, and along Nova Scotia’s Eastern Shore.

Many of these settlers, notably from Cork and Kerry, formed tightly-knit Catholic communities. In New Brunswick, Irish settlers founded what became known as the “Teetotal Settlement” near Stanley, a model farming community guided by sobriety and cooperation. The community rejected alcohol and strove for moral improvement and self-reliance—a stark contrast to the popular stereotypes of Irish drunkenness that plagued urban centres.

Irish women were integral to these timber communities as well. As domestic workers, farmers, midwives, and teachers, they contributed to the social and moral structure of rural settlements. Campey underscores how Irish families—not just individual men—were critical agents of colonization in these rural frontiers.

Mercantile Networks Linking Ireland and Atlantic Canada

Migration was never a one-way journey. At the heart of Irish settlement in Atlantic Canada was a vibrant transatlantic mercantile system that linked Irish ports with colonial markets. This triangle of exchange—fish, timber, and people—allowed the Irish diaspora to maintain commercial, familial, and cultural connections with their homeland.

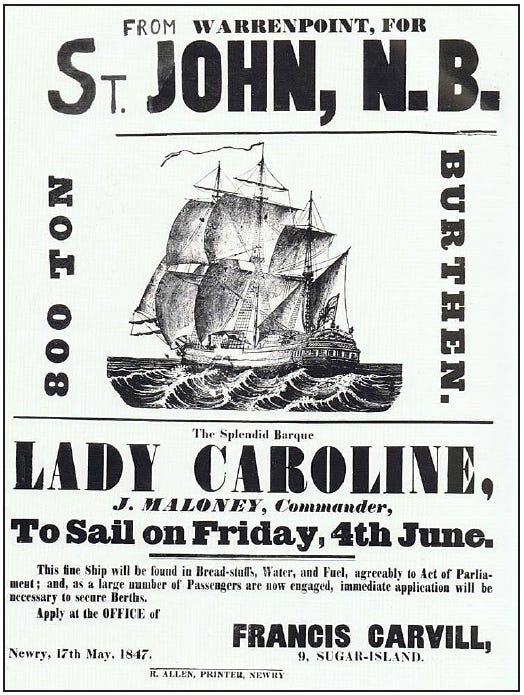

Irish merchant families, such as the Carvills of Newry, were key players in this system. Francis Carvill was a shipowner, timber broker, and emigration agent who leveraged his business empire to transport both goods and people. His ships, like the Mary Anne and the British Queen, were copper-fastened vessels capable of carrying lumber to Ireland and emigrants to Saint John, Halifax, or St. John’s.

These voyages were part of a broader trade pattern: timber and cod traveled eastward, while manufactured goods, salt, and migrants traveled westward. Onboard ships, emigrants were both passengers and cargo—often working in return for reduced fares. Campey notes that some Irish agents were genuinely invested in the welfare of their passengers, arranging food and lodging, while others exploited the desperate.

Irish ports such as Waterford, Cork, and Limerick thrived on this commerce. They became hubs of shipping, provisioning, and recruitment. In fact, the timber trade with New Brunswick had such economic significance that entire industries in Irish port towns became dependent on colonial demand.

Irish merchants in Atlantic Canada built upon these links. Many transitioned from retailing Irish goods to establishing their own shipping firms and export companies. They forged bonds with Anglican and Presbyterian business partners, forming a kind of “Irish Atlantic elite” that blurred sectarian divisions in pursuit of commerce.

These connections also facilitated cultural continuity. Irish-language newspapers circulated among diaspora communities, Catholic priests moved between Newfoundland and Munster, and letters—filled with news of births, marriages, land acquisitions—flowed back and forth. This network ensured that Irish migrants were not isolated, but rather engaged in a transatlantic dialogue of ambition and adaptation.

Irish Social and Political Integration

While economic integration came relatively swiftly, social acceptance took longer. Irish Catholics, in particular, faced prejudice and marginalization, often being portrayed in local newspapers as disorderly, unskilled, or politically subversive. Yet Campey shows how Irish communities pushed back against these tropes—through education, religious organization, political engagement, and press advocacy.

In Saint John, New Brunswick, the Freeman, a Catholic newspaper launched in the 1840s, offered a platform to articulate Irish perspectives and challenge sectarian bias. Irish mutual aid societies, including St. Patrick’s Societies and Friendly Sons of Erin, emerged to assist newcomers, advocate for civil rights, and celebrate heritage. These organizations helped pave the way for Irish participation in municipal and provincial politics.

By the late 19th century, Irish Canadians had moved from the economic margins to positions of influence. Campey recounts the careers of Irish-born doctors, lawyers, and legislators who contributed to shaping the governance and identity of Atlantic Canada. In Halifax, the Irish were involved in business, education, and shipping. In St. John’s, Irish influence helped define political allegiances and municipal development.

The Irish Legacy in Atlantic Canada

The story of the Irish in Atlantic Canada is not merely one of survival—it is one of shaping. From the cod fishers of Newfoundland to the timber workers of New Brunswick, and from merchant adventurers in Newry to community leaders in Saint John, the Irish contributed materially, socially, and spiritually to the building of a new world across the sea.

Campey's Atlantic Canada's Irish Immigrants reminds us that history is rarely one-dimensional. While famine and hardship undeniably played roles, they do not define the totality of the Irish experience in Canada. Just as importantly, it was ambition, family strategy, commercial opportunity, and cultural resilience that brought thousands across the Atlantic—and saw them flourish on new soil.

Today, the Irish legacy in Atlantic Canada lives on in its place names, churches, customs, and communities. The roads built, the timber milled, the fish cured, and the families raised are all testaments to a people who came not just to escape, but to build.

Help Ireland and the Age of Revolution grow!

This newsletter is and always will be free to access, enjoy and engage with, but it does take time and effort to create alongside my usual work routine. If you enjoy what I do here and want to see it become even better, please do consider chipping in!

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

Lucille H. Campey, Atlantic Canada's Irish Immigrants: A Fish and Timber Story (2016).

John Mannion, Irish Settlements in Eastern Canada: A Study of Cultural Transfer and Adaptation (1974) - Especially Volume 2 (The Irish in the New Communities) and Volume 4 (The Meaning of the Famine) offer relevant chapters on early Irish settlers in North America, including eastern Canada.

Nicholas Canny and Mary MacCarthy (eds.), The Irish in the Atlantic World (2004).

Patrick O’Sullivan (ed.), The Irish World Wide: History, Heritage, Identity (6 vols., 1992–1997).

Great article thanks Ruairi.

Great articles. Well researched, and well paced. Thanks.