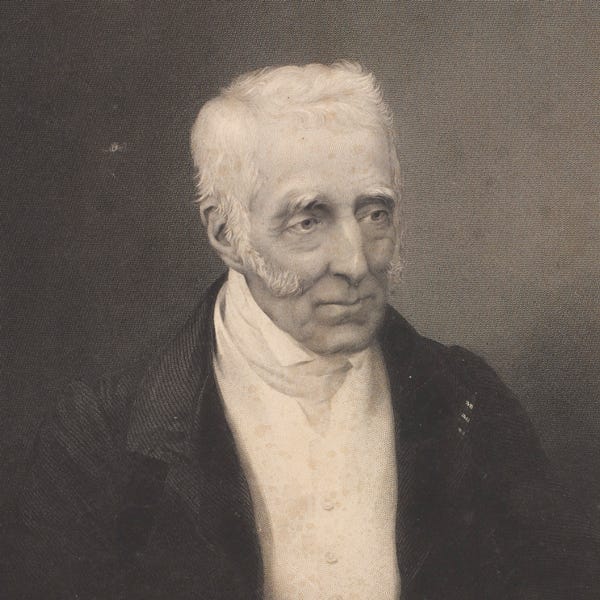

There is a towering figure of Irish history which embodies the period which forms the focus of this blog. Much like Benjamin Bloomfield, his life spans the breadth of this period – being born in a dramatically different world than the one he died in. He is also a divisive figure in an Irish context, in that his ‘Irishness’, for lack of a better word, has been disputed over the years and has been since the era of Catholic Emancipation. He is undoubtedly a figure some would be unaware of being Irish, I certainly have no memory of him being taught to us in school at any level. Yet for people in Ireland and more specifically Dublin and Meath – his presence is impossible to ignore.

Arthur Wellesley – originally Wesley, but changed later in his life by a brother to its original and more aristocratic, Wellesley. He was of an Old English family which could trace its lineage as far back as the Norman invasions of Ireland, later Tudor conquests and eventual settlement in the 16th Century. Therefore, when we come to Arthur’s day – it is difficult to fully remove him from Ireland, his connection to Ireland can be of little dispute despite what Daniel O’Connell later stated;

‘He was born in Ireland but is not of it. Being born in a stable does not make one a horse’.

This quote, is often misrepresented as being said by Wellesley himself – usually by those attempting to portray his disdain for being Irish, of which there appears to be little evidence. One will find articles arguing that he did or did not say a lot of things - more often than not the quotes in question have been cherry picked, poorly researched or misrepresented.

Some quotes have been used to reinforce a particular identity and image. For instance, he is quoted to have said that the Battle of Waterloo was won on the fields of Eton College, something which simply makes no sense. To qualify, for one, he would have had to have fond memories of his time there – in reality he despised his experience of Eton and was glad to have been removed early due to family financial troubles. Realistically, he would have believed the battle won on the fields of Ireland for he held the performance of the Enniskillen brigades, the Connaught Rangers and individual Irish soldiers in high regard following the Battle of Waterloo. For an example look to a recent blog of mine about Sergeant James Graham of the Coldstream Guards.

While the general trend since the Tudor settlements was for the Anglo-Irish to try and distance themselves from Irish and even Norman settlers, this dynamic of identification shifted in the eighteenth century. This is clear in the distinct rise of Irish nationalism under the Protestant Ascendancy. The origins of Irish Nationalism is often linked with the Rebellion of 1798 and the birth of Irish republicanism. In reality the formation of a nationalist ideology and the venture for greater national independence from Westminster was in the form of Protestant Nationalism in the ‘Patriots’ movement of Grattan’s Parliament. Therefore, we need to maintain a degree of hesitation when trying to identify what figures of the time themselves identified as.

Identity in late eighteenth century Ireland was much more fluid than is often presumed. Wellington identified with his Irish roots but like many of his class, also considered himself British. These were not mutually exclusive and it is not until after the 1790s that we see more distinct sectarian lines being drawn in the sand. This is not to say that those sectarian lines were in any way definitive either. After Union there continues to be rebellious Protestants and Catholic loyalists.

Attempts have been made in recent years to revive the image of the Duke of Wellington - the title given him in recognition of his commanding role during the Napoleonic Wars - as someone of Irish note, to be remembered as an Irish figure. One need not look far, depending on what part of Ireland you find yourself in. In Dublin, if one pays attention there are references to Wellington in multiple places, one of which is perhaps the most obvious and sizeable monument the city holds. The Wellington Testimonial in the Phoenix Park is resplendent and garish – reminiscent the Washington Monument in a way - though construction began long before the American counterpart - it is a large obelisk, the funding for which was crowdsourced. Along the Liffey in Dublin, one of the quays is adorned with his name and in Trim the Wellington Monument constructed there is reminiscent of Nelson’s pillar which used to stand on O’Connell Street. If one chooses to look, Wellington they will see.

If we look to his time as Chief Secretary of Ireland in 1807-8 – this post, by the nineteenth century had come to perform the role of the Lord Lieutenant, essentially. The way in which he managed the state of affairs serves to highlight his political nature which becomes clearer in his later life. He was a man determined to avoid the miasma of party politics and always did his best to stay above the fray of infighting. It is clear that the way he came to view Ireland after the Act of Union was not in the binary sectarian way others had become prone to. He viewed the people of Ireland, through a, perhaps more class based lens than religious. He enforced anti-Catholic laws with ‘mildness and good temper’ - and when parades were planned to celebrate the defeat of the 1798 rebels, Wellington had them banned to prevent further division in society. Similarly, he refused to grant office to fanatical Protestants for the very same reason.

Wellington had developed a distinct fear of radical political positions and those who stood over them along with a fear of popular public politics which promoted greater agency amongst the lower classes of society. Throughout his lifetime, he witnessed revolutions across the Atlantic world, rapid industrialisation and dramatic shift in urban/rural demographics. Through this time his opinions remained based upon 18th century principles, he carried over military practices of staunch discipline – but also carried over archaic opinions of class structure.

He believed gentlemen had a role to play and feared giving too much power to the lower classes. This is embodied by his refusal to introduce and support Parliamentary Reform later in his political career in the 1820s-30s. This is perhaps the greatest stain on his reputation – he was wedded to eighteenth century practices of class and social civility, refusing to move with the times and welcome change with open arms. He similarly rejected further Catholic Relief Acts – standing by the government throughout the 1790s, and still holding fast by the early 1820s, it was only when he felt forced to act, did anything change.

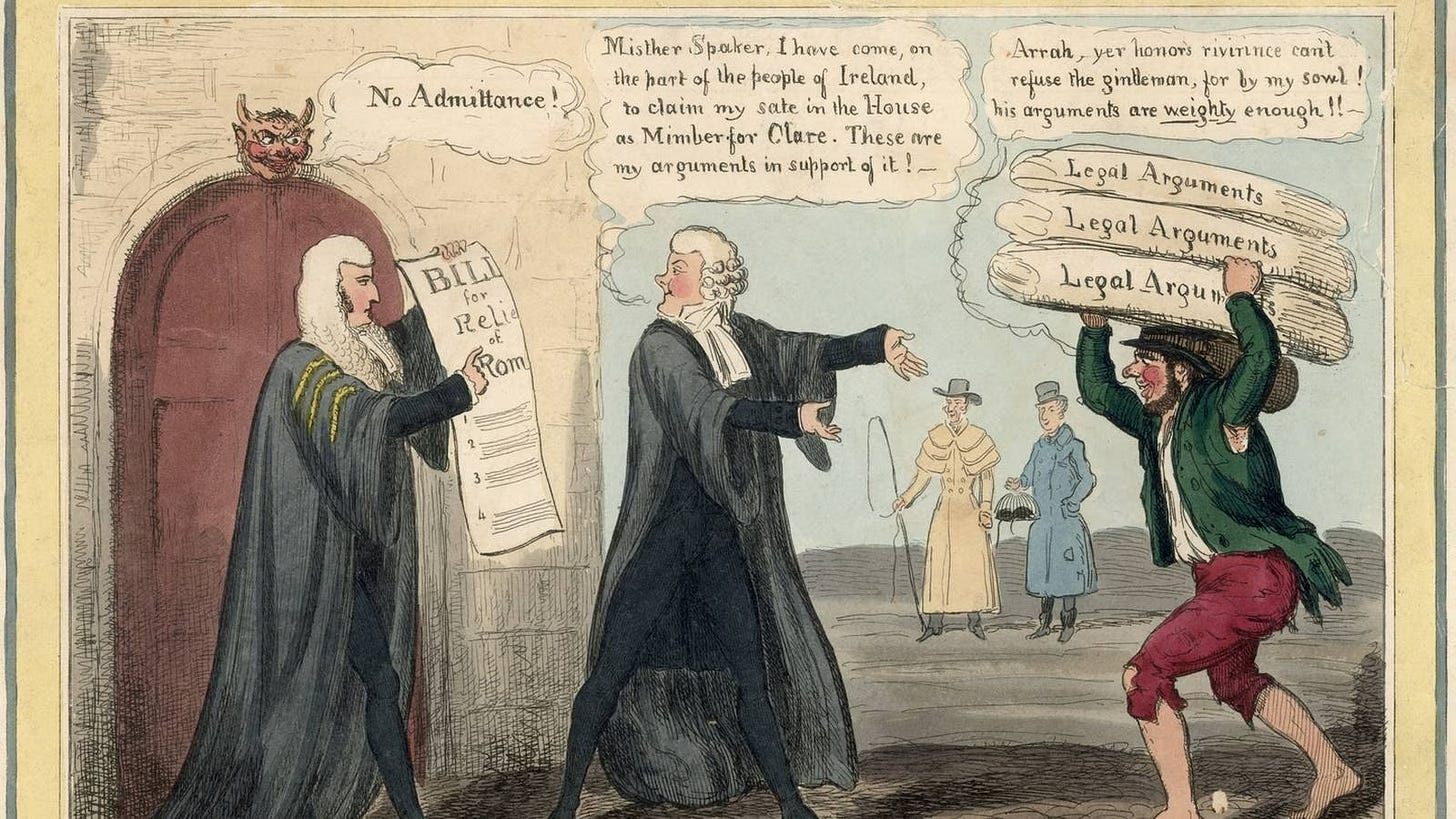

Like many moderates, on the issue of Catholic Emancipation, Wellington disagreed with its introduction for the most part – skirting along the side-lines and not willing to take a position on the matter. He is often applauded as the Prime Minister which introduced the legislation eventually in 1828. It is important however to dispute the reason he did so. It was not because of sudden patriotic desire to free the people of his country. It was rather forced upon him when Daniel O’Connell was elected to Westminster and the absurdity of existed Penal Laws became paramount. A catholic could run for election and receive votes, they could even win, but they could not take their seat in Westminster.

Concessions had been granted to Catholics on a graduated basis since the 1780s but too many feared the result of fully emancipating them and granting them access to the political system. Pre-1800 the fear was that the Irish parliament would devolve into anarchy and the Protestant Ascendancy would be cast out of the island – fears of a reversal of land confiscations in the 17th Century were at the forefront of many minds.

Post-1800 the fear of admitting so many Catholics to Westminster was the barrier, but this fear was unfounded. To take one’s seat in Westminster they had to swear an Oath of Supremacy, declaring the monarch of Britain to be the head of the church, not the Pope, forcing Catholics to renounce their faith.

It is for this reason that O’Connell’s election in a Clare by-election in 1827 posed a serious problem to the established order and Catholic Emancipation. It brought to the fore the issue of restricting the rights of Catholics. When O’Connell won his election, Wellington remarked;

‘This state of things cannot be allowed to continue … Something must be done’.

From this point on, he fought for the introduction of Catholic Emancipation in a very meaningful way. He had been warned before forming a government by George IV that the only issue not to be touched, was that of Catholic Emancipation. His fight to introduce the legislation is a testament to his refusal to delve into the depths of party politics. Frustrating hardliners on both sides, it required adept politicking to introduce it – and introduce it he did with a large majority of 116 votes. The size of the majority particularly annoyed George IV.

This is the close of Wellingtons involvement with Ireland in any meaningful way. He hadn’t set foot in his birth country since his tenure as Chief Secretary twenty years earlier and he would never set foot in it again. When his childhood estate was up for sale, the last parcel of land in Ireland connected to the Wellesley family – an effort was made by him to purchase it, but nothing beyond enquiries were made and the sale never complete. It had become clear during the debates for Emancipation that Wellington was far from reluctant about his heritage at this stage of his life.

In 1821, when invited to participate in an event for the Orange Order, Wellington refused explaining a year later;

‘I confess, that I do object to belong to a Society from which …. a large proportion of His Majesty’s subjects must be excluded, many of them, as loyal men as exist….’

This objection was only natural, he went on;

‘from one who was born in the country in which a large proportion of the people are Roman Catholics, and who has never found that, abstracted from other circumstances, the religious persuasion of individuals affected their feeling of loyalty.’

In this we can sense a degree of pride in where he was from, an affinity with his homeland and the people within it.

When introducing the second reading of the bill for Catholic Emancipation – many who opposed the measure argued that O’Connell and his Catholic Association should be snuffed out entirely. In response to such rhetoric Wellington responded, in what some have deemed possibly the best speech of his political career:

‘But my Lords, …I must say this, that if I could avoid, by any sacrifice whatever, even one month of civil war in the country to which I was attached (meaning Ireland), I would sacrifice my life in order to do it.’

Sophistry or not, Wellington made clear where he held Ireland within himself as a part of his own identity. He may have at times reduced his connection to it, but time and again he based the decisions of his political life upon what he deemed to be in the best interest of Ireland. He was, therefore, not the reluctant Irishman he is at times portrayed to be.

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

Richard Holmes, Wellington: The Iron Duke (London, 2002).

Lady Elizabeth Longford, Wellington: Proud to be Irish - a lecture to the Wellington Congress Trim (1992).

For Daniel O’Connell’s stable quote often attributed to Wellington - Shaw’s Authenticated Report of the Irish State Trials, 1844.

An especially excellent one, Ruairi.

Have you ever visited Apsley House?