One area of deep fascination in which I keep finding myself, and which I plan to continue sharing with you all is the stories of the Irish in the Spanish speaking world of the 18th and 19th centuries. The more I read and research certain figures the more I stumble across, and the more I unearth.

When I first encountered Alexander or Alejandro O’Reilly I marked a note beside it - “Spanish Louisiana”. Nothing more. Little did I expect when I began researching, not only to find out about his role in the Spanish takeover of the formerly French colony, but I discovered the architect behind the modernization of Spain’s 18th century army. A man whose influence extended all the way to the kings court, who served as governor of a Caribbean colony, Military Governor of Madrid, and Inspector General of Infantry for the entire Spanish army.

Rise through the Ranks

Alexander was born in County Meath, 1723 into a family already saturated with sons. When still a child, his family relocated to Spain where Alexander was educated at the Colegio de Padres de las Escuelas Pías in Saragosa. At the incredibly young age of 11, he joined the ranks of an Irish wing of the Spanish army, the Regiment of Hibernia - serving mainly in Catalonia initially.

Hibernia Regiment: Known by many in Spain as "O'Neill's Regiment", it was formed in 1710 from some of the many Irishmen who fled their own country in the wake of the Flight of the Earls and the penal laws and who became known as the Wild Geese a name which has become synonymous in modern times for Irish soldiers throughout the world.

From early in his career, his ascendance up the ladder of promotions with the army was awe-inspiring. By 17 he was a sub-lieutenant, and within a year promoted to full Lieutenant - this came following his time fighting with his regiment in Italy during the Austrian War of Succession, 1740-48.

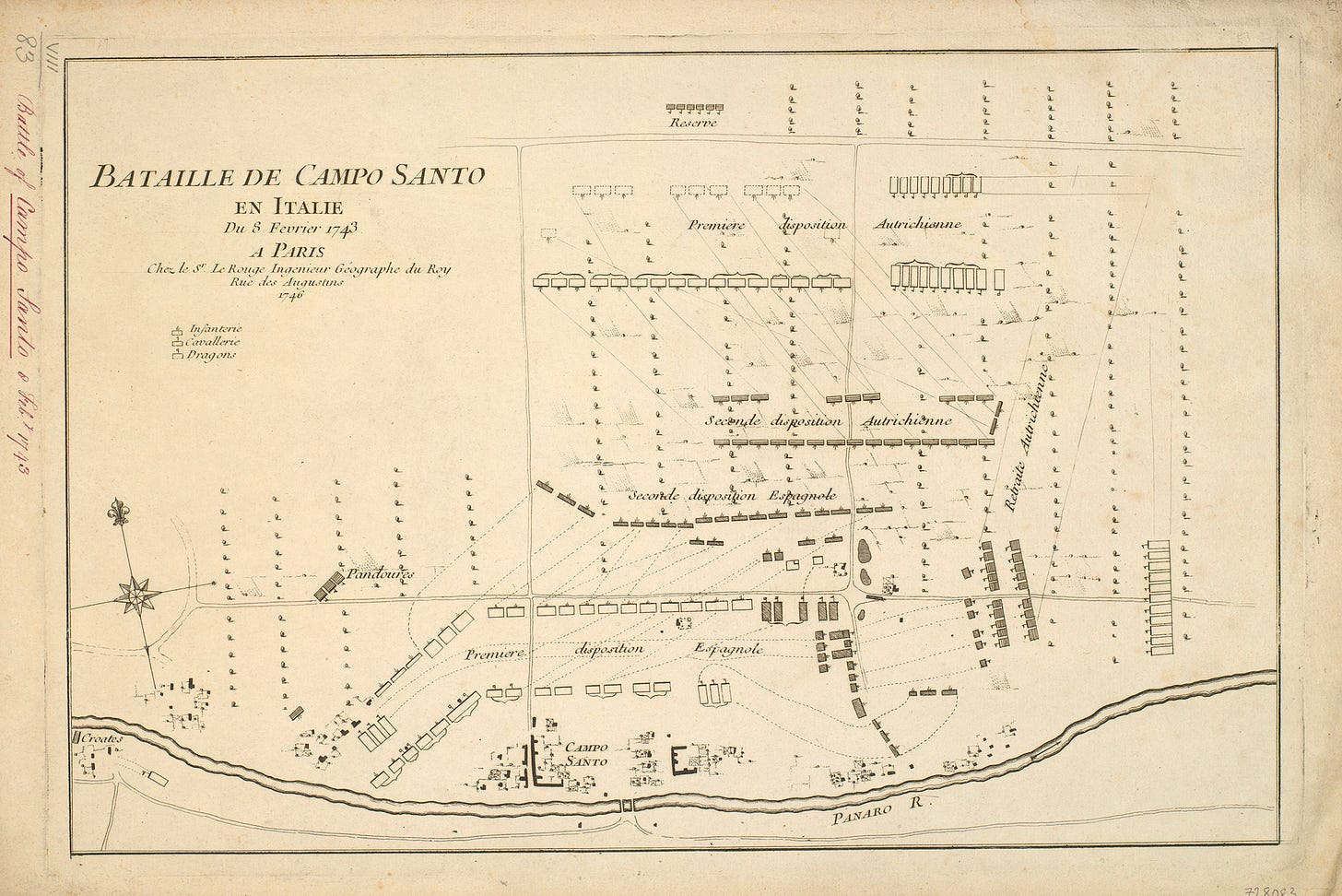

During this campaign, at the Battle of Campo Santo, 1743, O’Reilly was injured after taking a musket ball to his leg (an injury which left him with a trademark limp for the rest of his life). After both armies retreated from the battlefield, O’Reilly was left on the field of battle amidst his dead and dying comrades. When the morning rolled around, he was about to be finished off by an Austrian bayonet, but he managed to defray the killing blow by claiming to be of a wealthy Spanish family, and worth his weight in gold if ransomed.

Whether it be charm, charisma or pure greed on the part of the Austrian - O’Reilly was spared and brought to the Austrian commander, who just by happenstance, was also an Irishman named Browne. Browne, understanding the false reality to O’Reilly’s gambit couldn’t help but admire the bravura of the entire thing and agreed to send him back to the Spanish ranks as part of a prisoner exchange and had Austrian medics tend to his injuries.

By the end of the war in 1748, he was promoted to 3rd in command of the Hibernia Regiment but he quickly grew bored of daily regimental life in peace time. As soon as an opportunity arose to return to a war setting, he sought to leave Spain to volunteer to serve with the Austrian army during the Third Silesian War with Prussia in 1757. The Prussian army under King Frederick the Great had become renowned for its advanced tactics for maneuver and attack. O’Reilly wanted to observe the Prussians in action so that he might return to Spain with these innovations and reforms, and implement them to the Hibernia Regiment.

He wrote of the Prussians;

‘Their Brandenburgers and Pomeranians are the best soldiers in Germany. These men are tall, solid, hardened by work, properly trained as soldiers from the cradle, with a discipline in every sphere that is superior to that of every other army; the skill, fearlessness and perseverance of their monarch, and the impression he makes on their morale, are advantages that are difficult to overcome’.

By the close of the 1750s, the Third Silesian War had become engrossed in the global conflict that became known as the Seven Years War. This conflagration brought Spain into conflict with Britain and Portugal, necessitating O’Reilly’s return to Spain. In his new positions as Colonel and later Brigadier-General (he received both promotions in 1759), he managed to reform his infantry units in the Prussian style before they engaged in combat. When in 1761, Spain invaded Northern Portugal O’Reilly was able to put his reforms on full display and proved their utility in a successful attack against British and Portuguese forces, confirming their superiority.

Caribbean Reformer

By 1763 he was again promoted, this time to Major-General, and that same year sent to Cuba to oversee renovation of the islands defenses. He was requested by the new Cuban Governor Ambrosio de Funes Villalpando, Count of Ricla to accompany him as field marshal. With great gusto, O’Reilly set about creating detailed plans of action and personally selected the officers to accompany him. When they arrived in Havana, they found it a ruin - dockyard destroyed, houses and shops damaged and every wooden structure had been burned to the ground.

His main objective was to try and understand why and how the town fell to the British so easily during the Seven Years War, and to design and implement improvements to prevent it happening again. He set about inspecting fortifications and the state of the local army and militias with lengthy interviews which became a tedious task;

‘They all bring with them a sealed written statement which I am obliged to read and which actually tells me nothing; it seems more like a brigade of clerks rather than soldiers’.

O’Reilly set about surveying the entire Island, all of its ports and much of its agricultural territories. As the governor had fallen ill during this time, most of the work and responsibility was at the feet of O’Reilly and his reports were nothing short of thorough and meticulous. He recommended a new justice system, increased agricultural production and increased beef production with the introduction of markets and auctions to improve quality. He even recommended the introduction of thousands of Irish farmers to bring their industriousness to the island agricultural sector to boost profits!

His biggest roadblock came when he tried to reform and overhaul the fortifications on the island. Silvestre Aborca, the Director of Fortifications, shared a similar, steadfast, and stubborn mindset as O’Reilly, so the two inevitably clashed. He felt it was his responsibility and duty to be in charge of the redevelopment. In Response O’Reilly stated: ‘According to his pretensions, it is like choosing our naval commanders from ship builders’.

Governor Ricala heaped so much praise upon O’Reilly and everything he accomplished, that instead of returning to Spain and his role in the army, the King appointed him Governor of Puerto Rico in 1765, tasked with much the same challenges as Cuba - he reorganized the islands defences and military structure. In both islands, the key changes to military structure were shorter rotations for garrison regiments. A garrison could spend no more than two years on either island - this was in an effort to reduce complacency and risk of corruption. The militias were overhauled and trained in a new manner, provided with new uniforms and the appointments of officers were confirmed with certificates provided by O’Reilly but signed by the King himself, instilling a greater sense of duty on those chosen.

O’Reilly returned to Spain in 1766 and was appointed Inspector General of Spanish Infantry with instructions to introduce Prussian drill and tactics to all regiments in the Spanish army. He was fast approaching the pinnacle of his life, and had earned a reputation as the leading infantry tactician in the Spanish army. His aura was of immense scale, leading efforts across the Spanish empire to improve military tactics, reforms, fortifications - all of which brought him into the immediate orbit and patronage of the King. The event which would come to define him and his career for better or worse, was yet to come though.

‘Bloody’ O’Reilly?

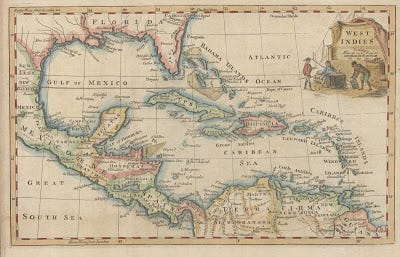

In 1768, following the transfer of Louisiana Territory from the French to Spanish hands following the Seven Years War the first Spanish Governor of the territory, Antonio de Ulloa, with too few soldiers was expelled by a revolt led by mostly French settlers in the region.

Under orders given to him personally from the King, O’Reilly was tasked with travelling to New Orleans under a force of 2,000 soldiers and re-establish Spanish control over the region. He was essentially given unchecked power from the Spanish monarch, granted permission to use any means to achieve his goals:

‘Trusting in your ability and notorious zeal for my royal service, I have destine you to depart for America…to take formal possession of Louisiana…to organise legal proceedings and to chastise, conforming with the law, the exciters and associates of the insurrection…you shall establish military as well as political administrations of justice. I entrust you with extensive and full power and authority…and if necessary, use of force’.

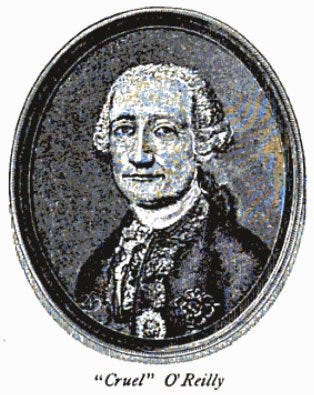

It is this Louisiana Expedition that O’Reilly is probably most recognized for. It earned him the moniker ‘Bloody O’Reilly’ which is still used today in New Orleans. Arriving in the summer of 1769, O’Reilly’s arrival was superbly stage managed to achieve maximum impact. The terrified local populace stood in silence, while the Spanish forces marched from port to the town centre. Upper most in their minds was the reputation that the Spanish had gained for revenge and soon all thoughts of rebellion had dissipated.

Spanish law was re-established in the territory and the five leaders of the revolt were tried while the rest of the population was granted a general pardon from the King. The five ringleaders were sentenced to death. Those considered accomplices received prison terms, not death. Only those, without whom the insurrection would not have occurred, were executed.

The name Bloody O’Reilly, descends from those offended in Louisiana and the French Government in the 18th century, and was promulgated for nearly two centuries with little fact-finding done to understand it. It is more understood today that he was not the blood thirsty anti-French demagogue he had been painted as for so long. Instead he was a meticulous and fair statesmen who was following Spanish law to the letter. The Historic New Orleans Collection today recognizes that the name is likely un-earned, and that O’Reilly, as far as 18th century governors and statesmen go, was far from ‘Bloody’.

He set about doing to Louisiana, what he did during previous postings to the Caribbean. He instituted political, civil and judicial reforms to remold the colony and New Orleans in a Spanish image of civility. He reorganized the city’s defenses and established new treaty’s with Native Americans to the north, he decommissioned unnecessary fortifications, introduced price controls on staple goods and he overhauled the city council with members he picked himself - he made sure that most if not all were of French origin to appease local sympathies.

King Carlos III had chosen him to subdue a rebellion, punish its organizers, and install an orderly government in Louisiana. In just six months he accomplished all three, leaving Louisiana a set of laws and institutions that served the colony well until its return to French control under Napoleon three decades later.

Peak and Decline

Upon his return to Spain in the winter of 1769-70, O'Reilly was made Military Governor of Madrid, giving him control of all civil and criminal administration. One English traveler spoke of his distaste to the ‘Famous O’Reilly’: ‘the powers at his disposal mean that he is surround by flatterers, but his despotic character makes him hated and despised by the people’. Though from further correspondence of the same individual, it appears O’Reilly may have found him easy to frustrate and rather gullible, resulting in a fair amount of teasing.

Also during this time, he had returned to his post as Inspector General for Infantry in the Spanish Army but was also appointed Inspector-General of the Spanish Army of America introducing various reforms across the Spanish Empire and its colonies. Carlos III, in recognition of his reforms over the previous decade and his role in quelling the New Orleans revolt in 1769, named him Condé de O’Reilly and Viscondé de Cavan. His reputation at court as Spain’s foremost infantry commander was at its height.

Once a pinnacle is reached, there must inevitably be a fall. This came in the form of an abortive expedition to Algeria in 1775 led by O’Reilly. He was sent to the North African coast to combat pirates who were attacking Spanish shipping in the Mediterranean. With the command of 22,000 men, he was to make a severe show of force to quell pirate activity and stabilise the shipping lanes. Whether from an inflated sense of self, bad weather, poor planning or simply a superior enemy - the end result was a national disaster for Spain and a personal one for O’Reilly.

He lost anywhere from 1-4,000 solders, nearly 25% of his force and he admitted sole responsibility. He was exiled to the Chafarinas Islands off the coast of North Africa, a real fall from grace in the eyes of the Spanish public. It led to significant public outrage which was directed at ‘foreigners’ in high government offices controlling the destiny of Spain.

His influence at court and with the king however became very apparent as he was recalled from his exile within a year and asked to serve as Captain General of Andalucía in 1776 and Cadiz in 1780 - serving out both postings until 1786. At Cadiz he was influential in organising the supply convoys which served the Spanish armies in America and renovated the ancient roman aqueduct to improve the towns water supplies. He went from being one of the empires most popular and effective military advisors, to becoming what was essentially a local administrator.

From 1786 he entered into a life of semi retirement having reached the age of 64, having lived a life of opulence and grandeur, of immense fame and importance - but now one of moderate adulation after Algiers. The Spanish government made one final request of his military mind in 1794 when war broke out between Spain and Revolutionary France

He was asked to take command of the naval base at Tolouse, then under control of Royalist forces besieged by the revolutionary armies of France. Before he could make it, the port fell to forces led by Napoleon Bonaparte, and instead he was to lead the defence of the Eastern Pyrennes which straddled the border of France and Spain.

Again, he was simply not destined to take up his final command - Alexander O’Reilly suffered a stroke enroute and died on 23rd March 1794. He is buried where he passed at the parish church of Bonete in Murcia where a plaque on his grave commemorates his long and distinguished service for the Spanish Crown. He is but one of many Irish individuals who found fame and success in foreign armies and empires during the 18th century, there are generals, governors and Prime Ministers out there to be discussed, so stay tuned!

Help Ireland and the Age of Revolution grow!

This newsletter is and always will be free to access, enjoy and engage with, but it does take time and effort to create alongside my usual work routine. If you enjoy what I do here and want to see it become even better, please do consider chipping in!

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

Allan J. Kuethe, ‘The Development of the Cuban Military as a Sociopolitical Elite, 1763-83’ in Hispanic American Historical Review (1981) 61 (4): 695–704, online at: https://read.dukeupress.edu/hahr/article/61/4/695/149385/The-Development-of-the-Cuban-Military-as-a

Cecilia Hock, ‘How “Bloody” was O’Reilly?’ and exhibition curated by the Historic New Orleans Collection, 2022, online at: https://hnoc.org/publishing/first-draft/how-bloody-was-oreilly-revisiting-controversial-governors-legacy.

Tim Fanning, Paisanos - Chapter 3: New Model Army (2017).

Samuel Fannin, Alexander “Bloody” O’Reilly in History Ireland (2001), vol. 9, no.3, online at: https://historyireland.com/alexander-bloody-oreilly/

David Murphy, ‘O'Reilly, Count Alexander’ in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, online at: https://www.dib.ie/biography/oreilly-count-alexander-a6980

A great read and someone who should be better known . I curious as to why the family left and went to Spain ?

Great read thanks.