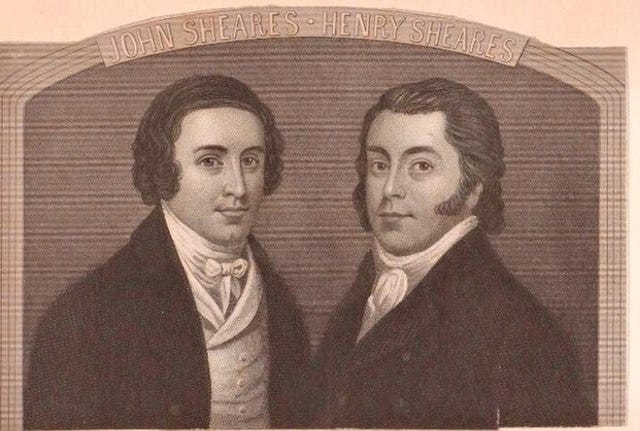

**It has come to my knowledge that this anecdote is exactly that. Daniel O’Connells biographer created this story to reinforce O’Connells dislike of the 1798 rebels, the Sheares and what they stood for. The Sheares brothers may have been on the packet ship, but they left Paris 3 days before the execution of the King**

Monday 21st January 1793 was a day of gloom which descended upon Europe. The winds of revolution in France shifted dramatically in a way not felt since the English Civil War of the 1640s. Two years of revolution had continued in France with varying degrees of success but the one thing which remained contentious and undecided amongst different political groups - what to do with the monarchy.

Initially reform groups in Ireland welcomed events in France believing it to be the end of absolutist rule in favour of a constitutional monarchy akin to Great Britain and Ireland. The French royal family however had shown themselves to be unwilling participants and had been found to be in concert with émigré forces to not only try and flee, but to subvert the established political rule. In late 1792 the decision was made by the National Assembly to put the king on trial for treason. He was found guilty and sentenced to death by a single vote.

On 21st January 1793, King Louis was paraded to the Place de la Révolution, modern day Concorde. He was accompanied by an Irish born priest, who kept him company throughout the night and read the former king his last rites. I have previously discussed the role of Abbé Edgeworth in length - his memoirs providing valuable insight in the kings final hours. For any new readers I highly recommend checking it out here or click the image below!

Abbé Edgeworth was not the only Irish person to be impacted by the events of 21st January however. Henry and John Sheares, Dublin lawyers, who revelled in reading about the revolution from 1789 had been visiting family in Paris. While there, they took their chance to become acquainted with revolutionary thinkers, and attended banquets such as that of White’s Hotel. They were also present for the execution of the King on 21st January and made sure to have a souvenir to mark it.

Upon returning to Dublin both brothers became members of the Society of United Irishmen in Spring 1793 – John often chairing public meetings. The two would become central leaders of the society prior to the 1798 Rebellion. On 21st May 1798, on the eve of the outbreak of hostilities both brothers were arrested for their role in inciting an insurrection after a government informant earned their confidence and was invited to their house. Both were found guilty of treason and executed as a result.

But let us return, to the souvenir I mentioned previously. Not only did they revel in revolutionary fervour, and subsequently import such fervour to Ireland with great enthusiasm. They revelled in the death of the king - and to prove it they ensured they got a handkerchief soaked in the blood of Louis XVI. They were far from shy about their exploits, showing and telling to all who would listen on the packet ship across the English Channel. And by sheer happenstance, who happened to be sitting across from them, or even maybe sharing the same bench? Another set of brothers, much younger, and of another political persuasion entirely - Daniel O’Connell and his brother Maurice.

Daniel O’Connell is a monumental figure of Irish history from this period. He is known as the man who ushered in Catholic Emancipation in the 1820s by running for election. At this time Catholics had the right to vote and run in elections, but they could not take up their seat in Westminster if successful. This was because of the Oath of Supremacy each MP had to make upon taking his seat in parliament. The Oath - the requirement that MPs acknowledge the King as ‘Supreme Governor’ of the Church - forced Catholics to renounce their faith and the Pope as head of the Church.

O’Connell contested an seat in a by-election in Clare in 1828. This brought into sharp focus the issue of Catholic Emancipation which prompted the then Prime Minister, The Duke of Wellington to say:

‘This state of things cannot be allowed to continue … Something must be done.’

The result? A concerted effort from Wellington, another Irish born politician and military figure - to usher in Catholic Emancipation fully. He did so in the face of stern opposition from his own parliamentary supporters and the monarchy. Keep an eye out for future posts highlighting the career of Wellington further.

In 1793 however, O'Connell was but a teenager, at the beginning of his life. He and his brother were sent to France in 1791 to complete their education at the Jesuit College in Douai in Northern France near the modern day Belgian border. He was far from being the towering figure we come to know. He however credits his shared voyage with the Sheares’ as formative to his political beliefs.

O’Connell later in life was a politician who held the ‘mob’* in contempt and viewed, as the only moral path, the political one eschewing violence as the least affective method of ushering in change. He drew ire from surviving United Irishmen many years later for comments he made in relation to the 1798 Rebellion, perhaps the bloodiest conflict of Irelands long history. In May 1841 he stated:

‘As to 1798, we leave the weak and wicked men who considered sanguinary violence as part of their resources for ameliorating our institutions, and the equally wicked and villainously designing wretches who fomented the rebellion, and made it explode in order that in the defeat of the rebellious attempt, they might be able to extinguish the liberties of Ireland. We leave both these classes of miscreants to the contempt and indignation of mankind…’

This debate of morality, of violence versus peaceful protest was to push wedge between O’Connell, surviving rebels of 1798 and the Young Ireland movement in the 1840s. On that packet ship from Calais to England, worlds unknowingly collided. Two sets of brothers from two dramatically different eras of Irish history combined, one unwittingly impacting the other.

While the Sheares’ flaunted their blood soaked handkerchief from the kings execution, O’Connell committed to a life in which the ‘mob’ should be feared and violence should never be a means to an end. When Daniel and Maurice arrived at Calais they breathed a sigh of relieve and removed their tri-coloured cockades - tossing them into the sea. They had been berated by crowds on the way to Calais for being ‘young priests’ and ‘little aristocrats’ leaving them with a particularly sour taste of revolutionary frenzy.

It was made clear to O’Connell that the boat was filled with many Englishmen deemed aristocratic and viewed the political climate too hostile for comfort. By the time they boarded ship the news of the Kings execution had filled Calais with equal measure excitement and terror. As Patrick M. Geoghegan points out - when the Sheares’ were pressed on how they could watch such a spectacle as the execution of a king, they simply replied in a way which made O’Connell shudder, ‘From love of the cause!’ The experience of both revolutionary France and limited proximity to the Sheares brothers deeply impacted O’Connell, leaving him convinced that;

‘the altar of liberty totters when it is cemented only with blood, when it is supported only with carcases’.

The political world of the Sheares’ and O’Connell share little in common. They are diametrically opposed in both the composition of politics in Ireland and also the approach which people took to it in general. The late eighteenth century witnessed the rise of Irish Nationalism and Republicanism - in the form first of a Protestant Ascendancy parliament with legislative independence, and later attempts by the United Irishmen to force a separation of Ireland and Britain. The world of O’Connell, was one of Union - gone was the Dublin parliament and in its place were 100 seats in Westminster.

The rebellion of 1798 had left a bad taste in the mouths of many and as I have spoken of before, it was incredibly violent. It is not considered often enough just how damaging the rebellion was to Ireland. More people were killed in a short few months than in the 1916 Rising, the War of Independence and the Civil War combined. It deeply impacted the way O’Connell approached politics, as it did many politicians who came out the other side - be they Nationalists, Unionists or other.

*The word ‘mob’ is a very derogative word, used purely in its context. It is a word used for the public whom expressed their agency at a time when public officials deemed them inferior.

If you like my work and want to say thanks, or support me in another way, you can buy me a coffee! Nothing is expected, but any support is greatly appreciated! https://www.buymeacoffee.com/ruairiaor

Further Reading:

Oliver MacDonagh, O'Connell: The Life of Daniel O'Connell (London, 1991).

Patrick M. Geoghegan, King Dan: the Rise of Daniel O’Connell, 1775-1829 (Dublin, 2008).

Nancy J. Curtin, The United Irishmen (1994)

Hi Ruairí. I just found out this piece on the famous anecdote about the Sheares.

I have to tell: this anecdote, which comes from Daniel O'Connell's biographer, is false and was invented by him in order to complete the portait of O'Connell as opposed to the United Irishmen and especially the Sheares, whose trial and execution, on the 14 July of 1798 implemented a memory of massacrers and traitors.

The Sheares had left Paris three days before the execution!

Mathieu

Very interesting, as always, Ruairi.