The year was 1793, and the French Revolution had begun to spiral into bouts of radicalisation and increased violence. By the close of 1792 arguments began to be made that the existence of the monarchy was in and of itself a crime against France and that the monarchy attempts to court other European states for help was treason. It is in this context that we are introduced to Henry Essex, better known as Abbé Edgeworth (1745-1807).

Edgeworth came to France at a young age when his father was forced to emigrate as a result of strict penal laws targeting Catholics. As a result of these laws, the training of Catholics was outlawed in Ireland – it is at this point we see the importance of the Irish Colleges abroad, mainly those in France, come into play.

It is in this system of European colleges that we see the life of Edgeworth develop, it is a realm in which he comes to accrue a great deal of recognition. He received a great education during his time in France and worked his way to prominence in the Irish Catholic Hierarchy. The Abbé fell into the orbit of the French Royal family in 1791 to become confessor to Princess Elizabeth (1764-94), sister to the King. The two would develop a close friendship and it is this relationship which led to the Abbé becoming the confessor of Louis XVI.

On January 20th, a vote passed the legislative assembly in Paris condemning the King to death – the vote passed 361 in favour of immediate execution, 360 against, his fate was decided by a single vote. It is on the eve of Louis’ execution that Edgeworth is requested by Louis to be his final confessor – an honour which the Abbé feels a great deal of worry over, but in no position to refuse. The story presented here today is taken from the Abbé’s memoirs – all quotations are exactly as they are in the document, highlighting how impactful this document is in presenting the King in his final hours.

The Abbé found himself not just humbled by the request but similarly astonished at the nature to which his majesty had made such a request, he had left the choice entirely up to him and hoped that Edgeworth would not refuse him. Any man would have felt himself inclined to comply with such a message, Edgeworth felt it as a command that could not be disobeyed and ventured forth to Temple Prison to be introduced to the King on the evening of January 20th, 1793.

The journey to the Temple was a silent one, though attempts were made by Dominique Garat (1749-1833), Minister for Justice to break it: ‘Great God, with what a dreadful commission am I charged! What resignation! What courage! No, human nature alone could not give such fortitude; he possesses something beyond it’. Fearing he may speak too earnestly against the revolution, Edgeworth remained silent – understanding his priority was that of the King and ensuring he could provide him of religious services.

Edgeworth was asked to wait, after being searched on two occasions, and passing through a great series of guards while representatives of the Commune accompanied the minister to speak with the King. He was eventually requested to follow and entered to members of the Commune reading the fatal decree, which sentenced Louis XVI to death the following day.

The King remained calm, tranquil and unmoved – at the sight of Edgeworth he waved everyone away and they obeyed in silence, and Edgeworth found himself alone with his sovereign. Having composed himself for so long, the Abbé found himself no longer master to his own emotions, fell to his knees and began to cry. The King answered his tears only by his own and resolutely said:

‘Forgive me, sir, a moment’s weakness, if such it can be called; for a long time I have lived among my enemies, and habit has in some degree familiarised me to them; but when I behold a faithful subject, this is to me a new sight, a different language reaches my heart, and in spite of my utmost efforts, I am melted’.

The King saw fit to read aloud his final will and testament, Edgeworth was in awe of Louis’ composure who not only read it once but twice. At no point did he falter or adjust his tone except in circumstances where he spoke the name of those most dear to him – ‘then all his tenderness was awakened, he was obliged to pause a moment, and his tears flowed notwithstanding his efforts to restrain them’. Shortly after, the King was permitted a short time with his family in order to say goodbye before he passed on to eternity. ‘Not only tears were shed, and sobs were heard, but piercing cries’.

The King and Edgeworth made the decision to try and rest before the morning came. They rose at 5am and commenced the final mass. Between 7am and 8am, many visitors came to the Louis’ chambers to simply ensure that he remained not only present but also alive – something which the king found absurdly amusing.

‘These people see daggers and poison everywhere; they fear that I shall destroy myself…Alas they little know me! To kill myself would indeed be weakness’.

At 8 o’clock on the morning of January 21st, Antoine Joseph Santerre (1752-1809), chief of the National Guard informed the King that it was time to go. Louis had anticipated that the Abbé would quit his task once they had left the Temple but was astonished to see him forgo his own safety and accompany him to the scaffold.

The streets of Paris were so crowded with protesters calling for the Kings head, armed with pikes and guns that it took two hours to reach the place of execution, previously called the Place Louis XV and now the Place de la Concorde. Upon arrival, the King simply stated, ‘We are arrived, If I mistake not’.

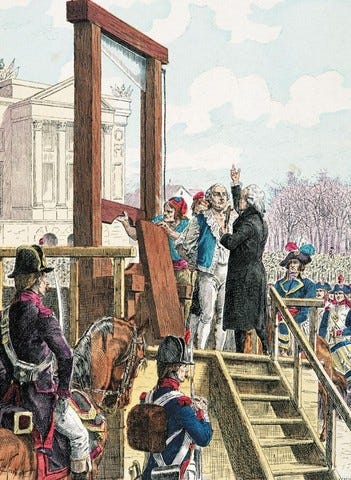

When the executioners attempted to seize the King, bind his arms and cut his hair, he resisted, ‘do what you have been ordered, but you shall never bind me’. Louis looked to Edgeworth for guidance and seeing that the situation was hopeless he advised the King that his submission simply brings him closer to Christ in that he is suffering the same humilities as the son of God.

The path leading to the scaffold was steep and difficult, Louis lent on the Abbé’s arms and continued to walk confidently across the scaffold in absolute silence. In his address to the crowd, Louis cried:

‘I die innocent of all the crimes laid to my charge; I pardon those who have occasioned my death; and I pray to god that the blood you are about to shed will not be visited upon France!’.

He would have continued but Santerre sought to cut him off, drawing his sword, signaling the drums to roll. Within an instant, the King was placed on the block and his head separated from his body.

The final words of the Abbé as he stood on the scaffold are contested by the man himself – he is reported to have cried out ‘Fils de St Louis, Montez au ciel! / Son of St Louis, ascend to heaven!’. When asked about this, Edgeworth could neither confirm nor deny if it was true as the moment in his memory is of such a blur from the moment the King had died. He had though, become acutely aware that he was now alone and feared he was next for the guillotine.

When the executioner showed the bleeding head to the mob, Edgeworth ‘indeed though it time to quit the scaffold; but casting my eyes around, I saw myself invested by 20 or 30,000 men at arms…all eyes upon me’. Upon reaching the crowd though, he met no resistance, believing that because he was wearing civilian clothes, nobody had cause to believe he was a priest, let alone the Kings confessor. Alas, a policy demanding priests abandon their clerical vestments, may have saved the life of a man devoutly against the revolution.

France remained hazardous all the same for Edgeworth, he received parting advice from Malesherbes:

‘Fly, my dear sir, from this land of tigers that are now let loose in it…it is not Paris alone, but France itself you must leave. For you I do not see a safe place in it’.

Edgeworth would remain in France for the next three years, evading arrest and hiding away. He would eventually leave to re-join the now exiled royal family, spending much time in Germany and Russia. He would later die in Mittau, Russia (now in Latvia) while ministering for French prisoners of war. He would be cared for in his dying days by the daughter of Louis XVI, further highlighting the relationship he had with the family and how much they cared for him. He died there on 22 May 1807.

Further Reading:

Liam Swords, The Green Cockade: the Irish in the French Revolution 1789-1815 (Dublin, 1989).

C. Sneyd Edgeworth, Memoirs of the Abbé Edgeworth; containing his narrative of the last hours of Louis XVI (London, 1815), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000564908.

Interesting. I'll be writing a bit about Ireland in 2024 and 2025, so your newsletter will be very interesting and helpful to me. Look forward to reading more.